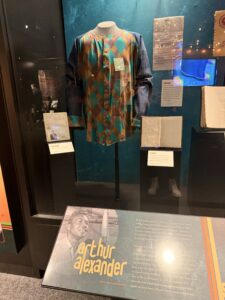

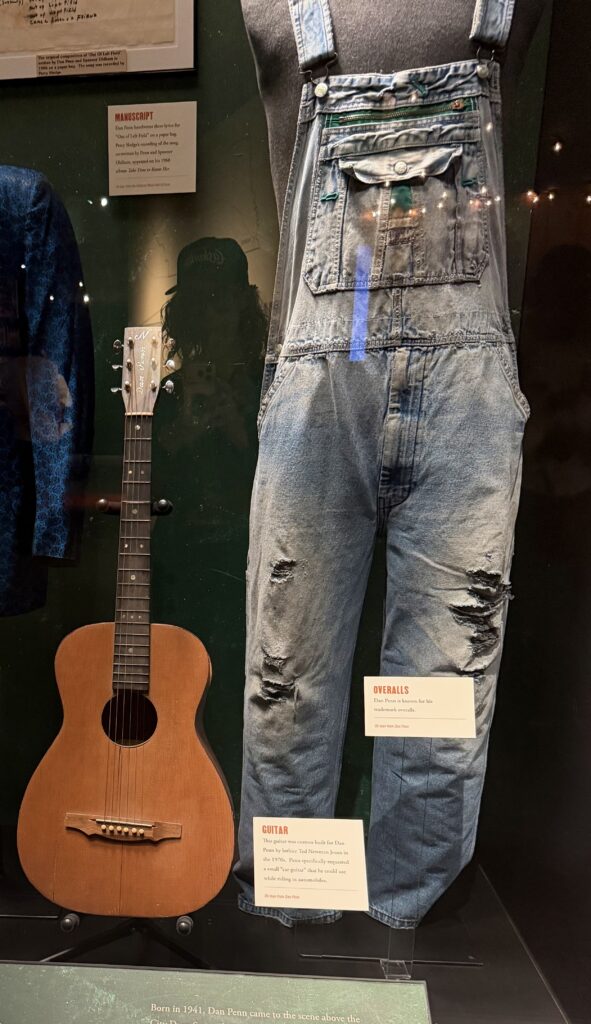

Just around the first corner of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s new Muscle Shoals exhibit, a pair of worn bib overalls hangs behind glass. The night the exhibit opened, the garment’s 84-year-old owner, Dan Penn, ambled around in a fresh pair.

As one of the guests of honor, Penn’s contributions to the history on display weren’t limited to downhome denim.

“Well, I wrote a few songs and I sang a little and I produced records,” he deadpans with his trademark folksy economy.

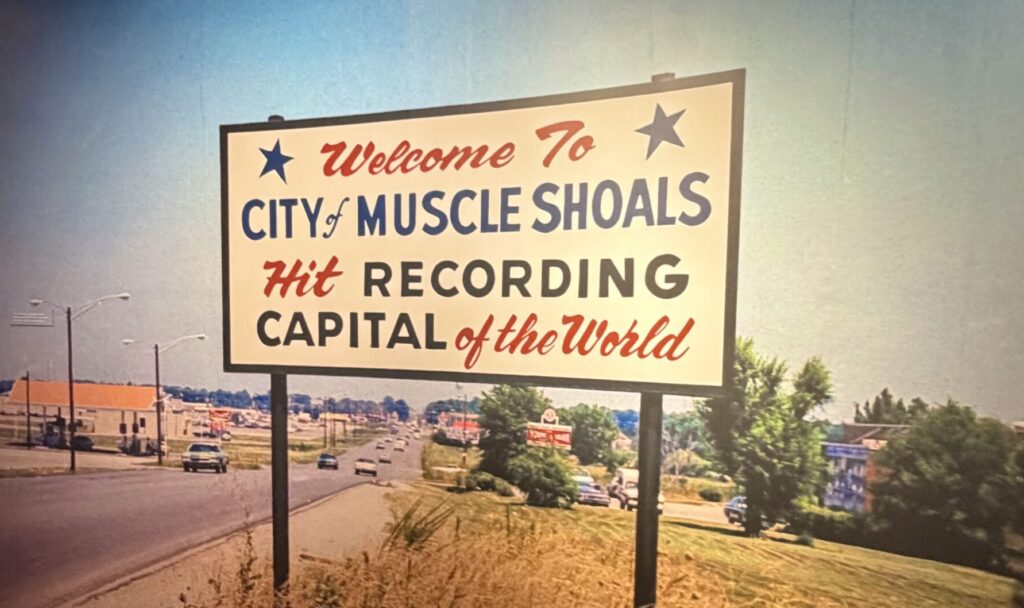

In reality, the scene where he first made his mark would wind up with a road sign that made a far grander claim to fame: “Welcome to the City of Muscle Shoals, hit recording capital of the world.”

Before all of that music-making, Penn plowed the family farm in rural Alabama. After showing some songwriting promise in high school — which led to a rockabilly cut with Conway Twitty before Twitty set his sights on country music — Penn was hired by a local guy named Rick Hall who’d decided to build a studio called FAME in a former tobacco warehouse. (That was technically the second FAME location, since Hall had gone in with business partners Billy Sherrill and Tom Stafford on a spot above a drugstore in neighboring Florence the year before and coined the acronym that stood for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises.)

“And it was five years there that I felt inadequate, like I wasn’t getting anywhere,” Penn recalls. “We had a few cuts during that era, but it was sparse. I wondered about going back home.”

Then Penn and his keyboard-playing buddy Spooner Oldham came up with “I’m Your Puppet,” which became a 1966 hit for the R&B duo James & Bobby Purify.

After that success, Penn reassured himself, “ OK, you do write songs.’ ”

Making it up as they went

Penn was a white boy from the deep South who wanted to make R&B and had little use for country music, and in the Muscle Shoals recording scene that also served as a pivotal workspace for Black recording artists with country affinities, those leanings fit right in. In many ways, the music-makers played across and complicated the color line between genres.

That line had been an artificial creation in the first place, imposed generations earlier on Black and white performers in the South who’d developed stylistically wide-ranging musical repertoires through the natural exchange of influence, as well as the grotesque cultural appropriation that was blackface minstrelsy. American commercial recording was founded on the segregation of musical sensibilities into “race” and “hillbilly” records, the former, in essence, selling Black blues performances to Black audiences and the latter white old-time numbers to white listeners.

Not that the Muscle Shoals hopefuls had any sort of lofty, culture-shifting aims at the start, notes R.J. Smith, one of the exhibit’s curators: “They were like, ‘Well, we can work in the aluminum factory or we can find a way to make a hit record.’ I know which is more fun.”

And since FAME was the first professional recording studio in the entire state of Alabama, says Smith, “they had the gift of making it up as they went. There was nobody there to tell them they were doing it right or wrong.”

The very first hit made at FAME, years ahead of “Puppet,” belonged to local singer-songwriter Arthur Alexander. The exhibit’s ci0curator, Michael Gray, describes Alexander as “a Black singer who was working with white musicians, and kind of set that template for country soul. He was part R&B, part country storytelling and putting it together.”

Ultimately, Alexander enjoyed more influence than success. After struggling for years to make a decent living from music, he resorted to driving a bus. His songs, on the other hand, have been covered by white rock stars far more famous than him, a list that includes the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and, on the night of the exhibit’s opening reception, contemporary Muscle Shoals export Jason Isbell.

After Alexander passed years back, Isbell had paid his respects by playing a benefit show to raise money for the elder artist’s headstone. “It’s a shame that such a thing needed to happen,” Isbell reflects.

In his Alabama youth, Isbell came up jamming with Muscle Shoals musicians who were still around, including bassist David Hood. Later, Isbell would be absorbed into the literary Southern rock outfit Drive-By Truckers, co-founded by Hood’s son Patterson, then achieve significant renown as a solo singer-songwriter and bandleader, and it was then that he learned the power of that association. “Anytime I met my heroes, if I mentioned where I was from,” he says, “then we had something to talk about. Because everybody wants to talk about these musicians that made all this happen.”

Drawn to the sound

The Muscle Shoals lore that Isbell’s referring to grew when an executive from New York-based Atlantic Records began bringing artists down to Alabama to get the lean, earthy sound that had become a desirable local specialty.

At one 1967 session, already half a dozen years into her secular recording career, Aretha Franklin shook hands with the white studio band, known as the Swampers, sat down at the baby grand piano and cut her first No. 1 hit, “I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You).”

“That session really did transform her career, and the town,” says Gray. “In the seventies just everybody was flocking to Muscle Shoals.

He starts reeling off names: “Paul Simon and Bob Dylan and the Staple Singers…”

Atlantic also sent Bettye LaVette, a no-nonsense soul singer from Detroit. Her background had exposed her to R&B, gospel, pop and country alike, and she felt like she held her own working with the Muscle Shoals musicians, who were young and hungry like her.

“In the studio,” she says, “it was limitless. You could do whatever you wanted to do. But it’s the commercial side of it that’s the thing.”

LaVette’s talking about the barriers that Black artists faced in the industry, even when they had the chance to transcend stylistic limitations. Her Muscle Shoals album got shelved for decades, finally coming out in 2006. And a single she hoped would become a pop hit was beat out by a white artist’s version of the song.

“When you hear me sing,” she emphasizes knowingly, “what you hear is that I am still upset about all of those things.”

It wasn’t just LaVette whose commercial prospects were eclipsed by her white counterparts, as scholar Charles Hughes makes clear in his 2015 book “Country Soul.” But at the same time, Muscle Shoals also represented valuable opportunity.

Francesca Royster, an academic who places her work in conversation with Hughes’, wrote about another Black singer in the exhibit, Candi Staton. And during their interviews, Royster was struck by the way Staton credited her Muscle Shoals albums with launching her solo career. “That work that she did on that in that first album and subsequent albums as well,” Royster notes, “allowed her to make a living as a professional musician in a way that I don’t think she would have otherwise.”

Royster points out that Staton spent those sessions recording an array of country and soul material that showcased her as a multidimensional artist. And so does the buckskin stage costume of Staton’s that’s now on prominent display in the museum.

“I just love the way that an aspect of the cowboy is part of her image as well,” says Royster. “But also in her own elegant and funky way, like always, a hybrid of things.”

Long before Beyoncé reinterpreted Dolly Parton’s classic “Jolene” on “Cowboy Carter,” Staton recorded her own fierce version of the song in Muscle Shoals in 1974, just a year after Parton. Royster speculates that Bey may have found some inspiration in Staton’s rendition, and its tough, confrontational tone.

Staton is better known for her later gospel, disco and dance recordings, so Royster also hopes the exhibit, and the events and conversation around it, will draw more attention to Staton’s foundational work in country soul. “A chance to put her back in the story as an important force,” Royster says.

And Smith, its co-curator, sees lessons for today in all this complex history: “It’s where are in country music, where people talk about, ‘Is that person really country? Is Beyoncé country?’ It gives us a chance to lead people into the museum to think about people coming together at a specific time and place from across racial lines, cultural lines, parts of the country, and sitting in this space and making amazing music together.”