Feb. 27. That was the day Dr. Emma Rich first realized COVID-19 might become a problem at the Bledsoe County Correctional Complex.

Rich, a physician at the prison, says the issue came up during a medical staff meeting. Someone said female inmates had started hearing about the new virus making its way around the globe. And they were anxious.

“What was asked at that meeting was: ‘What is our plan?’ And the plan is, there isn’t one,” Rich told WPLN News.

The Bledsoe County Correctional Complex soon became the first Tennessee prison to have a major outbreak of the coronavirus. About 600 inmates and staff have since tested positive for the virus, making Bledsoe one of the largest hotspots in the country.

WPLN News interviewed more than a dozen prison employees and inmates’ loved ones, and reviewed internal documents and letters from prisoners. They reveal multiple missed opportunities to prevent the spread of the outbreak.

Staff, inmates and their relatives say officials were unprepared when the virus first hit and have scrambled to keep up since.

They describe nurses who were told not to wear face masks. Sick and healthy prisoners locked together in a cell. Days without showers or calls home.

“This was 100% preventable,” Rich says. “What they’ve done is unforgivable, as far as I’m concerned.”

Rich took a leave of absence on March 31, after her supervisors told her she couldn’t wear a mask to work. They said the prison had to preserve personal protective equipment for patients who had already tested positive for COVID-19, or who her supervisors considered “COVID-19 suspect.”

Rich’s supervisors told her they were following guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Tennessee Department of Correction.

Courtesy of the Tennessee Department of Correction

Courtesy of the Tennessee Department of Correction Inmates at the West Tennessee State Penitentiary Tricor plant produce thousands of cloth masks for inmates and prison staff in early April, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention encourages widespread use of face coverings.

But Rich says the policy didn’t make sense to her. She didn’t want to risk treating a patient without proper protective gear while waiting on approval from higher-ups, only to find out later that she’d been exposed to the virus.

“I would like to state that guidelines are just that, they are meant to guide. They are not meant to be authoritative and dictatorial,” she wrote in an email to Centurion, the prison’s private health care provider.

Then Rich laid out seven conditions for her return, including a “daily decontamination process” for patient care areas, alcohol-based hand sanitizer and a workspace that allows for 6-foot spacing between patients and medical workers.

By early April, the Department of Correction had updated its official policy, to allow both inmates and staff to wear cloth face coverings. Widespread distribution at all state prisons began on April 6.

And in an email on April 20, a human resources representative told Rich that Centurion was working to meet her demands. But she said the company was “not able” to provide the level of disinfection or social distancing that she’d requested. And N-95 respirators would still be saved for treating COVID-19 positive or suspect patients.

As the virus has made its way through the prison in recent weeks, other medical staff have also walked off the job, out of frustration.

“Everybody was worried,” said a nurse who also took a leave of absence on March 31, when she was told she couldn’t wear her own N-95 respirator, which she’d brought from home. The nurse asked WPLN News not to publish her name, out of fear of retaliation from her employer. “They’re worried about losing their jobs and not having money to pay their bills. A lot of people have stayed there, working there, though they’re risking their lives, because they weren’t allowed to wear masks.”

A Centurion spokesperson said in an emailed statement that the company has been working closely with TDOC and local health agencies “to ensure our staff are prepared to manage the spread of the virus in correctional facilities.”

“We follow the most up-to-date and evolving guidance of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and public health officials for personal protective equipment (PPE) and adjust our policies as new information becomes available.”

The spokesperson said all Centurion staff now wear masks within correctional facilities, but did not specify if they were N-95 respirators or less protective face coverings.

TDOC told WPLN News that, as of last week, 16 employees had left the prison — 13 voluntarily. Eleven were correctional officers. Other staff members have temporarily been unable to report to work, after testing positive for the virus.

But the lack of preparation tells only a sliver of the story.

Just one day after Rich took her leave, TDOC announced the first confirmed case at Bledsoe. A contract employee had tested positive, and three inmates who had been exposed were quarantined.

That’s when Rebecca Phillips says the situation quickly escalated.

‘He was just stuck there’

“They started locking down other parts of the prisons, everybody telling a different story,” said Phillips, whose husband has been incarcerated at the Bledsoe County prison for about three years. “The Department of Correction saying, ‘No, nobody has the virus,’ where we have our loved ones, who are like, ‘Yeah, there’s, you know, people sick in my unit.'”

For the past few weeks, Phillips has been saving all of her husband’s letters and studying his words during their sporadic, five-minute phone calls, struggling to glean any information she can.

That got harder the third weekend in April, when TDOC started testing hundreds of inmates for the coronavirus. Phillips’ husband didn’t call for days. But while he was locked in his cell, he sent her a letter.

On April 19, he wrote:

“They sent in the bleach crew to bleach the ENTIRE unit. Walls, ceilings, floor and tables. They were told to do that several times a day. They came in and tested everyone in Unit 15 for COVID-19. And from what the guard said, the results are NOT good.”

By the next day, those results had started trickling in. More than 160 people had already tested positive. But inmates were left in the dark about who those people were.

Eight people told WPLN News that guards walked from cell to cell, placing signs on the doors to mark if someone inside had tested positive. But inmates — and even correctional staff — often weren’t told who inside the cell had contracted the virus.

“Officers might know an inmate’s status based on their housing assignments, but an individual’s health status is the private and legally confidential information of the inmate,” a TDOC spokesperson said in an emailed response to questions.

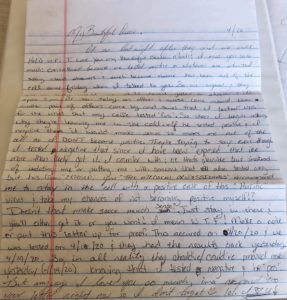

Courtesy of Tasha Lee

Courtesy of Tasha Lee An April 20 letter from Tasha Lee’s husband describes life during the coronavirus outbreak at the Bledsoe County Correctional Complex.

On April 20, Tasha Lee was anxiously waiting by the phone. Her husband, who is incarcerated at the Bledsoe County prison, hadn’t called in days.

“I was really concerned, because we went three or four days without hearing from him,” Lee says. “Then, we see on the news that they’re talking about mass testing and all these positive cases, so I was terrified that he was one that had it, and they weren’t going to let us know anything.”

Once the virus had started spreading, the prison was placed on “restricted movement.” TDOC says inmates were allowed to leave their cells each day for showers and phone calls. But loved ones say several days sometimes passed before they heard any news. And when prisoners were let out, they had only 15 or 20 minutes to wash up and call home.

While Lee’s husband was stuck in his cell, he sent her a letter. He said a pair of officers had come by and said he’d tested negative — but not his cellmate.

“He was asking about getting moved out, because his cellmate had it. And they told him that he was already exposed, so he probably had it. He would either get it or he wouldn’t,” Lee says. “He was just stuck there.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Correction confirms that cellmates have stayed together, even if one tested positive for the virus — as long as they’re asymptomatic.

But several days after testing negative, Lee’s husband told her on the phone that he’d woken up sore all over and coughing. She could hear the congestion in his voice.

“They’re telling the public one thing, but they’re doing the complete opposite of that,” Lee says.

‘It’s Just A Disaster”

On April 23, the number of cases inside Bledsoe jumped to 345. Then 576. And eventually 586.

By then, staff and inmates had started getting regular screenings and temperature checks. Both inmates and their loved ones were getting scared.

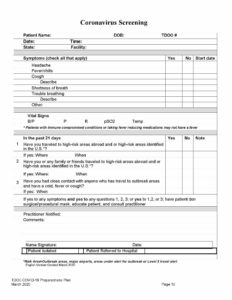

A questionnaire used to screen for COVID-19 at the Bledsoe County Correctional Complex.

“I’ve dreamed every night that my brother’s home with me and that’s he’s safe here,” says Andrea Smartt, whose brother has been incarcerated at the Bledsoe County prison for 23 years.

Patricia Gann, whose 28-year-old son is at Bledsoe, says she hasn’t slept well in weeks. When she talks to her son on the phone, she can sense the raw emotion on the other end of the line.

“I can tell he’s worried about it, but he won’t really express to me, because he doesn’t want Mama worrying about,” she says. “I can just hear the frustration in his voice.”

Late last week, TDOC reported that 580 inmates who had tested positive had completed their 14-day quarantine period and were symptom-free.

But two were in the hospital. And on Thursday night, a 78-year-old prisoner died.

“It’s just a disaster,” says Jacqueline Fagan, whose son was recently transferred to Bledsoe. When they spoke on the phone a few weeks ago, he told her at least six people in his pod had tested positive for the virus. Fagan is afraid her son will get sick, too.

“They’re closed in,” she says, her voice shaking. “They’re closed in with it, so they don’t have a chance.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Emma Rich is still waiting for the prison to meet her demands. She feels guilty that she can’t help her patients, like she’s abandoned them at the worst possible time.

But Rich says she won’t return until more protective measures are put in place — both for own safety and her patients’.

“They have undoubtedly made mistakes in their life. But none of these men or women were sentenced to death,” Rich says. “All of these people deserve and are legally required to get adequate healthcare, and part of adequate healthcare is infectious disease prevention and protection from outbreaks. And they weren’t provided that.”

This story has been updated to include a response from Centurion.

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.