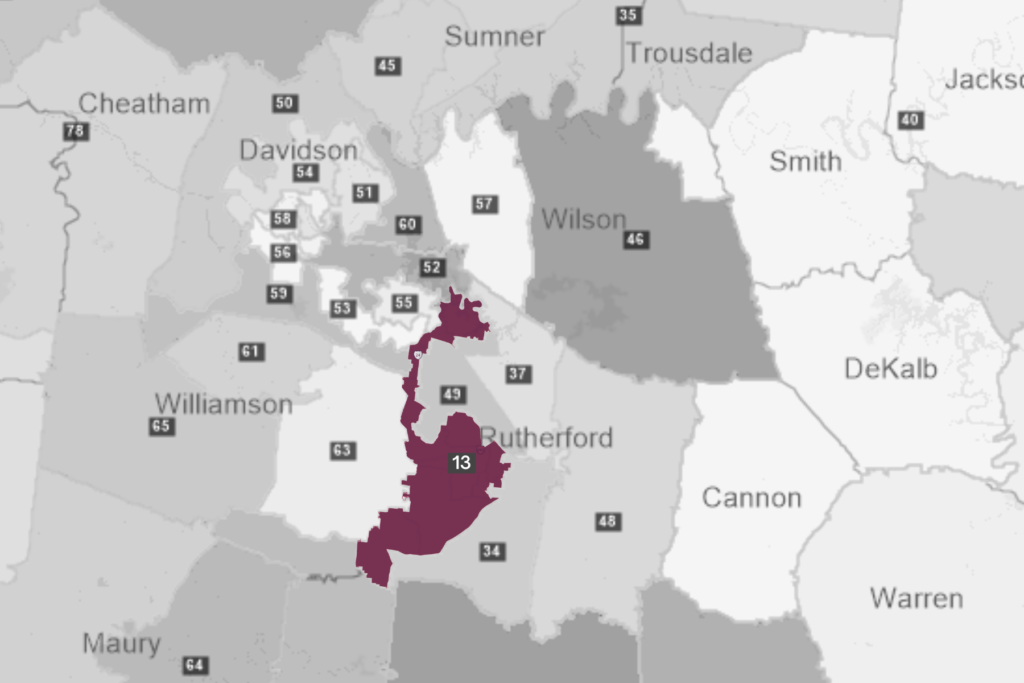

State governments across the U.S. are drawing new congressional and legislative maps based on the latest census, which they are required to do every 10 years. This week, Tennessee Republicans started to discuss their maps in committee, and Democrats are calling them a power grab.

When Rep. Gloria Johnson, D-Knoxville, and political science professor Kent Syler look at the new House districts, they like to play a game you might remember from your childhood.

State of Tennessee TN General Assembly

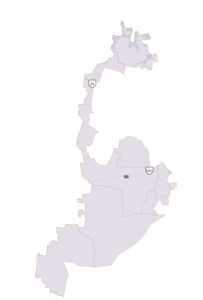

State of Tennessee TN General AssemblyHouse District 13 as proposed by Tennessee Republicans.

“I was playing a game like you do with clouds. Like what is this one?” said Johnson. “Well, this one looks like a dinosaur kicking a rock.”

“It actually looks like an esophagus running down to a stomach,” said Syler.

What they are actually looking at is the proposed House District 13, a seat added in Rutherford County by Tennessee Republicans.

“The way the 13th district has been drawn, it is like the perfect example of gerrymandering,” explains Syler.

Gerrymandering is when districts are drawn to either pack like voters into as few districts as possible or to spread them across multiple districts, diluting their impact.

“If you look at how they basically started in Murfreesboro and western Rutherford County, run a narrow corridor up the interstate and then pulled out a good bit of La Vernge,” said Syler, who teaches at Middle Tennessee State University and is a former chief of staff to Democratic Congressman Bart Gordon. He says Republicans did this, most likely, to weaken the voting power of La Vergne, which leans more progressive.

But even more odd is how the 13th district got placed there. It was previously in Knox County and held by Johnson.

“I don’t really understand why District 13 showed up in Rutherford County and District 90 ended up in Knox County,” Johnson said. “That’s just strange to me. And that’s something you’ll have to ask the Republicans. Maybe they have a logical answer for it. I’m not aware of what that is.”

The chain of events goes back to Shelby County. It lost a seat in redistricting, while fast growing Rutherford County was set to gain one. But rather than move District 90 there, they placed it in Knox County.

Doug Himes advises Republicans that sit on the redistricting committee. He says their reasoning is technical, not political.

“District 89, which left Shelby County a decade ago, is (Knoxville) Rep. (Justin) Lafferty’s number, and 90 made sense a little closer there than Rutherford County’s numbers, which are 30’s and 40’s,” Himes said. “So, it was just a reshuffling of numbering.”

But whatever their reason, the new lines affect Rep. Johnson. She is white, and the new map places her into the neighboring district held by Rep. Sam McKenzie, a Black Democrat.

Now she has to choose whether to run against him, quit altogether or move. And she says she will not challenge him.

“I have longtime said I will not run in House District 15. I won’t run against Sam, and I won’t run in House District 15,” said Johnson. “Since I’ve been in politics that’s been a minority seat, and there’s no way that I would try to change that.”

She says she will likely move to a new address in the next district over.

But she isn’t the only one faced with making a choice. The new maps would pit six Democrats against one another.

“It’s very obvious from the way they drew people into each other’s districts that this was about petty politics and not the voters of Tennessee,” said Johnson.

Relationships disrupted

Sekou Franklin with Tennessee chapter of the NAACP’s says it disenfranchises voters of color in particular.

“What that effectively does is harm the Black vote but you have to go much deeper than just the raw number of Black lawmakers that are there. It disrupts constituency relationships,” said Franklin.

New House Speaker Cameron Sexton says the districts are all fair and constitutional. Credit: Sergio Martínez-Beltrán/WPLN News

While these maps are still under consideration, Republicans hold a supermajority in the Statehouse and could pass the maps without a single Democratic vote. House Speaker Cameron Sexton defends them.

“It’s fair. It’s constitutional, and so we’ve put it forth. The Senate has agreed with it,” he said. “We think it satisfies, and it will prove to be upheld against the Voting Rights Act.”

But Syler, the MTSU professor, says map drawing doesn’t have to be this controversial.

“The only way redistricting is ever going to change is if the politics is taken out of it,” he said. “Which means taking away from the politicians and putting it in the hands of an independent commission.”

Nine states have nonpartisan redistricting commissions. The thought is that not having politicians draw lines would result in fairer maps and less gerrymandering, which Syler believes could lead to less polarized politics.