Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2012 for the 150th anniversary of Fort Negley’s origin.

Nashville’s Fort Negley was built for war, and construction began in 1862. Union officers considered the stone fortress a show of strength and military might. Instead, the fort’s enduring story belongs to the black laborers, both slave and free, who were forced to build it.

Looking North from Fort Negley, you don’t just see downtown Nashville, you stand higher than the tops of its tallest buildings. From their perch on what was then known as St. Cloud Hill, soldiers could look in any direction, protected by walls made of large stones quarried from the hill itself.

Standing behind a parapet, Bobby Lovett considers just what kind of effort the building took. He estimates it would take at least two people to move one of the limestone boulders. After all, each is too big for a grown man to put his arms around. “I know I couldn’t lift it without breaking my back,” Lovett says.

The historian has spent years studying the people who hoisted and stacked those rocks. He says many were better educated than you’d think, thanks to clandestine schools. Some had been born free, but most had been slaves, and all of them were black.

With the ‘Blue Men’ Comes Hope

Nashville fell under Union control early in 1862. As Yankee troops in navy blue marched into town to the sound of their regimental band, little boys with dark skin and bright smiles ran through the streets ahead of them, crying out the good news. Lovett says the news that had trickled into the city made it clear that with the Union Army comes freedom.

“Everywhere they had gone so far,” he says, “fugitive slaves were essentially free.”

While the Army didn’t set out to free anyone, General Ulysses S. Grant had been forced to craft policies for dealing with slaves who were captured along with Confederate troops and those who sought refuge near Union encampments. He essentially barred troops from returning escaped slaves to their masters and sometimes offered them work for pay.

Once the army settled into Nashville more blacks came, leaving behind slavery on farms and plantations across Tennessee and from neighboring states to take advantage of the Union policy. They were called “contrabands,” and state historian Walter Durham says the Northern soldiers didn’t know what to make of them at first. “They were fighting a war they didn’t know they were dealing with this serious social problem.”

Another Kind of Slavery

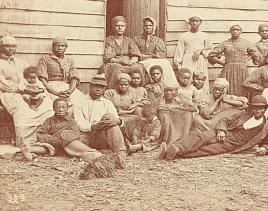

Whether they were technically slaves or freedmen, the Army treated contrabands much the way the slave owners had: a source for heavy manual labor that could be worked very, very hard. By August of 1862, when it was time to start building defenses around Nashville, so many contrabands were already building and repairing railroads and bridges that Lovett says the Union was desperate for more black laborers.

Their solution, Lovett says, was to, “just sort of ignore part of the Constitution, to tell you the truth,” and start impressing workers against their will. Anyone who looked black and strong enough was forced into service. They could pick people up off the street, and did, but Lovett says the officers quickly decided one of their best bets was to raid black worship services. He describes the scene at his own church, First Baptist Capitol Hill. “They just simply wait until the church services are good and loud and the cavalry surrounds the little building and they march every able-bodied person out.”

It’s easy to think “able-bodied” means young adult men, but the Union impressed black women, too. Children as young as 13 were put to work, along with adults as old as 55. They were forced to march to the top of St. Cloud Hill and put to work for the Union Army in conditions that were miserable.

The workers slept on the ground with no tents and little provisions. There were no outhouses, so the site was contaminated with human waste. Their drinking water likely wouldn’t be considered potable today, since it came from a creek that ran next to the city cemetery.

From mid-August through early December, the laborers were worked from sunup to sundown, or as an old phrase would put it, “can see to can’t see.” The work itself was strenuous, possibly even harder than what they’d previously done as slaves: digging, dragging, lifting, moving, blasting and cutting with armed Northern soldiers as overseers.

Roughly three thousand were pressed into service. About a quarter of that number died from disease, injury, or exposure. Lovett says building the fort was as deadly as going into battle would later be for black soldiers.

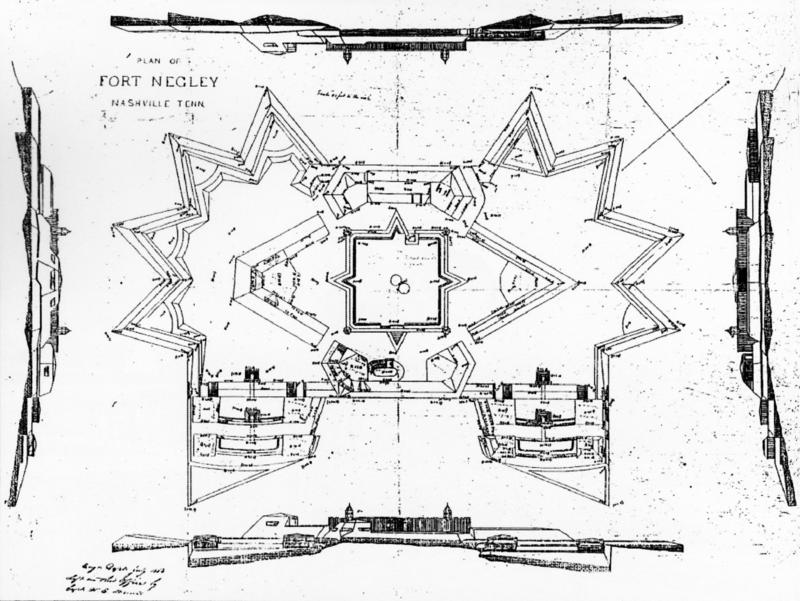

Blueprints show the fort was built in a Spanish-style star configuration.

Better Than The Alternative

About a month before their work was complete, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked supply lines near the city. Union officers fired a cannon already in place at Fort Negley to scare Forrest’s horses. When the workers heard that artillery, Lovett says they asked the officer in charge if they could help defend the fort, but policy didn’t allow black men to carry weapons.

That didn’t stop the workers. They formed lines of defense holding only their tools; they bravely stood with picks and shovels to potentially face rifles and sabres. As bad as life was on the work site, Lovett says they knew the Confederate policies for dealing with captured blacks were worse.

“They are to be returned to slavery and these people working on this fort are not about to be returned. They know they’d better die or they’d better die fighting.”

Thankfully, it never came to that. That day’s skirmish didn’t reached Fort Negley’s walls. In fact, the fort was never the site of any real fighting, not even two years later during the Battle of Nashville.

Free At Last

When construction ended in December of 1862, the workers were allowed to go. Compensation for their work was slow in coming, and many never got any pay. Some fought for the Union Army once it started accepting black troops, others seem to have moved on, likely looking for a better fortune somewhere else. Still, quite a few stayed in Nashville, living in squalid, under-supplied contraband camps that they eventually transformed into thriving neighborhoods like Edgehill, Edgefield, and Jefferson Street.