Many of Nashville’s tunnel rumors were tough to confirm as anything more than legend. But there are a few things underground that probably should inspire more awe: the city sewers.

Easily underestimated, and common to every major city, it turns out that Nashville’s sewer and stormwater tunnel systems rank as significant engineering triumphs (view map).

They run for miles below ground. And at least one brick sewer – built by hand – has been in operation for nearly 130 years.

“When you go digging in downtown, you can find some structures that you would not have guessed would be there,” said Ron Taylor, clean water program director with Metro Water Services. “You might even call it a maze of pipes through downtown Nashville.”

As part of the Curious Nashville series, WPLN combined the expertise of Taylor with other engineers and builders, plus historical accounts and maps, for this guide to Nashville’s three largest sewer tunnels.

Metro Water Services and the Tennessee State Library and Archives

Metro Water Services and the Tennessee State Library and Archives Known in 1892 as the Lick Branch Sewer, the city’s largest sewage and stormwater tunnel flows eastward just a few blocks north of the state capitol.

The Biggest Of Them All

Nashville’s oldest and longest sewer, constructed in the 1890s, was long known as the Lick Branch Sewer – now referred to as the Kerrigan Regulator.

Like the other tunnels in the city, this one follows the route of a creek. Roughly, it flows from the Vanderbilt University football field, through Centennial Park, near the Sounds baseball stadium and into the Cumberland River in Germantown (near the former Kerrigan manufacturing plant).

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNBecause sewage and stormwater flow together, warning signs are common near outflows.

At its largest, this tunnel is 16 feet across and the thickness of seven layers of bricks, Taylor said.

Of note, it is one of several “combined” tunnels for sewage and stormwater. That’s actually an infrastructure problem that Metro spent more than a billion dollars to correct by creating separate systems for sewage and rainwater.

Until 1958, all of it flowed together directly into the river without treatment. Each year, about a dozen large rain storms still force the release of sewage into the river – down from about 60 such “overflows” per year. Between 1990 and 2007, the city reduced sewage discharges by 99 percent (learn more).

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNThe Central Treatment Plant pumps sewage through massive pipes – the final step before discharge.

Most of the sewage flows to the Central Treatment Plant on 2nd Avenue North, not far from where the Kerrigan dumps into the river.

On a tour of the plant, Taylor showed off a pumping room that features a series of towering, 80-foot-tall sewage pipes.

“People are just so surprised at the magnitude, the size, the complexity … things that they think just disappear,” Taylor said.

One of the plant’s challenges is managing large debris that funnels into the system.

“We have found ladders, about 6 to 8 feet in length, a car tire with the wheel still in it, sections of railroad cross ties, bowling balls,” said supervisor Michael Binkley. “Almost anything you can imagine.”

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNThis creek in East Nashville becomes a manmade sewer tunnel along Apex Street.

East Nashville’s Behemoth

Not far across the Cumberland River, another large tunnel appears as a concrete culvert. This is the Washington combined sewer outfall (CSO), which originates about two miles northeast alongside Ellington Parkway.

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNThe Washington CSO can be seen on the east bank.

At its largest, this tunnel is 11 feet across.

What separates it from the others is a facility built at its mouth, along Apex Street.

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNThe Apex Street facility guards against large debris entering the tunnel system.

This is where a creek becomes a manmade, concrete tunnel. But before anything flows in, it first passes through a metal screen designed to filter out the damaging debris that’s feared by Metro Water.

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNThe mouth of the Wilson Spring Storm Tunnel is visible just below the Ascend Amphitheater.

The Mother Of All Tunnels

Nashville’s earliest large tunnel dates to the 1880s and flows just below Demonbreun Street in downtown before emptying into the Cumberland.

At its largest, it spans 12 feet across. A massive 1967 expansion was well-documented (read a full account from Building Magazine).

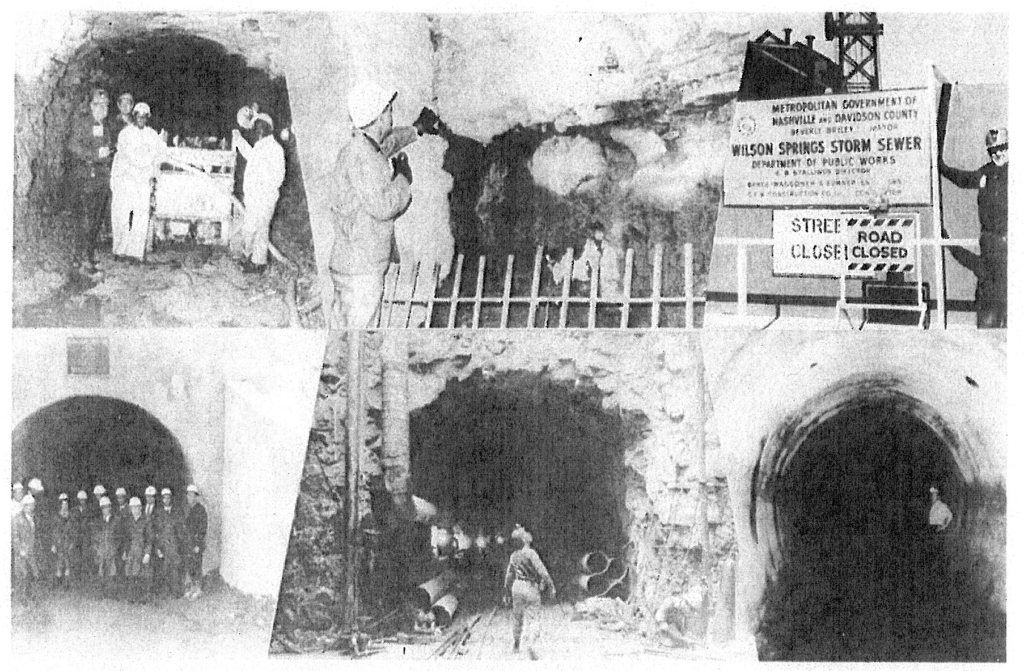

Metro Water Services

Metro Water Services Photos from the late 1960s show crews carving the Wilson Spring Storm Tunnel

And in the late 1990s, the sewage and stormwater roles were separated, making it the most hospitable of the city tunnels. Adventurers have, in fact, entered this tunnel by canoe.

Taylor cautions against such exploration, as intense rain can create a flow of 10 feet per second, or about 1 billion gallons in a day (comparable to the low flow of the Cumberland).

The tunnel is also home to bats, according to one urban spelunker.

As it stands now, this tunnel is gaining a lot of attention because of its location beneath a high-growth area, particularly for large skyscrapers.

Construction crews need to know exactly where this tunnel is, but that’s not simple.

“A lot of the roadway layouts have changed since this work was done,” said civil engineer Don Williams, with Gresham, Smith and Partners. “The biggest change is the construction of Korean Veterans Boulevard. And so it’s a little bit difficult to tell exactly where this tunnel is, even looking at these plans.”

Crews are locating this tunnel. And in the process, there’s a chance that they’ll encounter other interesting things.

In the past year, the tower project at 222 2nd Ave. S. turned up a glimpse of a small tunnel – perhaps 3 feet across – said Michael Hayes with C.B. Ragland Company.

“When we dug our hole, we found another … 6 or 7 feet down, under a parking lot,” he said. “We don’t know where it went.”

A similar account circulated in that area in the late 1990s.

“We managed to find several connections, some of which were to basements in buildings along Second Avenue … maybe 10 feet below street level,” said Taylor, with Metro Water. “They ran into some of these cavern-like structures, that appeared to extend into the basements.”

So far, firsthand accounts and photos of those encounters have not been forthcoming.

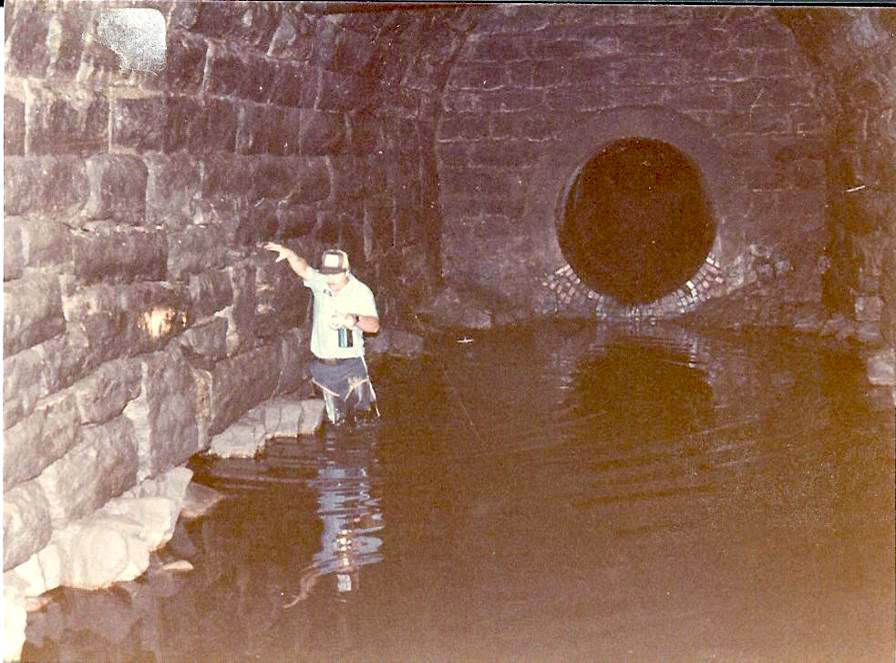

Metro Water Services

Metro Water Services A Metro Water Services employee travels underground where the Wilson Spring Storm Tunnel passed beneath a stone bridge.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))