A warning to readers: This story contains cursing and references to suicide and sexual violence.

It all starts with an argument on a bike path: a nanny and the three kids she’s watching versus an angry man in his backyard. And a cellphone camera that starts rolling just after the man curses at them.

Erin McDermott and the kids, who are 3, 6 and 7, are on a neighborhood path in suburban Nashville that happens to run behind the man’s home. They’ve parked their bikes to eat some graham crackers and look for fossils.

But the man thinks they’ve overstayed their welcome. It’s April 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, and Tennessee is under a Safer at Home order. He wants them to get away from his property.

The man paces back and forth in a baggy, long-sleeve T-shirt and gym shorts. He says he’ll swear at the kids all day if they don’t leave

“Children, do you want to stay and listen to me f****** cuss all day?” the man shouts, waving his arms in the air.

“Stop saying curse words!” one of the kids yells back.

“Say it! Say it with me!” the man insists. “Oh, s***.”

McDermott says she’s going to call the cops and tell them where the man lives if he doesn’t stop. But he doesn’t seem worried at all about getting law enforcement involved in this petty dispute.

“I want you to call the police,” he says, almost daring her.

“He just was so agitated and so aggressive,” McDermott said later in an interview. “Even the way that he was talking to the kids, I mean, like, ‘Throw rocks at me, cuss with me,’ like, who — no rational person does that.”

McDermott didn’t want the man to get away with such bad behavior. So, she decided to publish the video online.

“I had no idea who he was,” McDermott said.

A local gossip site identified the man as a captain at the Metro Nashville Police Department. It shared the video, and the clip quickly went viral.

“Then I found out it was a police officer,” McDermott said. “And then I got really scared.”

Erin McDermott thought she was just posting a video of an angry man in his backyard. But her recording put a cop in the spotlight. It cracked a hole in the blue wall that protects some police accused of bad behavior. It sparked a #MeToo moment within the Metro Nashville Police Department. And it inspired officers who had long kept quiet about misconduct to finally speak up.

For years, many MNPD employees had been holding back a secret. Behind the department’s blue wall, these people said, a toxic culture of misconduct and retaliation had scared many into silence. And the disciplinary system that was supposed to hold police accountable, they said, had allowed that culture to thrive.

Shootings and killings by police have filled the headlines in recent years. But this is not the same story about policing you’ve read before. This is a story about how police treat their own. And what it means for the community when officers victimize their fellow men and women in blue.

A toxic culture

In the past year, WPLN News and APM Reports have reviewed thousands of pages of public records and a decade’s worth of disciplinary data. Reporters have also interviewed more than 20 current and former MNPD employees, who have described a chilling pattern. They say the department often protects police accused of bad behavior, if they’re in good graces with the top brass. But those who challenge the status quo, they say, are ostracized, punished more severely or forced out — especially women and people of color.

“If you’re not really drinking the Kool-Aid and stuff like that, you’re not gonna move far unless you just keep your head down,” said Eric Harvey, a former officer who said he quickly gave up any hope of getting promoted out of patrol because he often disagreed with his supervisors.

More: How We Reported WPLN News Investigates: Behind the Blue Wall

In a department that is 75% male and 77% white (that’s including both sworn and civilian staff — officers alone skew even whiter and more male), current and former employees said there’s little room for complaints or differences of opinion.

“I’ve been shunned. I’ve been pushed aside, or whatever,” said former Captain Dhana Jones, the lone Black woman in the upper ranks for years, until she retired in 2020. “I mean, to me, it’s really, really toxic.”

A new police chief has pledged to diversify the force and recruit officers who can better relate to the communities they serve. But, for years, the few who do think differently say they have often been pushed to the sidelines. Those who rock the boat, they say, are often disciplined, passed over for assignments or forced to leave the department altogether.

“I had to resign. I had to resign,” said Gilbert Ramirez, a former officer who left the department after he was decommissioned for a policy violation he denied, then had his sexuality outed in a press release without his permission. “It kills me, because it’s not right what they did to me.”

But when some officers are accused of serious misconduct, they manage to get by with little or no discipline. Sometimes they’re even promoted. Many current and former employees say it largely depends on whether you’re in good favor with the leaders of the department and the Office of Professional Accountability.

“I mean, it was obvious that some got away with whatever, with little taps on the wrist, and then others, they were like beating them down,” said former Sergeant Marita Granberry, who worked at the department for about 30 years before retiring in 2015. “It’s like the rules were only applied to certain people, and other people could do whatever they wanted to do and squeeze out of it.”

And these anecdotes are backed up in data and records.

WPLN News and APM Reports have reviewed more than a dozen lawsuits and internal complaints from employees who say they’ve faced discrimination. We have also obtained thousands of pages of personnel files and 10 years of demographic and disciplinary data from MNPD.

More: Browse through some of the records and data we reviewed for this investigation.

The data show that minority employees accused of wrongdoing faced higher rates of severe discipline — suspension, demotion and/or termination — than their white colleagues. While one in five disciplinary investigations into white employees ended in severe punishments, nearly one in four investigations into Latino employees and about one in three of those into Black employees did.

And the gap was particularly large for Black women. Black female employees who were investigated for policy violations were suspended, demoted and/or terminated at more than twice the rate of white employees — 41% compared to 20%.

Even when WPLN News and APM Reports looked at the outcomes of disciplinary investigations for comparable infractions, non-white employees still faced severe discipline at higher rates than white ones.

MNPD would not make Chief John Drake available for an interview, and he did not respond to detailed questions. Drake’s spokesperson said in an email he could not answer for decisions made by his predecessors.

Instead, the department outlined multiple steps the chief has taken to diversify the force and better support female and non-white employees since taking the helm last year. Those include more resources for mothers, improved tracking and review of internal complaints, and a zero-tolerance policy for sexual assault and harassment.

Drake has also asked Deputy Chief Kay Lokey to speak with female employees of the department. Lokey is one of the highest-ranking women at the department. She was also suspended four days in 2016 for mishandling a sexual harassment complaint reported to her by one of her female subordinates.

A captain’s fall from grace

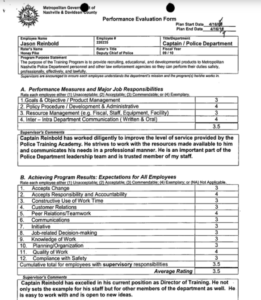

The man from the cellphone video was Captain Jason Reinbold, the leader of the the Metro Nashville Police Department’s Criminal Investigations Division. He had a squeaky-clean disciplinary record and a file full of accolades. Reinbold was one of those cops you would often see in the paper or on the local news.

Reinbold had worked with the police department for more than 25 years when the cellphone video was published. He was a college football recruit turned cop who spent his off hours coaching at a local Catholic school. And he was beloved by many in the upper ranks of the department.

When the city opened a new, multimillion-dollar downtown station in 2014, he was chosen to lead it.

As Reinbold rose through the ranks, his higher ups noted his leadership abilities. They said he was “easy to work with” and that he set an example for the department.

But Reinbold’s esteemed reputation began to unravel in the spring of 2020, after the nanny’s video made the local news. TV stations broadcast beep-filled clips of the captain’s screaming match with McDermott.

The viral cellphone video launched an internal investigation into Reinbold’s actions. A few days after the argument in his backyard, Reinbold was under investigation by the department’s Office of Professional Accountability.

Reinbold had been investigated a few times before, but records show he had never been disciplined.

WPLN News and APM Reports obtained recordings of five investigative interviews with Reinbold through public records requests. They’ve never been shared with the public before.

These recordings provide an unprecedented glimpse into the inner workings of the police department’s disciplinary system and the type of treatment afforded to someone with friends in the upper ranks.

In this case, Reinbold didn’t deny that he’d done something wrong. He sounded embarrassed and remorseful.

Reinbold said he had acted “foolish” and “like an old man at his house.”

“Can I be honest with you for a second?” Reinbold asked the investigator, Ron Carter. “I wish I were in uniform. You know why? I wouldn’t have done it. I wouldn’t have done any of that if I were in uniform.”

“My demeanor would have been completely different,” he said, “because we do it every day, you know?”

But, Carter asked, did the captain have an anger problem?

“If I do have one, I don’t believe it’s not manageable,” Reinbold said. “But I feel that I had a moment in which I flat out tripped and fell on my face with my behavior.”

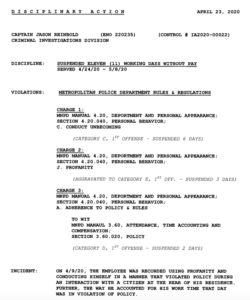

The department spent just over a week investigating the nanny’s complaint against Reinbold. They suspended him 11 working days without pay and transferred him out of the Criminal Investigations Division, where he had supervised the cold case, fraud and sex crimes units.

It was certainly more than a slap on the wrist. But, considering all the negative attention this case had brought the department, it could have been worse. He could have been demoted for setting a bad example as a supervisor.

Reinbold could have even been fired. He originally told Carter he wasn’t working during the argument. But he admitted in a follow-up interview with the investigator that he was technically clocked in at the time.

Untruthfulness at the Nashville police department can be grounds for termination.

But Reinbold kept his rank. Instead of being charged with dishonesty, he was punished for poor time accounting.

“Inconsistency is not necessarily the same as dishonesty,” Kathy Morante, director of the Office of Professional Accountability, wrote in response to emailed questions. The police department did not make her available for an interview.

Morante said employees are charged with dishonesty only when they “knowingly or intentionally” make false statements. In this case, the department decided Reinbold had not tried to be deceitful.

It wasn’t the first time he’d held onto his stripes after facing a serious accusation. It was just the first time it had happened in the public spotlight.

But the aftershocks of Reinbold’s outburst didn’t end there. The argument in his backyard set off a chain of events that exposed a disparity in discipline at MNPD. For some employees investigated for wrongdoing, the consequences can be much more severe.

Choosing Between Justice And Her Job

Monica Blake-Beasley joined the Metro Nashville Police Department in 2005 thinking her job would be, in her words, “all sunshine and rainbows.”

“I was going to go in and fight crime and do the right thing every day,” she said. “I love people, I love working with communities and I wanted to uphold justice.”

Blake-Beasley spent almost 15 years at the Nashville police department as one of the few Black women on the force. And her experience hardly resembled Jason Reinbold’s. But their careers are intertwined.

Blake-Beasley says she began to feel like there was a “different playing field” for women in the department early on. It started back when she was working the midnight shift during her first few months out of the academy.

Late one night, she was patrolling with a field training officer when he met up with a group of officers by Percy Priest Lake on the outskirts of town. She was the only woman.

“And it was uncomfortable just because, you know, again, we’re out at the lake. It’s at night. I don’t know these officers very well,” she said.

Blake-Beasley says two male officers approached her, and one started to make advances. She turned him down. But she says he didn’t want to take “no” for an answer.

“Then they kind of started making jokes. And he said several times, ‘Eatin’ ain’t cheatin,'” Blake-Beasley recalled. “And I was just like, ‘Oh, this is happening right now.’“

Blake-Beasley says the officer kept badgering her until she left.

She felt violated, confused and a little scared.

Blake-Beasley says her field training officer didn’t intervene in the moment and never asked her about it after. So, she figured this was just the type of behavior she was going to have to get used to. And she didn’t report it.

Other women from Blake-Beasley’s academy class told her similar stories about colleagues and supervisors who wanted to sleep with them: fellow officers who made crass jokes, a married supervisor who asked a female rookie to be his “fuck buddy.”

“So, we were all experiencing things,” Blake-Beasley said. “At least the people I talked to, we were all experiencing things in our own ways, not necessarily all the same, but the similar type of incidences.”

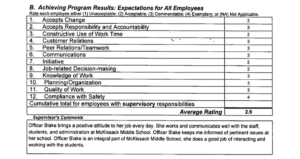

But Blake-Beasley forged on. Like Reinbold, her personnel file shows she received multiple awards and letters of recognition. And when she became a school resource officer, her annual performance evaluations were filled with praise.

“Officer Blake brings a positive attitude to her job every day,” a sergeant wrote in her 2014-2015 review, adding that she worked well with staff, students and administrators. “Officer Blake is an integral part of McKissack Middle School.”

For about a decade, things seemed to be going really well. But then, Blake-Beasley started to notice some things that didn’t quite sit right with her. It felt like she was being treated differently because of her race.

“I first noticed a difference in how we were treated after a card game,” she said.

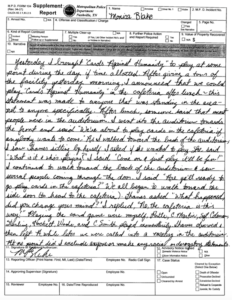

It was the summer of 2014 and Blake-Beasley was working at a summer camp put on by the police department. On a break during a planning week before the campers arrived, Blake-Beasley and a group of officers got caught playing Cards Against Humanity — a raunchy party game known for its dark humor and sexual innuendo.

Eight of the officers playing that day were Black and one was white. Blake-Beasley says the Office of Professional Accountability initially took steps to suspend all of the Black officers, but not the white officer.

Blake-Beasley went back through the surveillance footage and shared it with the Office of Professional Accountability.

“The other African-American officers had said, ‘Monica, do not go tell them, because we’re going to get punished more.’ And I said, ‘No, they want to do the right thing. They just don’t know this. And, you know, we’re not gonna get in trouble for this,'” Blake-Beasley remembers telling them. “That was me being naïve.”

The video showed the white officer playing along with the Black officers. But when Blake-Beasley first brought the investigators the footage, she says they told her they’d never watched it. That they’d just taken the white woman at her word when she said she hadn’t played for long.

Morante says all officers involved were investigated but couldn’t recall the exact order of the investigation.

Everyone ended up getting suspended. But Blake-Beasley got the most suspension days.

MNPD said in a legal memo written at the time that it was because she brought the game to work. But Blake-Beasley thought she was being punished more harshly for questioning the investigation.

She felt dejected and angry. The punishment hurt. But the perceived double standard was even more painful.

“It was heartbreaking,” she said. “I had spent all those years thinking that I was a part of the good guys, thinking that I was part of the Justice League.”

Until then, Blake-Beasley had always given the department the benefit of the doubt. She’d assumed that everyone else was just as committed to fairness as she was. And suddenly, it all felt like an illusion. Blake-Beasley began to lose trust in the system.

“At that point I realized they were only disciplining who they wanted to discipline and that the rules at that point, I felt like, were not the same for me and the other African-American officers as they were for the one Caucasian officer,” she said.

About two years later, something happened to Blake-Beasley that she believes put a target on her back at the department.

On May 2, 2016, Monica Blake-Beasley says she was sexually assaulted by a fellow officer who she had dated on and off for several years. She says he’d been violent with her in the past. And on this particular night, Blake-Beasley says, he strangled her until she passed out. Then he raped her.

More than five years later, it still gives her nightmares. But even as an officer who had been trained to help people who have been sexually assaulted or abused, she was afraid to report it at the time.

“I was terrified to come forward for many different reasons,” she said. “But the number one reason is because I knew that officers just don’t tell on other officers.”

Blake-Beasley says there’s a “blue wall of silence” in law enforcement that teaches police to keep things inside the family. And when you tell on another officer, she says, there’s “hell to pay.” But in a case like this, she didn’t think the unwritten rules should apply to her.

Blake-Beasley had physical marks on her body. She had gone to the doctor.

“It was a horrendous, scary, life-threatening attack,” she said.

Blake-Beasley wanted to think the majority of officers would empathize with her and would want her to be protected, just like they would want for their own loved ones. Even if they couldn’t relate on a personal level, she hoped they would recognize this was exactly the type of emergency police respond to every day.

Blake-Beasley wanted to think her fellow officers would understand why something like this needed to be reported. But she says they didn’t.

“What I discovered was that there was an expectation that my blue trumps the fact that I’m a woman, the fact that I’ve been attacked, the fact that my life had nearly been taken from me with my children in my home,” she said.

“What I learned was that I should have been quiet if I wanted to keep harmony within my job,” Blake-Beasley added. “Never did I think I would have to choose between justice and my job.”

After Blake-Beasley reported the assault, the district attorney charged the officer who she said had attacked her, Julian Pirtle, with rape and aggravated assault. The police department took his gun and badge while it conducted an internal investigation.

But then Blake-Beasley started to feel like she was the one in trouble.

It was a dispute about a supposed policy violation completely unrelated to the assault.

The Office of Professional Accountability launched an investigation into how Blake-Beasley handled an allegation of child abuse at the school where she was stationed. The report came in after her normal shift, when she was supposed to be working a second job, to provide security at a school football game. Investigators had questions about when Blake-Beasley left work that day and when she had notified others about the allegation.

In the course of that investigation, Blake-Beasley told an interviewer she had waited to page other officers because her supervisor had told her to do it while she was in her car. She said her utility belt with all her police gear was in the trunk, where she couldn’t reach it. But later in her interview, Blake-Beasley contradicted herself. She said maybe it was actually in her passenger seat and that perhaps she had waited to send the page for another reason.

That discrepancy was enough for the Office of Professional Accountability to accuse Blake-Beasley of being untruthful, not just inconsistent.

The department ultimately decided Blake-Beasley wasn’t lying. But not before those questions had started circulating about her honesty.

The Office of Professional Accountability told prosecutors and Pirtle’s defense attorney. Morante says the department was required by law to share the information with both sides. Then Pirtle’s lawyer subpoenaed Blake-Beasley’s commander.

Prosecutors decided to drop the rape charge against Pirtle, who had denied the allegations. He resigned from the department and pleaded guilty to aggravated assault. A judge sentenced him to three years of probation, with no jail time.

Blake-Beasley was terrified. And she believed the department had tried to undermine the case. In a lawsuit, she claimed that Pirtle’s best friend, who worked in the Office of Professional Accountability, convinced the unit to investigate her for truthfulness.

“I know what it was like to be victimized by the suspect and then turn around and feel that I was being victimized by the police department, by the defense attorney, by the judge who lowered his bond after he violated the order of protection,” she said. “When you go about everything and do things the right way and those systems that are in place still fail you, it leaves you wondering, ‘Who do you turn to?’ And you end up having to be your own hero.”

When Blake-Beasley accused a fellow officer of rape, she crossed an unspoken line.

In the three years following the assault, the department launched six disciplinary investigations into Blake-Beasley’s behavior. They were all for things that felt silly and arbitrary to her: Picking up her daughter from a dance class before completing an investigation. Recording a testimonial video for a local magician who performed at her kid’s birthday party. Forgetting to file paperwork for a security job at her apartment complex four years earlier.

Each minor infraction she was punished for seemed to her like payback for speaking up. Blake-Beasley says she lost all trust in the system that was supposed to protect good officers and hold the bad ones accountable.

“To find out that we actually had separate groups governed by separate rules, according to who you were and your ability to either grin and bear it or turn a cheek, nothing about that felt like justice to me,” she said.

Morante denies that the investigations were retaliatory, that Blake-Beasley was subject to a double standard or that Pirtle was protected by the department. She also says the department notified prosecutors that Blake-Beasley would be cleared of lying.

“I believe we hold bad officers accountable while also acting to correct the actions of officers who are found to have committed violations,” Morante of the Office of Professional Accountability wrote in an email.

But Blake-Beasley believed she had uncovered a dual disciplinary system at the Nashville police department: one for those who honor the blue wall of silence and another for those who don’t.

“There are tons of policies in place that say: ‘You cannot be discriminatory. You will not be retaliatory,’ ” she said. “But when it comes down to it, the culture of our police department has allowed these things to thrive, and no one has been willing to step up and make them stop. So, I am very grateful that we are now at this juncture where even though they do not want to listen, they are having to listen because it’s no longer — it’s no longer their dirty little secret.”

WPLN and APM Reports’ finding that Black women who have been investigated for misconduct face much higher rates of severe discipline reflect what Blake-Beasley has been saying for years. She was one of the first officers to expose this pattern in court.

In 2018, she filed a lawsuit accusing the police department of multiple civil rights violations. In April 2019, the city of Nashville agreed to settle Blake-Beasley’s suit for $150,000.

Her story got another officer’s attention. One woman decided that if Blake-Beasley had the courage to come forward, she could, too. And, after years of waiting, she decided to report her own claims of sexual misconduct.

‘I can’t go back to policing’

Just a few months after Blake-Beasley’s settlement, a female, former officer lodged a complaint against her captain, Jason Reinbold. Nearly a year before Reinbold made headlines for yelling at a nanny, this woman had accused him of sexual assault. But instead of going to the police department, she shared her story with investigators from the city’s human resources department.

We’re going to call the woman Accuser No. 1, because she’s still afraid of retribution and may be the victim of a sex crime. WPLN News and APM Reports obtained a recording of her interview with investigators.

Less than a minute into her interview with HR, Accuser No. 1 launched into a story she’d shared with only a handful of relatives and colleagues in the past three years. A story that still haunted her. That sent her to the hospital with post-traumatic stress disorder. And that ultimately ended her career.

She said it happened on a quiet day at the office, when the police department was moving out of its old headquarters downtown.

“We were just chit chatting,” Accuser No. 1 said. “And I remember he kept looking — there was a screen that was on the wall, and that screen showed a view of the hallway, where people were coming and going.”

The officer wondered why Reinbold kept looking at the screen. Then, she said, he got up and stood in front of the door.

“He locks the door, and he turns around,” she recalled.

Then, Accuser No. 1 said, Reinbold asked to touch her breast.

“And I was — I was scared,” she said.

Accuser No. 1 didn’t know what to say. She’d never seen a man block the door and lock her in — especially not her own supervisor. So, she blurted out a yes. And then, she said, he groped her left breast.

Accuser No. 1 couldn’t remember exactly what happened next. If she said anything. How she managed to leave. But eventually she did.

“I just walked out, and I just felt humiliated. I felt embarrassed,” Accuser No. 1 told investigators. “I was like, ‘What just happened to me?’ And he’s my captain. What am I supposed to say?”

Accuser No. 1 told HR she wished she’d been strong enough to come forward sooner. But she hadn’t been ready back in 2016. And she hadn’t wanted to destroy Reinbold’s reputation.

Accuser No. 1 didn’t mention it to HR, but in later investigations, she said she and Reinbold had dated for a few months about a decade before the alleged assault. He was six years older and three ranks superior. He was also married.

Reinbold didn’t respond to questions about the affair or Accuser No. 1’s other allegations. But Accuser No. 1 still has a sexually explicit book she says he gave her for Valentine’s Day, signed with a heart. She shared a photo of the inscription with WPLN News and APM Reports. The signature matches Reinbold’s on official paperwork.

“I was so worried about him,” the officer told HR. “How can I tell people that this happened? And what about Jason? He’s married. He’s got kids. What about his career? You know, that’s all, that was the first thing I thought about. It wasn’t me. I wasn’t thinking about me.”

But by the time she filed with HR, Accuser No. 1 had decided to leave the department on a medical pension for PTSD. And she didn’t want to go silently.

“How can I just turn my back and leave the department and not do something?” she said. “Because I was treated wrong. I was treated absolutely wrong, and my career is cut short because of this.”

Accuser No. 1 wanted justice. She said she had to start over, because she didn’t feel comfortable going back to the department — not to the Criminal Investigations Division, not even to patrol.

“I’m done. I can’t go back to policing,” she said. “I don’t feel safe, period.”

After Accuser No. 1 shared her story with the city’s HR department, an investigator confronted Reinbold about the accusation. But when he told Reinbold what Accuser No. 1 had said in her interview, Reinbold denied the allegation. He called it “crazy.”

“It’ll get me upset,” he said. “And I don’t want to get upset.”

Reinbold called the accusation a “shot in the dark.” He tried to connect it to a relationship she’d had in the past with a different supervisor. (During an investigation, Accuser No. 1 denied to the Officer of Professional Accountability that the relationship had been romantic.)

When an HR investigator asked if Reinbold and Accuser No. 1 were friends, he said they had been in the past. But he insisted they’d had virtually no relationship since he’d taken over the Criminal Investigations Division in 2015. The captain said he had supervised many female employees and that he had never had an “inappropriate relationship.”

Reinbold also vehemently denied the assault. But then he took it a step further. He had already noted earlier in the interview that department policy instructs employees to report any harassment or discrimination — including sexual misconduct — whether they are a witness or a victim. When confronted about Accuser No. 1’s sexual assault allegation, Reinbold doubled down.

“If she had experienced something like that, you said, you’re saying the police policy is that she can report to anybody?” the investigator asked.

“She is — not only just could, she’s charged. She should. She shall,” Reinbold insisted. “She is required to report it.”

So, Reinbold had flipped this accusation on its head. He said Accuser No. 1 not only had a chance to report any sexual misconduct to the department. She was required to. But she didn’t.

Reinbold said she could have turned to hundreds of supervisors. Instead, she’d waited nearly three years to bring a complaint.

It was a classic case of “he said, she said.” HR investigators wrote in a fact finding report that they couldn’t prove or disprove anything without evidence. So, they sent their findings back to Reinbold’s supervisor at the police department and said he could decide if he wanted to investigate further.

But no record of an internal investigation appears in Reinbold’s department files. So, when reporters requested his personnel file after cellphone video showed him yelling at a nanny, there was no mention of a sexual misconduct allegation. And the captain never faced any discipline for it.

MNPD noted in an email that the department didn’t take action because HR “did not substantiate any violations.” But that rationale did not prevent other unsubstantiated complaints unrelated to sex from appearing in Reinbold’s file.

So, the only formal complaint of sexual misconduct against Reinbold never went anywhere. It remained hidden, behind the blue wall. That is, until the video put him in the spotlight in the spring of 2020. And a former sex crimes detective didn’t want to keep Accuser No. 1’s allegation a secret any longer.

A #MeToo Moment at the Metro Nashville Police Department

On a hot and sunny day this past June, I met Greta McClain at Centennial Park. It’s a popular gathering space on the west side of town wedged between three hospitals. So, as we talked, people chatted at nearby picnic tables and helicopters whirred overhead.

McClain is an accidental character in this story. She didn’t set out to become the Metro Nashville Police Department’s most vocal critic. But she is the thread that ties all these stories together. Captain Reinbold, the nanny, Blake-Beasley, Accuser No. 1 — they’re all connected to her.

McClain is a sexual assault survivor. She’s a long-time advocate for women’s rights. And she’s a former Nashville police officer who once had deep ties to the department she’s now trying to hold accountable.

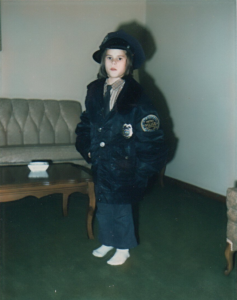

McClain says she became a police officer because she’s “a daddy’s girl.” Her father was a Nashville police officer, and she remembers dressing up in his uniform as little kid.

McClain joined the department in the fall of 1991, after her dad retired. From the beginning, McClain loved her job. And after a few years, she applied to be a sex crimes detective.

McClain had responded to several rape calls on patrol, and she wanted to help more survivors. But she also had a personal reason to join the unit. In college, she says, she was fondled by an employee at the campus recreation center.

McClain thought her own experience with sexual assault would make her a better detective. But sometimes, she says, it didn’t feel like her male colleagues were on the same page.

So, she decided to leave law enforcement and one day transition into full-time advocacy.

Almost two decades later, McClain was raped by a stranger in a parking lot. That incident eventually prompted her to start her own nonprofit to support survivors of sexual assault.

“It was obviously a life-changing, traumatic experience,” she said. “Being a former police officer, I was very hesitant to tell anyone, because I didn’t think that they would believe me. I, myself, didn’t believe that an officer or former officer could be raped. So, I figured, why would anybody else believe me?”

McClainfelt like she should have been able to use her policing skills to stop the man from raping her.

“As a lot of victims do, they blame themselves,” she said. “‘If I had done this, if I had done that.’ And I fell into that same trap.”

McClain kept the assault a secret for several days. She dodged questions about the black eye and bruises on her body. Eventually, she told a few people.

But the former sexual assault detective never reported the incident to police. She was too ashamed. And that guilt started to eat away at her.

Around the end of September 2017, McClain started to seriously contemplate suicide.

“And by mid-October, I was actually one night just like, ‘You know what? I can’t do this anymore,'” she said. “I’d gotten to the point that I was writing my goodbye letters, because I’d decided exactly how I was going to kill myself,” she said.

McClain was going to do it the next day. First, she just needed to write her goodbye letters. But she couldn’t find the words for the last one.

McClain set aside the letter and picked up her phone, desperate for a distraction. As she scrolled through social media, she saw a hashtag that seemed to be popping up all over her feed. Two words. Me too.

The Harvey Weinstein story had just published. Suddenly, celebrities, friends, all sorts of people were sharing their stories of sexual abuse. McClain read through one post after the next. She was shocked.

McClain knew sexual assault was prevalent, but she didn’t realize just how many people had experienced it. And if they had found the courage to keep putting one foot in front of the other day after day, maybe she could, too.

So, McClain stopped writing her last goodbye letter and said to herself: “I’m going to make it to tomorrow.” She repeated it the next day and the next, like a mantra. She would sometimes say it a dozen times a day. It felt like hundreds.

“And I thought, you know what? I can continue to wallow in depression and self-pity, or I can use this trauma to help others and maybe save one other person,” she said.

So, McClain got involved with the local Women’s March. Then she started Silent No Longer. It was very grassroots — just four volunteers, herself included. A vigil here, a workshop there.

The group was struggling to pick up momentum. Until someone she knew shot a viral video.

Erin McDermott, the nanny Reinbold cursed out in his backyard in April 2020, had met the Silent No Longer founder a few years back through the local Women’s March. She thought maybe the organization could help.

After McDermott posted the video of Reinbold, she says messages started to pop up in her inbox. Women from the department who saw her video on YouTube or on the news found her online and started to reach to out.

McDermott was overwhelmed. As she read through the flurry of messages, she felt like she was drinking water from a fire hose. She felt a duty to help the women who had shared their stories with her.

“I mean, to be completely blunt, he screwed with the wrong woman,” she said. “I think that he was so used to that type of behavior and felt that he could get away with it, that he just didn’t think that I would do anything.”

But she was afraid to go up against the department on her own.

So, the nanny reached out to McClain and asked for help. She hoped to put Silent No Longer in touch with the police who told her they’d been mistreated or sexually abused within MNPD.

“This is exactly why we created Silent No Longer,” McClain said. “To speak for those who are afraid to speak for themselves.”

Before long, the phone calls and emails started pouring in. More than 40 current and former employees would eventually share their stories with McClain.

Many accusers had come forward anonymously. But the details they shared were vivid.

One woman said a colleague had chased her around her patrol car and tried to kiss her. Another said male supervisors often stood in the hallway and ranked women’s breasts, lips and butts as they walked past. Some described harassment so intense that it caused sleepless nights, panic attacks and even thoughts of suicide.

The accusers named several leaders of the department in their complaints, and a few said they had been mistreated by Jason Reinbold. The concerns they raised were bigger than just one person. There were many high-ranking and well-connected officers at the department who accusers said were protected from serious consequences, even when the impact on their victims was crippling or career-ending. Meanwhile, those who weren’t part of the so-called “good ol’ boys club,” they said, were punished harshly for minor slip-ups.

Multiple Silent No Longer accusers said it all depended on who your allies were at the department — particularly in the Office of Professional Accountability and the chief’s office.

The nanny video had exposed a secret at the Nashville police department. Officers who had been too afraid to speak up about misconduct by colleagues felt like they couldn’t hold it in any longer.

Abuse of power

About four months after Reinbold yelled at a babysitter in his backyard, Greta McClain held a press conference on Zoom.

McClain told the handful of activists and reporters on the call that she had been approached in April 2020 by a MNPD employee who said she’d been sexually assaulted by Reinbhold. And that the woman claimed to have been retaliated against when she reported the incident.

That woman was Accuser No. 1, the former officer who reported Reinbold to HR in 2019. Others told McClain that Reinbold was one of the “good ol’ boys” at MNPD. They said people faced backlash if they tried to report a member of the group. Or that their complaints were disregarded, if they even found the courage to come forward. Few did.

For many in the department, these revelations weren’t new. But, for years, they’d been hidden from the public eye.

McClain, the former detective, didn’t want to attack law enforcement. She said she was proud to have served as a police officer and that the vast majority of cops do their best to serve with integrity.

“But it’s very difficult to keep the faith and to do what is already a very difficult job when many of those in power abuse that power and use their authority to intimidate those who are truly trying to serve the community honorably,” she said.

Silent No Longer has a case file full of complaints and evidence. The group’s thick three-ring binders contain transcripts of interviews with current and former employees who say they have been mistreated by colleagues and supervisors, a few naming Reinbold. They also include police records, emails and letters from whistleblowers.

There’s no physical proof that any of the allegations against Reinbold are true. These are incidents that often had no witnesses, no video, no police report. Accuser No. 1 is the only person with a documented complaint. And it didn’t go anywhere. She is also the only Reinbold accuser who has agreed to speak with me.

In multiple conversations over the past year, her story has never wavered. And the details she’s shared with me reflect the account she gave to HR in 2019.

The Nashville prosecutor who reviewed her case says she believes Accuser No. 1 was groped by Reinbold.

“Everything she told me made sense,” Assistant District Attorney Tammy Meade said in an interview this month.

Meade has been a prosecutor for a quarter of a century. She thinks this was a case of a male supervisor trying to exert power and control over a female subordinate. That power dynamic, she believes, kept Accuser No. 1 from reporting the incident for years.

“She didn’t sound like an officer. She sounded like a woman who had been victimized. And the reason she didn’t report made sense to me,” Meade said. “Everything she said made sense.”

Accuser No. 1 is the only person who agreed to speak with state agents for a criminal investigation. Meade went through their findings and wanted to charge Reinbold with assault.

But by the time Accuser No. 1 came forward, it was too late. The statute of limitations had expired.

“I hate telling victims that. I hate not being able to help them,” Meade said. “It’s always disappointing to me when I have to tell someone, you know, ‘I believe you. I would love to be able to do this for you. But the statute of limitaitons says I cannot.’ “

Accuser No. 1 is too afraid to have her name published. And she has no physical evidence to prove her case. So, it’s her word against Reinbold’s.

Accusations of intimidation

In October 2020, Reinbold spoke with an investigator from the Office of Professional Accountability. Silent No Longer had released the allegations against him just two months earlier.

Reinbold called the accusations against him “completely untrue.” And he was still hoping to convince the department that his version of the story was the true one.

Reinbold told the department there was “a tremendous amount of slander” being spread by the media. He had started talking to attorneys and was planning to sue those who had spoken out against him.

The captain claimed a group was colluding against him to spread false stories of sexual misconduct. The list of his alleged slanderers included the nanny Erin McDermott and Greta McClain from Silent No Longer. He also named Monica Blake-Beasley, who had voiced her support for sexual assault survivors on Twitter, and Accuser No. 1.

Reinbold requested all the former officers’ personnel files.

That caused the police department to send Blake-Beasley a letter, alerting her that Reinbold had requested her file. Accuser No. 1 got one, too.

“I was immediately, immediately offended,” Blake-Beasley said. “I have a whole file with details of how I was strangled and raped and treated poorly by the police department, on top of my home address, anything in my personnel file. And now he’s got access to it.”

Blake-Beasley filed a complaint with the Office of Professional Accountability. She said she felt intimidated. But even before her complaint came in, internal affairs had opened an inquiry. They wanted to know why Reinbold had requested the files.

“I wanted to show the pattern,” Reinbold told the investigator, “that they got a group of liars together. There’s no other way to put it. And that would be what would be used against them later.”

He said he didn’t realize they’d all be notified. And when the police department confronted him, Reinbold insisted that they were the ones who were lying.

“For them to go to team up in an effort to target or harass me, I wanted that to be a part of the lawsuit as we go forward,” he said.

The department didn’t discipline Reinbold for allegedly intimidating people who had accused him of misconduct. They didn’t discipline him for alleged sexual harassment or assault. But he did get in trouble, for a reason so trivial in the grand scheme of things that it’s almost comical.

A thumb drive.

After Reinbold requested the former officers’ personnel files, the department’s records division told him it would cost about $750 to get copies.

Reinbold was determined to sue his detractors and prove them wrong in court. But he wasn’t ready to shell out hundreds of dollars to do it. So, the department offered to let him look at the documents on a computer and take notes.

When Reinbold first went to view the records, he thought he could take photos with his phone. Then he learned that he was not allowed to use his camera. So, he stopped.

But then Reinbold went back a second time. And, when he thought no one was looking, he transferred the files onto a flashdrive.

Reinbold told an investigator at the Office of Professional Accountability he knew he wasn’t supposed to. But he said “it was just too much information to not acquire.”

The investigator also caught Reinbold in a series of omissions and inconsistencies, including that he had been on duty when he asked for the files despite initially saying otherwise. As the investigator riffled through the evidence, Reinbold asked to stop the interview and speak with Morante, the director of the Office of Professional Accountability.

They conferred away from the investigator. Morante says he asked her if the allegations were “survivable.” She told him she didn’t think they were.

Reinbold never returned to the interview. Instead, the captain accepted a 10-day suspension and requested to resign.

So, Reinbold, despite having been accused sexual assault, intimidation and repeated misstatements to investigators, got to leave on his own terms. He retired with a pension, in good standing.

Meanwhile, Blake-Beasley, accused of policy violations like endorsing a birthday party magician without permission and going back and forth on where she’d placed her utility belt, feels like she got cheated out of her career.

“It leaves officers feeling abandoned. It leaves officers feeling like there is no justice,” Blake-Beasley said. “If you wonder why morale is so low, it’s because officers are going to work not being able to trust the very people who are there to uphold justice. And if you can’t trust the police, who do you go to?”

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.