There’s some truth in a joke circulating among frustrated ICU nurses right now. They ask for their hospitals to appropriately pay them for the hazards they’ve endured through the pandemic. And they’re rewarded with a pizza party.

That’s what happened at Theresa Adams’ hospital in Ohio. The facility across town was offering bonuses. But not hers.

“I heard a lot of noise about, ‘Well, this is what you signed up for.’ No, I did not sign up for this,” she says.

Adams is an ICU nurse who helped build and staff COVID units in one of Ohio’s largest hospitals.

She recently left for a lucrative stint of travel nursing in California. She hopes to return to her home hospital, though she’s a little irritated at management at the moment.

“I did not sign up for the facility taking advantage of the fact that I have a calling,” she says. “There is a difference between knowing my calling and knowing my worth.”

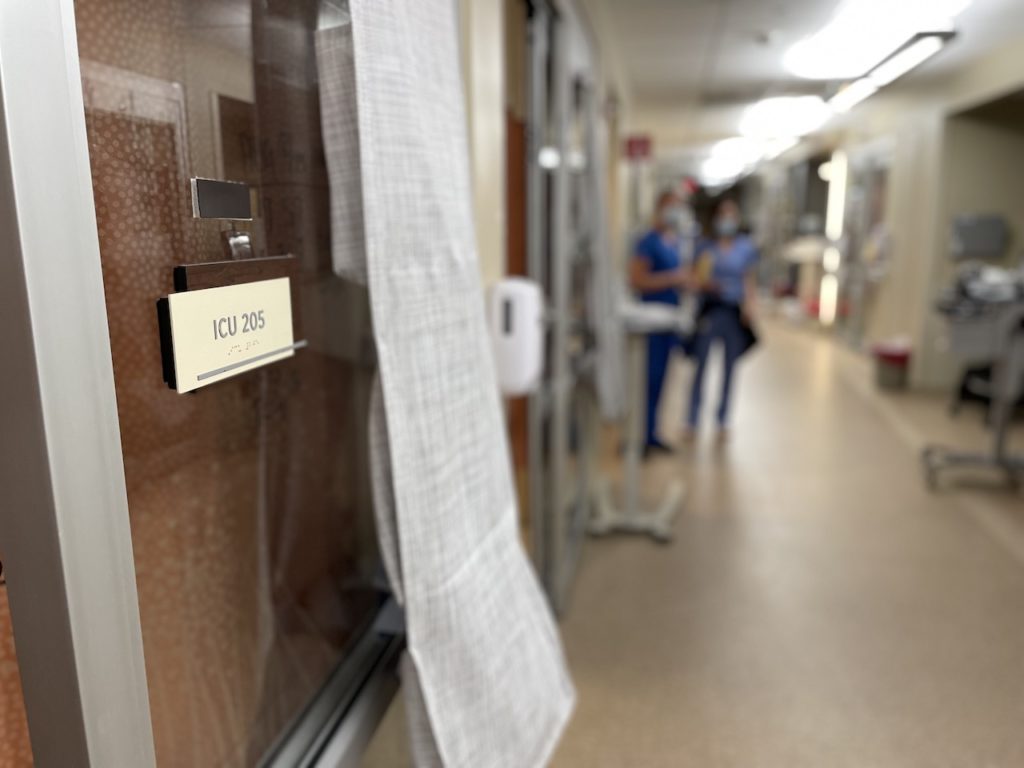

In much of the country, the only thing keeping ICUs fully staffed is a rotating cast of traveling nurses. And hospitals are having to pay them so much that their staff nurses are tempted to hit the road too.

More: Sky-high pay for traveling nurses is both a symptom and cause of the hospital staffing crisis

A reckoning is on its way as hospitals try to stabilize a worn-out workforce.

Traveling nurses have always helped fill in staffing gaps and are paid more for their flexibility. But now some traveling nurses can pull in as much as $10,000 a week, which is several times more than staff nurses earn.

And while some hospitals have been offering retention bonuses and upping pay for staff nurses, the financial perks don’t compare to the traveling bonanza.

It’s become a vicious cycle, though, especially for the most highly trained critical care nurses who can monitor COVID patients on high-level life support machines called ECMO — extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

“Our turnover for ECMO nurses is incredible, because they’re the most seasoned nurses. And this is what all my colleagues are facing too,” says Jonathan Emling, a nurse and the ECMO director at Ascension Saint Thomas in Nashville.

The lack of ECMO nurses has prevented the hospital from taking more COVID patients who need their blood oxygenated outside their body. He says there are no more staff nurses with enough experience to start the training.

“We will train these people, and then six months later, they will be gone and traveling,” he says. “So, it’s hard to invest so much in them training-wise and time-wise to see them leave.”

Cost and quality suffer

And when they leave, hospitals are often forced to fill the spot with a traveler.

“It’s like a bandaid,” says Dr. Iman Abuzeid, founder of a San Francisco-based nurse recruiting company called Incredible Health. “We need it now, but it is temporary.”

Incredible Health helps to quickly place full-time nurses in some of the country’s largest health systems. The number of full-time nurse openings has shot up by 200% in the last year, according to the company.

Some states are subsidizing the expensive travelers to maintain hospital capacity, but for many hospitals, it’s busting their budgets. And that’s especially difficult at a time when they’ve called off elective surgeries where they make most of their money.

“Every executive we interact with is under pressure to reduce the number of traveler nurses on their teams, not just from a cost standpoint but also from a quality of care standpoint as well,” Abuzeid says.

Team camaraderie suffers when the newcomers who need help finding the syringes are also making two or three times more than the nurse showing them the ropes.

Hospitals are going to new lengths to reverse the trend. Some are offering big signing bonuses to permanent nurses, as well as loan forgiveness or tuition assistance for those getting further education. Hospitals have also hiked pay for nurses as they earn new certifications, especially in critical care.

‘Many of us feel like we’re becoming worse at our jobs’

But some are searching even more broadly to fill their nursing needs.

Henry Ford Health System in Michigan has announced plans to bring in hundreds of nurses from the Philippines. Smaller community hospitals are looking internationally too. At Cookeville Regional Medical Center, in a Tennessee town of 33,000, the city-owned hospital is in the process of bringing in its first nurses from overseas.

“The cost for what we pay for a local recruiter to bring us one full-time staff member is more expensive for what we’re going to be spending to bring one foreign nurse,” says Scott Lethi, the chief nursing officer.

And the hope is that the immigrant nurses will stay more than a year or two. Lethi says they’ve hired new graduates who quit after just a few months. A survey published in September by the American Association of Critical Care Nurses finds that two-thirds have considered leaving the profession entirely because of the pandemic.

But the exodus also means the remaining nurses are stretched dangerously thin, caring for more patients at once. And COVID patients are particularly needy, especially those on ventilators or receiving ECMO therapy who may require one-on-one care around the clock.

“My ability to care for people has suffered. I know that I have missed things otherwise I would not have missed had I had the time to spend,” says Kevin Cho Tipton, an advance practice nurse in the South Florida public health system. “Many of us feel like we’re becoming worse at our jobs.”

Providing substandard care weighs heavily on nurses, Tipton says. But in the end, it’s the patients who suffer.