Delphinium and dianthus. Statice and snapdragons. Purple and pink blooms stripe Charley Jordan’s greenhouse in Woodlawn, Tennessee. The Army Special Forces veteran, with tattooed forearms and a ponytail, calls the flowers his “babies.”

“I have to take care of them,” he says. “It really just focused me back on getting myself well, for one, but also I felt I could share this with others.”

After 28 years in uniform, Jordan is now the guy in faded fatigues selling sweet smelling bouquets at the Clarksville farmer’s market. As much as generating some retirement income, Jordan says it’s an act of healing. Like so many veterans, repeated tours flying Chinook helicopters with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment left him with back problems, traumatic brain injury and diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. He’s recognized as disabled by the VA and relies on a mobility assistance dog.

Flowers have been used for healing throughout human history. But even the act of tending a garden has been found to improve health and lower stress. A small study on veterans with PTSD was less conclusive. But Jordan didn’t know any of that science until recently. He just says putting his hands in the ground is like “plugging in” to Mother Earth for a recharge.

“I get therapy from that. I get a very unbelievable calm feeling once I step foot out here,” he says, surveying his field of zinnias and sunflowers.

Jordan is beefing up on the scientific side of his newfound therapy so he can share the benefits with more veterans. He’s already volunteering at Fort Campbell, leading wounded soldiers as they care for gardens on post. And Jordan is in the inaugural cohort of a horticulture therapy certificate program launched at the University of Tennessee Knoxville this year.

“There are potential therapeutic benefits for anybody that gardens,” says Derrick Stowell, the adjunct professor who started the program in UT’s Department of Plant Sciences.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

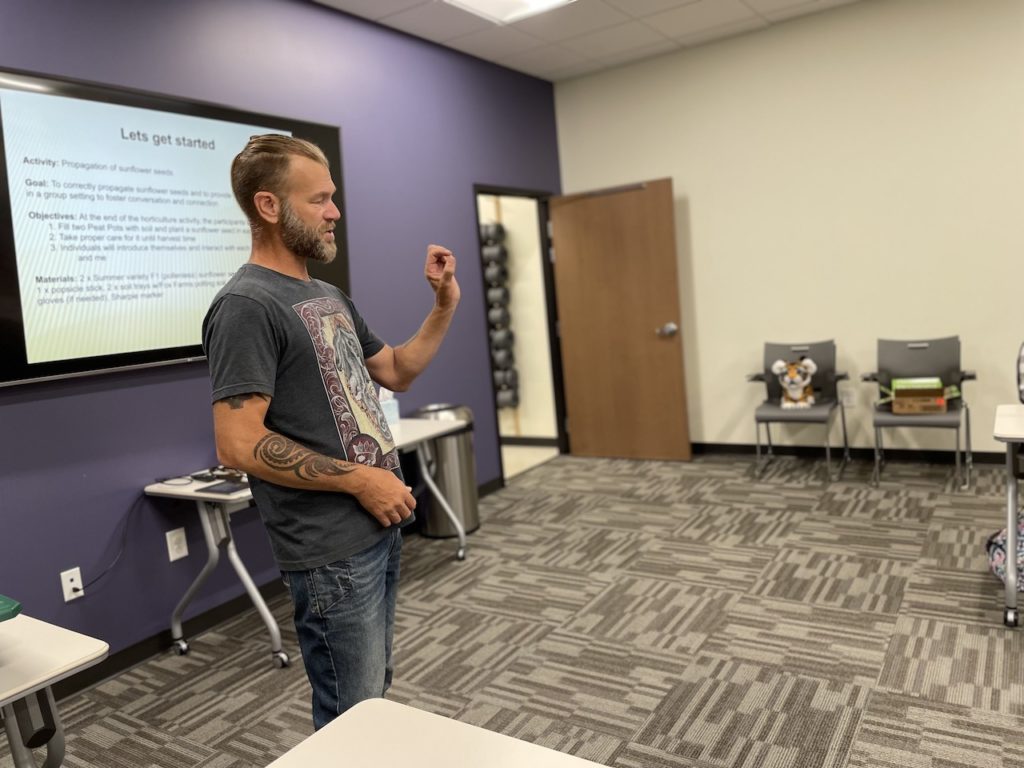

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsArmy veteran Charley Jordan teaches a session on planting and harvesting sunflowers at the Cohen Clinic in Clarksville, where he has been a patient since 2018.

To be considered horticulture therapy, Stowell says someone with the proper training needs to make a treatment plan in which the mental or physical improvement can be measured.

“We’re not just pulling weeds, but we’re improving these outcomes,” Stowell says.

Jordan is already putting into practice some of his coursework. In late May, he led a brief session on sunflowers at the Cohen Clinic in Clarksville, which provides mental healthcare for veterans. Jordan, himself, has been using the clinic since 2018, the year after his Army retirement.

In attendance was Amanda Getto, who served in the early years of the Iraq war and left the military nearly 20 years ago. She says with the help of her daughter she put in a garden for the first time this year, with both vegetables and flowers to attract pollinators like hummingbirds and butterflies.

She was inspired by Jordan, who she also follows on social media.

“I know he still has his bad days like I do,” Getto says. “But watching another veteran succeed and do what they love makes me know that, ok, I can take that step forward and do it myself.”

Charley Jordan submitted

Charley Jordan submittedZinnias are blooming at Jordan Farms in late June.