In the Nashville mayor’s race, multiple claims made by candidates on their campaign websites rely on inaccurate statistics or arrive at simplistic conclusions.

WPLN reporters recently reviewed the leading candidates’ websites, finding varying degrees of problematic information from Mayor David Briley, state Rep. John Ray Clemmons, Councilman John Cooper and retired professor Carol Swain.

In all, the websites offer a glimpse into what the candidates believe are the most pressing concerns facing Nashville. And by understanding where their claims go awry, voters can better understand how important data points about the city are tracked and — at times — shaded to support a perspective about the city.

Contrasting Campaign Approaches

The candidates’ websites vary widely in approach and tone, and rarely link to direct source material. They also tell different stories about life in Nashville.

One candidate, Cooper, chose to be hyper-detailed. He’s a self-styled “numbers guy,” and his site features statistic-heavy paragraphs about demographics, teacher pay, transportation, Metro finances and the councilman’s own voting record. His campaign even turned the material into a 47-page policy booklet.

That approach also opens Cooper to more scrutiny, as reflected in the findings below. In some instances, his campaign has updated assertions after WPLN questions.

Swain, meanwhile, rebutted most of WPLN’s findings.

Clemmons initially published a website with few verifiable facts or claims, then rolled out a much-expanded version just before early voting began. His campaign updated two items after questioning.

And Briley largely avoids statistics or forward-looking promises — ultimately providing relatively few facts to be checked. His site focuses on listing the programs launched during his administration.

Here’s what the fact check found on more than two dozen claims on candidate websites.

DAVID BRILEY

The current mayor includes six issues on his site. For the most part, Briley lists specific actions he has taken in office thus far and makes fewer promises about what would come next. That approach differs from the others.

Claim 1: “The Mayor’s administration has developed a new online portal, hub.nashville.gov, to help citizens report problems and code violations.”

Check: Somewhat true. The hubNashville system was actually created during Megan Barry’s administration, launching in October 2017. But Briley’s team defends the use of “developed” because his administration launched an app version, added two staff members and put $300,000 toward the city’s information technology department for hubNashville activities. The campaign added mention of the app after WPLN questioning.

Claim 2: “Mayor Briley signed an executive order making Nashville the first city in the South to recognize LGBT-owned businesses as a procurement category.”

Check: True, says a national LGBT advocacy group that also hoped the executive order would “encourage more mayors to proactively include the LGBT community for the optimum social and economic health of their cities.”

Claim 3: “The [Under One Roof housing] plan includes a $500 million public investment in affordable housing over the next 10 years, with a challenge to the private sector to put in another $250 million.”

Check: This is the plan, but making it a reality is less certain. Specifically, the $250 million from the private sector isn’t guaranteed. Briley is asking for that buy-in. But in what form (money, housing) is less clear. A spokesman says the administration is “in conversations with multiple parties — companies, developers, investors and individuals — to build more affordable housing.”

More: Nashville Pledges $500 Million To Build Mixed-Income Housing

JOHN RAY CLEMMONS

The Democratic state lawmaker shares an eight-point vision that promises leadership and policies that aren’t the “status quo.” Initially, the Clemmons site included few specific or verifiable claims. But it was overhauled and expanded the week that early voting began. A campaign spokesman says the timing allowed for ideas from community listening sessions, and so that assertions would be “right.”

Claim 4: “In six years, our city is estimated to have a shortage of 31,000 units for middle and low-income families.”

Check: True, according to The Housing Nashville Report. However, the methodology behind it is not clear. It does not factor in any additional affordable units that could become available, for example. On the other hand, some affordable housing advocates think it’s vastly

under-counting the number. This figure is often cited by both Clemmons and Cooper.

Claim 5: “Every week our city gains hundreds of new residents as our rapid growth continues.”

Check: False, but the misperception is widely held. It’s actually the entire region, including cities like Franklin and Murfreesboro, that’s gaining population at this rate. The city of Nashville alone is seeing moderate growth. The city grew by 69 people per week from 2017 into 2018; it grew by 30 people per week the year before. (Those numbers include births, as well as people moving here.) The campaign has updated its site to refer to the region, emphasizing the multi-county strain on traffic and affordability.

More: Transit Ad Inflates Number Of People Moving To Nashville

Claim 6: “My administration would develop a Community Land Trust to oversee development projects.”

Check: Nashville already created a community land trust in 2017 to foster affordable housing. The campaign says it meant to say that Clemmons would further develop it with more funding. Clemmons also wants to establish a land bank that would identify Metro properties that can be provided to affordable housing developers. That would be new.

Claim 7: “It is also essential the Metro government finally invests in body cameras for every officer and dash cameras for every vehicle … yet budget after budget has failed to fund this need.”

Check: Yes and no. Supporters of policing cameras, and Clemmons, are certainly frustrated by the pace of their rollout. But Metro has allotted at least $23 million to the camera program in two recent years as camera testing and the procurement process plods along.

Claim 8: “While [short-term rental properties] provide residents with supplemental income, we’ve seen little to no enforcement of the current regulations.”

Check: No enforcement? No. Enforcement has been a challenge, and Metro Codes says it is has a backlog because of understaffing. But since 2015, the department has brought more than 2,000 STRP operators into compliance after issuing warnings. Nearly 300 cases led to court injunctions. The Clemmons campaign defends its premise that enforcement has been too light and too late.

Claim 9: “MNPS currently spends roughly $10,000 per-pupil annually, which is far … below many of our peer cities.”

Check: True. According to Metro Schools, the per pupil dollar amount for the 2020 fiscal year is $10,400.

Claim 10: “The starting pay for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree is $43,000 a year.”

Check: This figure comes from this Metro Schools pay scale, although the district told WPLN that a new teacher with a bachelor’s degree and no teaching experience has a starting salary of $44,663.89.

Claim 11: “The annual [teacher] supply stipend [is] $200.”

Check: True. The district says individual schools also have additional funds for supplies.

Claim 12: “Firehouses are falling into disrepair, with only one additional station added since 2001.”

Check: True — Station 35 on Hobson Pike opened in 2011. An additional three stations have been renovated and eight reconstructed.

Claim 13: “In the 1990s, Nashville had 14 ladder trucks designed to handle tall buildings. Now, with more skyscrapers than ever before and 30 years later, we only have 12 trucks available.”

Check: Yes, in 1991, Nashville reduced its ladder trucks “to implement heavy rescue companies,” according to the fire department.

JOHN COOPER

The councilman paints Nashville as a struggling city that he would work to improve. His campaign said he chose to roll out lengthy policy pages “out of respect for the voters,” saying he is responding to the public’s desire to see details about Metro policy.

Claim 14: “[Briley’s affordable housing] plan envisions increasing the city’s contribution by $5 million a year. Mayor Briley’s current budget proposal amazingly does not include any new funds.”

Check: Correct. In Briley’s big announcement for his Under One Roof proposal, he said he will give the Barnes fund $150 million over the next 10 years — which averages out to $15 million per year — yet the mayor’s current budget still allots the same $10 million for the Barnes Housing Trust Fund. A Briley spokesman, however, says this number is fluid year-to-year. In other words, don’t simply divide the total goal by 10.

Claim 15: “Approximately 18% of MNPS students missed at least 10% of school days last year.”

Check: True. During the 2017-2018 school year, the chronic absence rate was 18%.

But the district is expecting a lower rate for the latest school year: 15.8%. (Official numbers from the state Department of Education have yet to be released.)

Claim 16: “Over half of teachers are leaving the district within their first three years of teaching.”

Check: False, and Cooper’s campaign updated this in response to WPLN. Metro Schools reports the district retains 62% of the teachers at the third year. The campaign said it mistakenly characterized this Tennessean article.

Claim 17: “Spending on schools makes up about 45% of the budget of most large cities; Nashville has devoted just under 40% of our budget to schools in the last two years.”

Check: This is complicated, and the fact check led to substantial changes to the Cooper campaign site. In large cities, roughly 40% to 45% of the budget goes toward funding public schools, says Sean Corcoran, a Vanderbilt University adjunct professor who studies local public education finance. A WPLN review found a range of spending in cities of similar size to Nashville. The Cooper campaign couldn’t cite a source, so it has since adjusted its website.

Now, for the second half: According to Metro’s budget for this year, about 39% goes toward schools. Increasing the share of the budget going to the school system would be a giant task. To increase schools funding to 45% of Metro’s budget would require shifting approximately $135 million — meaning either cuts elsewhere in Metro, or finding more revenues.

City leaders have had fierce debates over much smaller sums. The Cooper campaign backed off from this goal, now hedging to a more simple promise of increasing schools funding.

Claim 18: “Between 2011 and 2017, rents in Nashville rose by 64 percent.”

Check: The premise — that rents are skyrocketing — is solid. The data is from a Metro Human Relations study, and that study took it from a website called Rent Jungle. While this name doesn’t evoke a strong reputation, rent trends are often pulled from internet broker sites, including Zillow. To keep it clean, WPLN redid the math on the average and median rent for 2-bedroom apartments from 2011 to 2017. According to Rent Jungle, the average price rose 67%. According to Zillow, the median price rose 71%.

Claim 19: “Between 2014 and 2018, auto thefts increased 280 percent.”

Check: No, but the campaign says this was a typo and has since updated its site. According to Metro police, car thefts increased 183.35% in that time, from 1,099 in 2014 to 3,114 in 2018.

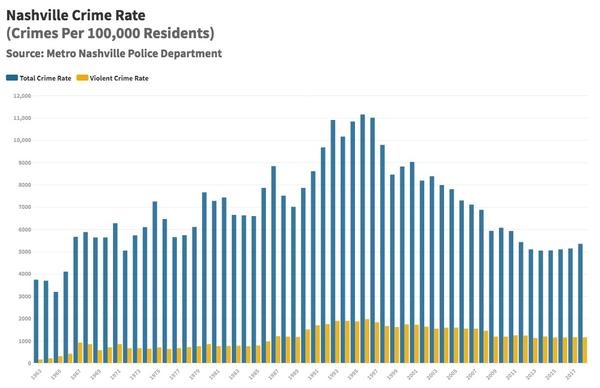

Claim 20: “Violent crime last year was at a level not seen in a decade. Yet our police department is understaffed by more than 130 positions.”

Check: Both parts of this are questionable. The count of violent crimes was higher in 2018, but MNPD data show the violent crime rate — which accounts for population growth — was lower. In fact, compared to 2018, the violent crime rate was higher in all of the years from 1987 through 2012.

Meanwhile, the police department does have vacancies, but the number has come down. As of July 3, there were 99 positions unfilled.

Claim 21: “Of the 1,435 MNPD sworn officers, only 157 are black and 137 are women.”

Check: This basically checks out. As of July 3, MNPD has 1,412 sworn officers, with 154 black officers and 131 female officers.

Claim 22: “As of April 24, 2019, 31 sworn officers have resigned from the force this year. This represents a 93% increase in resignations compared to the same period in 2018. It costs the city approximately $75,000 to recruit and train each new officer.”

Check: While some of the exact numbers differ, the premise is true. The police department says 27 sworn officers — not 31 — had resigned as of April 24. Cooper is right about the percent increase. Regarding the cost to recruit and train officers, MNPD says it costs $70,910.89 per officer. The campaign says its $75,000 figure is one used by police leaders.

Claim 23: “Metro has built only 6.2 miles of new sidewalks since 2016.”

Check: This was true as of May 2019, documented in this Metro Public Works report.

Claim 24: “Only 12.9% of Davidson County households live within a half-mile of high-frequency bus service at rush hour.”

Check: This is true — although it is slightly different than what WeGo estimates. WeGo counts at least one additional bus route as “high-frequency,” but the agency generally accepts the methodology from website alltransit.cnt.org.

Claim 25: “It is clear that Nashville would benefit from a move to more of a grid model as well, with more cross-town and connector routes.”

Check: This is a complicated. At core is a question of how, or whether, Nashville should alter what has long been a hub-and-spoke bus system, which sends almost all bus trips through the downtown station.

“Shifting to more of a grid model is not without trade-offs — fewer routes going downtown means more people will probably have to transfer to get to downtown,” WeGo tells WPLN.

Agency leaders do want to add more cross-town bus routes, which avoid downtown. But WeGo is quick to note that local geography, the design of the interstates, and the amount of activity downtown — including more than 60,000 jobs — have all contributed to the current design.

Cooper and Clemmons both encourage a grid.

Claim 26: “Metro’s revenue grew by over 19% between 2013 and 2018.”

Check: True. This is pulled from comprehensive annual financial reports from 2013 (Page A-5) and 2018.

Claim 27: “One in four urban residents does not have access to a vehicle.”

Check: False. This simplifies a finding from a local think tank and inflates the number of residents without vehicles. Census numbers show that across all of Davidson County, about 7% of households are without a vehicle.

Looking at just the urban areas is more difficult, but ThinkTennessee found that in some council districts, a range of 16% to 26% of residents lacked regular vehicle access. That finding — which is really about smaller pockets of need, not the entire urban area — was simplified when it was referenced by Walk Bike Nashville, which the Cooper campaign cited as its source. Only in Council District 17 are one in four lacking vehicle access.

CAROL SWAIN

The former Vanderbilt professor identifies three priorities: crime reduction, transportation and housing, along with six additional long-term priorities. In a written response, Swain roundly rejected WPLN’s fact checks, either standing by her figures or offering critiques of various Metro agencies.

Claim 28: “I will start by IMMEDIATELY addressing the 50 already identified intersections where turning lanes and better-synchronized traffic lights can relieve congestion.”

Check: This is at best confusing. For starters, no transportation agency has been able to locate any such list of “50 already identified intersections” in need of turn lanes. WPLN asked Metro Public Works, TDOT, the mayor’s transportation advisor and the Greater Nashville Regional Council (which disburses federal transportation funds). Officials note that traffic lights were re-timed in 2017, and that merely adding turn lanes is an overly simplistic approach to traffic management.

There are other noteworthy lists available. In 2012, 28 intersections were identified for various improvements. In 2016, former Mayor Megan Barry directed improvement work to begin at 17 intersections. And Metro once studied the 50 most dangerous intersections for pedestrians.

Swain did not provide a list of identified intersections but stands by her plan. She suggests Metro can still improve its traffic signals by converting to adaptive, sensor-based technology that allow for more rapid responses to conditions.

Claim 29: “In 2018, the city had 9,179 reported potholes and 18 employees working to prioritize and patch them.”

Check: This is false: The claim is a dramatic undercount of the number of potholes in Nashville last year. Metro Public Works keeps close track and says there were almost 43,000 potholes that the department filled. Typically, 15 employees work on potholes, with additional crews available during high-volume times.

Swain says her number came from a newspaper story about potholes reported to hubNashville in the first three months of 2018. “Regardless, my point is either true or extremely true, that the city has a huge number of potholes in need of fixing,” Swain said.

Claim 30: “Our crime rate is on the rise and out of control.”

Check: It’s hard to quantify “out of control.” Swain is right that Nashville’s overall crime rate has risen each year since 2014. MNPD records show the total crime rate per 100,000 residents increased from 5,041 in 2014 to 5,347 in 2018.

But even with that uptick, the crime rate since 2013 has been lower than the entire span from 1973 through 2012. In some years in the 1990s, the crime rate was double what it is now.

In a written response, Swain defends her stated trend by insisting on looking only at the recent years, as well as cautioning that crime reporting has changed over time. She says solutions to current crime problems should not be based “on the nature and number of crimes long, long ago.”

Claim 31: “Nashville now has the highest debt per citizen of any city in the nation.”

Check: Shaky claim. There is a WalletHub survey that puts Nashville up with Washington, D.C., and San Francisco as having the highest long-term debt per capita, as in government-backed debt per resident. But Nashville’s finance department questions WalletHub’s methodology and the sources of data.

However, the city’s bond rating, which is currently at AA, could be better. Comparable cities with higher ratings include Austin and Charlotte, which means they can borrow money with lower costs.

Swain defends the study in her response and doubled down, saying that Metro Finance has “been complicit in wasting millions of our taxpayer dollars every year and encumbering future generations of Nashvillians with long-term debt they will be hard-pressed to pay off.”

WPLN reporters Tony Gonzalez, Samantha Max, Blake Farmer, Meribah Knight and Sergio Martínez-Beltrán contributed to this report.