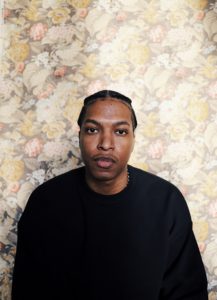

There are more paintings than furniture in Omari Booker’s studio in Nashville. His works are bursting with color, illuminating images of family and Black men. One painting, “The Black Bird,” captures his time in prison.

“That’s what a lot of days look like — sitting, reading a letter,” says Booker on a recent tour. “I wanted people to be able to feel like they were really interacting with someone in the space of a prison cell.”

Booker says his talents were born through a mix of education and life experiences, many of which were rooted in racism and engaging with police as a young Black male.

“This thing that became popular and hashtag-worthy in the past month … Is the reality I had since I was 4, 5, 6 [years old].”

Now, at 39, Booker is part of a long line of Black artists whose works respond to injustices, from sculptor Augusta Savage to jazz legend Miles Davis.

In the 1930s, Savage rose to prominence for blending art with racial issues. One piece, The Harp, was inspired by “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often referred to as the Black national anthem. Before that, Savage was known as a self-made Black woman who paved the way for the Harlem Renaissance.

Then there’s Davis, whose now acclaimed 1971 soundtrack album paid tribute to Jack Johnson, the heavyweight fighter whose win against a white boxer sparked a series of race riots in 1910.

Black music, especially hip-hop, has become an inspiration for Booker and the way he views his paintings.

“People might look at a Mos Def or Common and Talib Kweli. You could put those artists in 2020, [along with] all of their albums from 1998,” says Booker. “Or take a Marvin Gaye from 1970, all of that is just as relevant today because [protesting racism through music] is such an old problem.”

But in Nashville, some artists are taking a new approach to protest music. They’re also seeking to use their platforms to do even more for the cause.

‘Black Music Matters’

At a recent protest on Music Row, billed as “Band Together For Justice,” Nashville’s Black music advocates sought to bring light to discrimination in the city’s music industry while shedding light on police brutality.

“There’s hip-hop, pop, R&B, soul, funk, gospel, jazz … right here in Nashville,” says Thalia Ewing, founder of Nashville Is Not Just Country Music, an organization that works to make Nashville an equitable music scene.

Thalia Ewing

For Black musicians, fighting racism and brutality can track back to slavery. One example is the spiritual “Wade In The Water,” a song believed to be used by abolitionist Harriet Tubman while leading men and women to freedom.

In today’s era, Black music still represents a fight for freedom, with artists using it as a motivation to use their platforms to do even more for the cause. For some that means becoming involved in public protests or politics.

“My cousin, Daniel Hambrick, was shot and gunned down two years ago by Officer Andrew Delke. We’re still fighting for justice for that,” says Samuel Hambrick. “I’ve been grinding since day one and hopefully we’ll get justice soon enough. Until then, I’ll keep marching, protesting and doing what I have to do.”

Hambrick’s been active in the hip-hop community since childhood. He says he’s happy to see other artists coming out to rallies, because he sees Black music and protests going hand-in-hand.

“On the music side and the political side … this couldn’t be a better time to incorporate what’s going on in the country today,” Hambrick says. “As far as … Black Lives Matter and getting justice, equality and unity, everything is coming together [because of Black music].”

Doing More For The Cause

Nashville hip-hop artist Mike Floss is one of the many Black musicians who’s experienced police brutality firsthand.

“I know what it’s like to be assaulted by the police and end up getting arrested and catching charges for assaulting them — when all I was doing was standing outside,” says Floss.

In 2017, Floss, who often raps on bass-filled but smooth beats, released “Black Wildflowers” as a candlelight vigil for victims of police brutality. He also released “Peach Soda,” which hints at the Black experience when it comes to policing.

Mike Floss

He says despite his own encounters with police, he’s been fortunate to have never been seriously injured. He also says he’s been lucky to have never been caught up in the criminal justice system.

“To come out of those experiences and be able to talk about them is definitely what I think about a lot lately,” says Floss. “It could have went a lot worst.”

Floss says he’s at a point now where he doesn’t quite know what to do to end racism, but he knows that he wants to do more.

“When it’s hip-hop, we’re pretty much just speaking about [how] we don’t like the police,” says Floss. “Maybe we can start talking about the process of how to change this system.”

He says the next step may be for artists to get involved in politics and put people with ties to the community in city council seats.

But he also says Black men need to do a better job of protecting and elevating the voices of Black women who want to lead the movement for racial justice. Floss says the more voices that are involved, the better the changes will be for everyone.

“I think their voices are massively important,” says Floss, “and oftentimes more valuable than ours.”