I’m not sure where home is for me.

I’m from Nashville but I don’t like the city’s fake niceness. I want us to lean more into our shared humanity and use that to hop into the tough conversations.

When I left for college and job opportunities, I never wanted to come back. But in 2020, I returned to work at WPLN. And in the back of my head, I knew I wanted to work on an oral history of my family.

While reporting on Nashville’s government — and especially housing issues — I wanted to know more about how disruption of community was impacting people. I’d reported on it with a Dickerson Pike mobile home park community, the demolition of the Riverchase Apartments and the wave of evictions. So I picked up “Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America” by Mindy Fullilove, and it challenged me.

“One of the problems with all this displacement is that it breaks people’s willingness to attach to place,” Fullilove says. “And therefore, the willingness to assume responsibility for the health of the earth becomes diminished. Have you ever noticed in very disrupted places, people just throw garbage and they don’t pick it up. Now, wealthy people won’t throw garbage on the street. But they will carelessly throw things out [that] go to a landfill, which is also a burden. So it works at every level of scale that we are, if we are disconnected from love of place. And this interconnection, the interconnected web of all life — if we’re disconnected from that, we’re not going to do what we have to do to save ourselves.”

My idea of an oral history, combined with what I was reporting and reading, started to overlap.

We’re about to dive into why place matters to us as people, how it’s been disrupted and why we should repair or create relationships with people different than us. In my daily reporting these are themes I’ve only scratched the surface of while reporting on how Nashville is evolving.

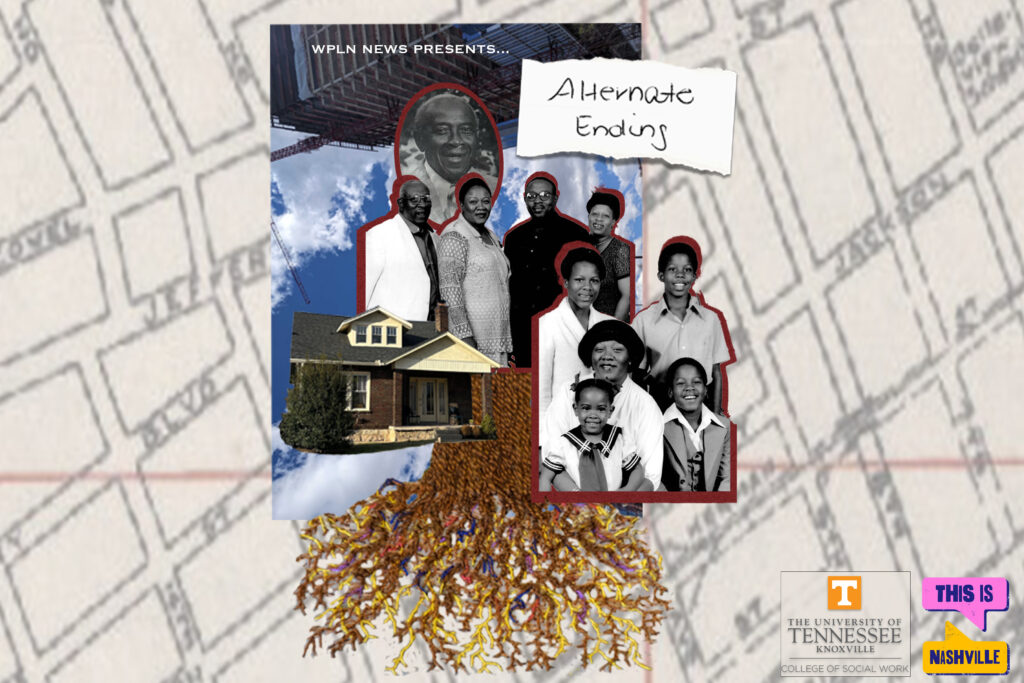

But for me to figure out how to create an “Alternate Ending,” it was essential for me to go to my family to learn. Their life experiences make them experts on the value of interconnectedness.

Listen above for the full documentary experience of Alternate Ending.

Alternate Ending is supported by The University of Tennessee College of Social Work Nashville.

In order for Nashville to grow, displacement has always come first.

We aren’t starting this story at the beginning, when settlers like John Donelson decided they could take the land from Native Americans.

But it’s important to know, Nashville’s land has always been big business. And people of color have always gotten the scraps in order for the city to make some bread.

Black people created their lives around places like Capitol Hill, Edgehill and Jefferson Street. That’s because the government, banks and white residents enforced this as the norm through policies and violence.

But then, throughout the next century, federal, state and local officials forced them out.

I didn’t know this pattern existed until I enrolled in a class at Tennessee State University called “Black Nashville in Public History and Public Memory.” Professor Learotha Williams pushed our class to ask: How can Black people be a part of all the significant locations in Nashville today, yet we hardly see their presence?

“When you don’t know something, somebody can tell you anything because you’re not armed with information. You can’t refute it,” Williams explains. “But once you know the history, you begin to act a little bit differently. In many ways, it’s affirming, it’s inspiring. But also infuriating because nobody has told you that. For most of our experience in this country, what we learned, how we learned it, where we learned it … was under the control of whites.”

While I haven’t personally been displaced, Fullilove did help break down what’s contributed to the lack of connection to place.

- 1930-1960: Strong tight-knit communities. Adults and children looked out and took care of each other. These people know the names of hundreds of people.

- 1960-1980: Communities are starting to fall apart. There’s less of a sense that neighbors can discipline you. So children start creating and getting involved in more chaos.

- 1980-2000: Communities have fallen apart and families are isolated. As a result, families don’t know what to expect when they step out of their house.

So many factors have contributed to this falling apart – first, urban renewal and construction of highways demolished neighborhoods and dispersed people. Later, factories closed because of deindustrialization, some people were unemployed. Then the AIDS, crack and violence epidemics all beat up on social bonds.

Ambriehl Crutchfield

Ambriehl Crutchfield 1730 Knowles Street is a few blocks from Fisk University in North Nashville.

This is the foundation.

1730 Knowles Street. It’s a three-bedroom, one-bathroom bungalow dressed in dark brown brick. The edges of the roof overhang the intimate porch where a wicker bench sits. A yellow-ish cream accents the windows, eaves and door.

“We’re here because it is the foundation of me and my siblings beginning,” my mother Brandi Boyd tells me. “It is the place where we were brought home to. We were taught love. We learned the value of family, friendships, neighbors, neighborhood.”

In 1963, my great grandfather John Cosby moved to the Knowles Street neighborhood, with his three kids, Patricia (my grandmother), John and Anita.

This was a community that was connected through God and His value of generosity. It was something taught in individual homes and that flowed throughout the street.

My great grandfather would come home with a bag of clothes. The three kids would pick two or three objects before sharing with the neighborhood. They were taught never to point out what they did.

“Loving from your heart,” Anita explains. “Give what you want to somebody. And you keep what you think you might not want for yourself. That’s what he taught us. Give what we like for ourself to the next person and keep the other for ourself because it was abundant.”

Government decision wipes out 80% of Black landownership.

Basically since my great aunt Anita was born in 1954, there had been plans underway to construct Tennessee’s interstates. The federal highway administrator didn’t want the highways to impact white businesses or residents.

So, in Tennessee, they routed interstates through predominantly Black neighborhoods like my family’s on Knowles Street. For more than a decade, the community fought against their neighborhoods being ripped apart.

Years later, in 1968, as Anita was preparing to attend Pearl High, a lawsuit against the governor to stop I-40’s path through North Nashville was denied.

It would be built about three blocks from her home, right by Lee Chapel and the service station off 18th and Jefferson. Part of that involved building a bridge over the interstate, which left railing exposed.

“As a matter of fact me and my brother and all of us crawled across it before they put the concrete up there,” she says. “We crawled on the beams to the other side. And when I told Daddy, he got on to us for that because we coulda mighta woulda fell through. You don’t even know.”

The construction of the interstate caused over 100 businesses to be demolished or relocated. This wiped out almost 80% of Black ownership and displaced over a thousand people.

But it would be the next generation figuring out this evolving landscape.

Provided by Brandi Boyd

Provided by Brandi Boyd (top left to bottom right) D’Juana Morris, Jerome Boyd, Brandi Boyd, Patricia Boyd-Olds and Stephen Boyd pose for a family photo.

My Uncle Jerome Boyd and his three siblings grew up in the same brick bungalow. He was born in 1969, right around when the interstate ripped through the heart of North Nashville and the city was stalling to integrate schools.

This was all background noise to Jerome, and my aunt D’Juana Morris. They were just kids exploring their neighborhood just like my great aunt Nita had done just a few years earlier. The mentality is: It takes a village to raise a child. Retired neighbors like Miss Lou Mae are still around, keeping an eye out for the kids.

“What are you doing? Who’s that on y’all’s porch? You know ain’t nobody supposed to be at y’alls house and ain’t nobody, no adults there,” D’Juana remembers hearing from neighbors.

She says when she grew up she appreciated the life lessons and tough talks she had with adults who were trying to protect her. Since neighbors knew more about each other they also knew when somebody wasn’t a member of their community.

Even the kids participated in keeping the adults safe.

“Miss Johnson, three houses up. I’m cutting her grass and taking out her trash, right? So you think I’m going to let anybody throw rocks at her window or drop trash in her yard?” my uncle Jerome asks. “No, you got to respect Miss Johnson, because I’m vested in Miss Johnson. Miss Johnson is vested in me. I’m the young man who helps her. So she’s checking, ‘Are you keeping your grades up? Do you need help with anything?’”

The neighbors would also share their knowledge of fishing and self-defense. They didn’t have to, but they did. The choice to share knowledge and invest time in the next generation left a lifelong impression for my uncle.

Just like the generation before, my family had just about everything they needed on Knowles Street.

But there was a desire for more.

In the early 80s, the “big room” a.k.a. the living room, was a space for an 11-year-old Jerome to daydream. He loved his Encyclopedia Britannica and National Geographics. Both gifts from his granddad, John Cosby.

“I just get tired of seeing the same thing all the time,” he says. “Same people, same thing. It’s like being on a hamster wheel. I don’t know how to say it. I’ve always known there’s more to life. So when I’m reading the books, it takes me there and then I get to see the images. So, that’s what I want to do. I want to see everything. I’m an adventurer.”

The first time Jerome had been around white people was when he was bused to Crieve Hall for elementary school. When he returned to his neighborhood school, Wharton, he met a new friend: Mark Habberly, an 11-year-old white kid from Britain who had recently moved to the states.

“That’s honestly when I learned there’s no such thing as race,” Jerome says. “They looked at it culturally, different cultures. We don’t talk about race, Black, white, you know. We talk about culture.”

Despite Mark being picked on by white kids for hanging out with Black people, they were more focused on finding things they had in common. Over time, Mark and Jerome basically became family. They’d alternate weekends at each other’s houses.

Jerome wanted something new, and he’d gotten a taste of it when he spent the night at Mark’s in Belle Meade.

Even still, Jerome had some perspective on the value of what he already had.

“I always tell him ‘Mark, man — postcard look good,’ ” he says. “That mean the picture on the postcard, if I’m looking at it, it look good. But when I look behind the postcard, ain’t got no substance.

“Well, my postcard is weight. It’s frayed a little bit. But it’s heavy because it’s on the block. I just got to clean up the postcard. That’s it. I got to clean my postcard. You got to rebuild yours.”

‘This place destroyed my family.’

In 1985, my Granny Pat decided to set out to create her own postcard. One of a 36-year-old woman holding down her own home with her children.

So that year they moved out of the house on Knowles Street. First to Cash Street, then to Cheatham Place. This housing project is off Rosa L. Parks Boulevard across from Salemtown. If you cut across the interstate bridge it’s only a six-minute bike ride from Knowles.

But my family’s experience made it feel worlds away.

Cheatham was built in the 1930s for white families using federal funds to create affordable housing. While the Andrew Jackson projects near Fisk were built for Black families. In the Tennessean’s interviews, Cheatham Place families seemed hopeful.

But by 1980, it was declining. Health professionals were sounding the alarm that the economy and environment was causing serious health concerns for residents.

And violence in the projects was a front page story.

The Tennessean went so far as to describe crime as “a way of life.” But what they didn’t say was on the federal level, Section 8 and public housing programs got massive cuts in 1976 and 1982. President Ronald Reagan was reducing the government’s involvement and thought the private market could step in more. The crack and violence epidemics were also making the projects a high-pressure environment.

On an August day back around 1985, Jerome remembers taking a walk with his mom in their new neighborhood. He’s wearing blue jeans and a white t-shirt. Although he was only 16-years-old, he understood playtime was over.

He became the man of the house.

“When you’re young and you’re a boy you can enjoy life, you can choose,” he explains. “You still have options of choosing, of what you want to do and kind of feeling your way through to see. When you’re a man nah, you got to look out for your family. Providing wise.”

The whole looking out for Miss Johnson up Knowles Street mentality is gone. Now it’s about looking out for himself and his family.

On Knowles, there was space to resolve conflict through words. He’d seen his grandfather John Cosby agree to disagree. But in Cheatham, everyone was forced to survive. So that wasn’t how things went down.

Less than two weeks into living there, a fight breaks out where Jerome says he had to show his family wasn’t a joke.

“This right here, it helped me because it made me strong. That’s the 25% of good that it did. The other 75% it was all bad. All bad. This place destroyed my family,” Jerome says. “My trust for people in general, down. Not completely gone, but slim to none. My closeness with my family ain’t the same. It’s cause of this place. The always having to feel on guard 24/7. It was like if I equate it to anything, I have to equate it to prison.”

When I hear my uncle talk about how his experience shaped him, my brain instantly clicks to reading “Root Shock.” In the book, Fullilove explains that disruption to our connection to place “undermines trust, increases anxiety about separating from loved ones and increases the risk for every kind of stress related disease. It leaves people consistently cranky and upset about the world being taken away.”

Julia Ritchey

Julia Ritchey A crane scales a Nashville building that’s being built.

Alternate Ending.

As I’ve covered Nashville, whether it’s wanting a sense of a safe neighborhood, the ability to stay in your home, or more infrastructure to support development, I’ve heard so much frustration and hopelessness from residents in every part of town.

Back in the 1960s, North Nashville didn’t prevail in stopping I-40 from being constructed.

But I do wonder: If it was seen as one of many attacks on community, and a sign of threats that would come to other communities — not just an issue for Black people — would people in other neighborhoods have helped stop the disruption? How could they have expanded their definition of community to include people that look and live differently?

In 2023, we’re still faced with urgent problems. A filling landfill and a housing crisis are just two examples. In Nashville, mayoral candidates are starting to pitch their ideas on how to solve these problems. But arguably our biggest challenge is our lack of trust with one another, which includes people that look and have different values than us. I believe we’ll need to mend these bonds as individuals so that we can get to work.

I can’t say I’ve nailed down where home is for me. But I’m looking for a place that believes an alternate ending is possible — a place where community bonds are lasting, uncomfortable conversations build trust, and where we focus on our similarities and create from there.

“Alternate Ending” is a special documentary project by WPLN’s This Is Nashville.

Ambriehl Crutchfield reported this story. It was produced and edited by This Is Nashville executive producer Andrea Tudhope.

Staff shoutouts to Nina Cardona, Meribah Knight, Steve Haruch, Tony Gonzalez, Michael Robertson, LaTonya Turner, Cynthia Abrams, and Khalil Ekulona.

Special thanks to the community members who participated in our listening session, the folks at Lee Chapel AME, and Rebecca and Trey Hamilton.