During Tennessee’s tumult over drag performances — which a new law will restrict starting April 1 — state lawmakers have portrayed their efforts as a triumph of traditional family values over a perceived new threat.

“When we vote here and vote now and we’re voting on this bill,” Knoxville Republican Jason Zachary told his peers on the House floor, “it is about protecting children.”

Yet lost in the fray, opponents say, is how drag itself has been a treasured tradition enjoyed and passed down in Tennessee.

“It’s not like drag just popped up in 2023,” notes historian Philip Staffeli-Suel. “Drag performance or female impersonation has always existed.”

And when he pulls from newspaper accounts of the 1800s, he finds performances tending to happen at “family venues.”

“Where you see these things like circuses and theaters,” says Staffeli-Suel. “It’s going to be the middle-class families — that these representatives today say they represent back then — going to these venues.”

A century later, he points out, the drag queen Bianca Paige the Pantomime Rage frequently took the stage for family-friendly HIV/AIDS benefits, work that the city eventually recognized by naming a street for her.

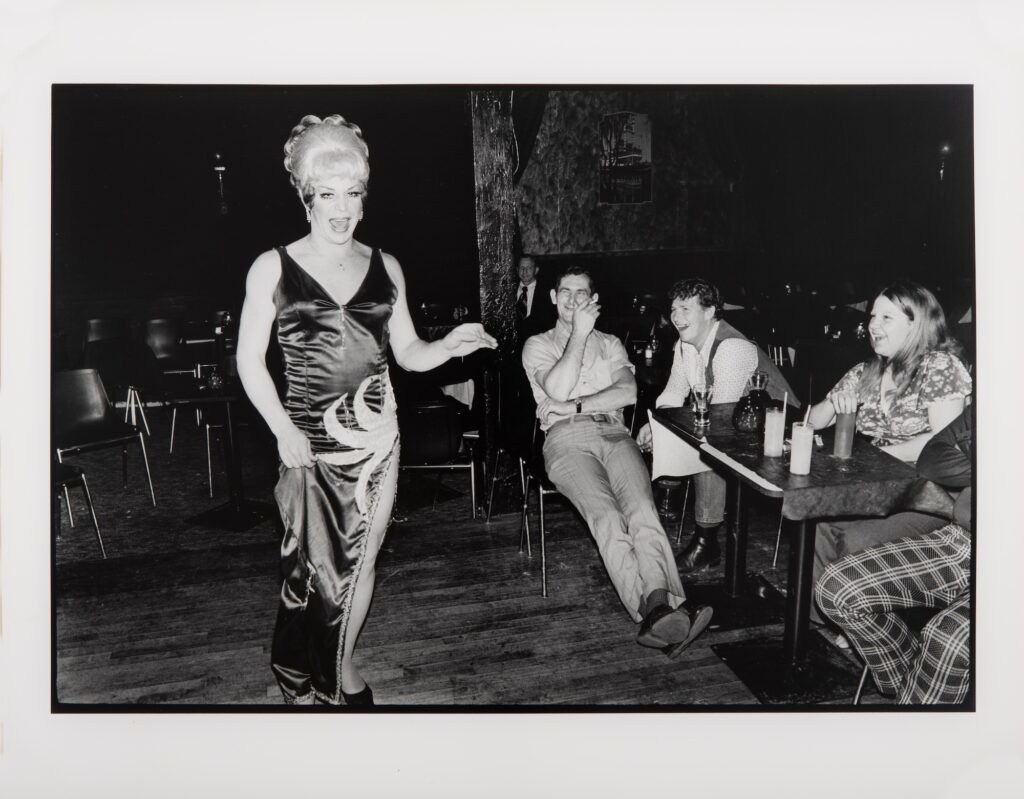

Staffeli-Suel can also reel off the names of numerous clubs that sprang up in downtown Nashville, hosting drag shows alongside the honky-tonks.

In the 1990s, that included The Cowboys LaCage on Lower Broad, where the late performer Coti Collins famously impersonated Reba McEntire — while McEntire herself applauded from the audience.

In the early 90s, I saw Coti Collins / David Lowman impersonating me as part of the Cowboys LaCage show in downtown Nashville. He was incredible. When we were coming up with ideas for our 1996 tour, we decided to take David on the road with us to help with the “Fancy” trick. pic.twitter.com/dcI36GjxFp

— Reba McEntire (@reba) November 15, 2022

Collins was so impressive that she soon landed an on-stage role on McEntire’s tour.

‘We’re just like them.’

In fact, several of country music’s most famous women, Tanya Tucker, Wynonna Judd, Shania Twain, Kacey Musgraves and Maren Morris among them, have since served as judges on “RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

When Twain appeared on season 10 in 2018, viewers also witnessed the rise of the drag queen Eureka O’Hara, who made it to the final three, representing East Tennessee.

O’Hara first put on a wig, and felt seen, in a Johnson City gay bar where an elder performer, Jacqueline St. James, became her drag mother.

After O’Hara’s “Drag Race” success, she was cast on a show called “We’re Here.”

“I wish that some of those people would just watch an episode … watch anything that humanizes queer people,” says O’Hara, “so they can realize that we’re just like them.”

In each episode of “We’re Here,” O’Hara and two other “Drag Race” luminaries, Shangela and Bob the Drag Queen, travel to culturally conservative communities and put on uplifting shows, complete with fabulous costumes and choreography.

“I wanted a job where I could give back to communities like mine,” reflects O’Hara. “These small towns are so stuck in this idea of tradition and family that they forget that we as queer individuals, we as drag queens, we are family too and we love them and take care of them.”

It’s not at all lost on her that this good-hearted mission is the antitheses of how Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers see drag.

Confidence and bravado

Innovative Nashville R&B artist Houston Kendrick connected with a similar lineage after he came to town to make music.

Kendrick, an elastic and expressive vocalist, wasn’t interested in trying to fit any strictly masculine mold in his genre. And he discovered a more freeing path in the landmark documentary about the New York drag ball scene, “Paris Is Burning,” even though it was made before he was born.

“[It] inspired just a sense of liberation for me, to find this one medium where queer people who are marginalized to the nth degree can come and create their own world,” Kendrick explains. “You hear that confidence and that bravado … you’re just like, ‘Damn, you had to dig down there and get that out of yourself!’”

Kendrick infused his richly realized 2021 album, “Small Infinity,” with an imaginative sense of fluidity around gender, persona and mood alike.

And he’ll soon release a music video for his song “Concrete” where he depicts his inner life as a drag ball.

When he previews a clip on his phone, he first appears serving a masc look in overalls, Timberland boots and a gold chain, then a femme one, with a satin caftan and pearls grandly draped around his shoulders. Both receive scores of 10 from the judges, and are joined by a character who represents Kendrick’s “higher self,” as he puts it, “the best of both worlds.”

Courtesy Houston Kendrick

Courtesy Houston Kendrick Houston Kendrick’s forthcoming music video for “Concrete” depicts a drag ballroom scene in which he dons multiple looks.

More than ever, Kendrick believes that leaning on the lessons of his drag forebears and applying them to his own musical world-building is the way to keep moving forward as an artist in Tennessee.

“Is it crazy that I still have this sense of optimism?” he wonders aloud. “I feel like we’re in a renaissance of trans and queer creativity right now.”