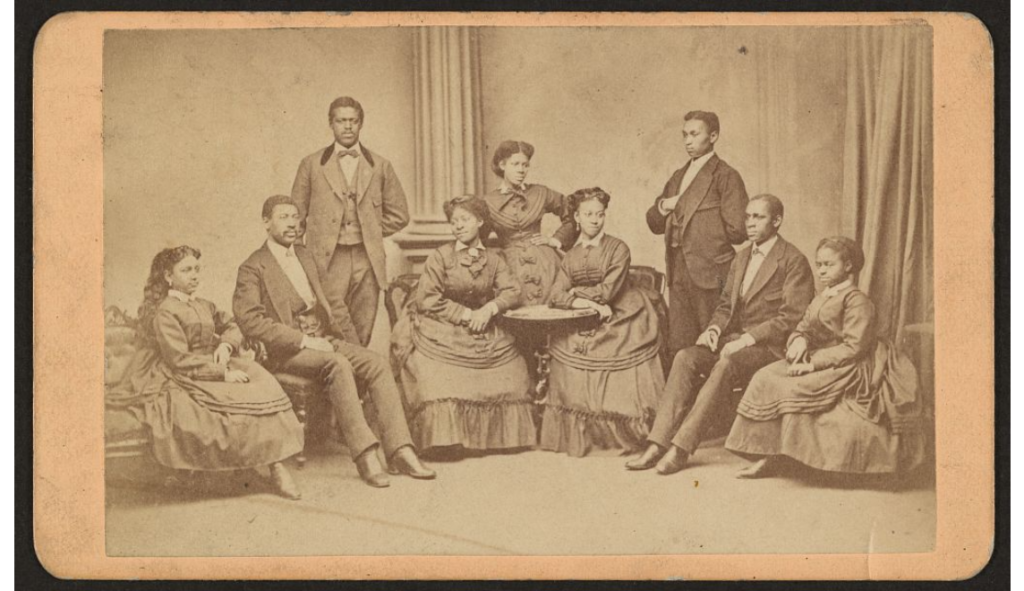

When the Fisk Jubilee Singers set out to travel across the United States they eventually grabbed audiences’ attention with the songs of their faith. From the first notes of Steal Away, they had the attention of the world.

Dr. Steven Lewis, a curator at the National Museum of African American Music, describes how these songs truly did evolve within communities here in the United States, starting in the 19th century. But, as he points out, “probably there were people singing before them.”

No genre of music has a distinct moment of beginning or end, but rather a development across time and circumstances. But the influence of Black church music permeates every genre of vernacular music in the United States, even today. In an interview last April, Dr. Lewis brought me on a musical journey through time, tracing a direct line from Spirituals to the blues, jazz, and gospel music.

Answers are edited for clarity and length.

How, by sound, would you distinguish a Folk Spiritual like you’d find in a religious service from a Concert Spiritual, like what we hear from the Fisk Jubilee Singers?

Folk spirituals are characterized by a vocal style that features improvisation, the expressive use of moans and other kinds of inflections, ornamentation of the melodic line. [They have] heavy use of call and response between, say, a solo singer and a group. Often songs like the folk spirituals would be performed in conjunction with a ceremony like a Ring Shout, which is still practiced in places like coastal South Carolina and Georgia.

Their style is very distinct from the style that would develop later in the 70s, which takes that kind of repertoire, takes some elements of the distinctive African-American style and transposes them into kind-of a European choral context.

That’s where you get the Jubilee Singers. You take that folk tradition and then you meld with the European concert singing tradition. And then you get, of course, these great solo vocalists like Roland Hayes and people like that.

How do spirituals connect to blues?

I think the best way to understand that development is you have the early blues singers, say in the late 19th century, who themselves would have grown up in and participated in religious services. These are people who are coming up in African-American communities all over the rural south. They take that distinctive singing style that is associated with the folk spirituals–that is the the vocal ornamentation, the expressive use of moans and and other types of devices–and transpose that to a new secular context that is also informed by European traditions like ballad singing and things like that, which are also all over the south at the same time because of, say, the Scotch, Irish population and other people.

It’s that expressive tradition that develops with the spirituals in terms of the way that one would sing, the way you use your voice. And then that is kind of applied to a new context beginning around the [18]80s and 90s. And so, that kind of becomes the foundation of blues singing. And by extension, you know, all of the things that come after that, like in R&B, soul singing and so on. And so if you trace those all the way back to the kind of late and mid 19th century, you do end up back at the spirituals, essentially.

And how does that relate to the evolution of jazz?

Buddy Bolden

It’s a similar process. You have musicians like Buddy Bolden, who was arguably the first leader of the first jazz band. He’s somebody who came up in the church – there’s accounts of him, you know, attending Baptist church services in New Orleans. And we know that in his band, not only did he play pop songs and folk songs of the day, they would adapt ragtime songs in this new style that became known as jazz. He also performed hymns and spirituals and things like that.

There’s a direct connection there because these musicians are in the church. You also have elements of the actual repertoire show up in the repertoire. Early jazz songs like Down by the Riverside, for example: that is a traditional spiritual. It’s also a song that continues to be played by New Orleans jazz bands – the traditional ones anyway.

Another important element of that connection is the importance of the jazz funerals, where you have bands that would play kind of mournful songs, walking the body to the graveyard for burial. And on the way back, they would famously play very upbeat and celebratory music. Kind of acting out the idea that one should cry at the birth and rejoice at the death.

In those kinds of traditional ceremonies, which are also one of the important roots of jazz, you have this very important role played by the traditional religious songs, you know, these things that come out of that folk spiritual tradition.

There are other musicians: Bunk Johnson was several years younger than Bolden, but he was roughly a contemporary. He made a lot of recordings in the 1940s in particular. So they recovered him as an elderly man and got him out of retirement.

Bunk Johnson

Down By The Riverside was in John W. Work II’s collection Folk Songs of the American Negro, right?

And actually Bunk Johnson recorded down by the Riverside.

It was one of those songs that became a standard, and that song was a spiritual first. So that spiritual repertoire gets reinterpreted and continues to pop up and all these different contexts. So that’s so that covers that’s where jazz kind of comes out of the blues.

It’s such a similar line.

Exactly. They’re very close. They’re really intertwined in really important ways. It’s hard to make a firm distinction because you have people like Bessie Smith, who is performing as a blues singer, but is also singing songs that aren’t blues and singing them with jazz musicians, which would make her a jazz singer as well.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers and the early blues musicians and the early jazz musicians are all coming out of the common roots of the folk spirituals. When the Jubilee Singers are making their first tours of Europe, like in the mid late 1870s, the early blues is probably emerging at the same time in the and southern communities, including in Tennessee. There’s so much of this amazing flourishing of musical innovation in the decades following the Civil War.

I know we’ll be looking to churches next, but while we’re on the topic of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, what about academia?

Because of how financially successful the Fisk Jubilee Singers were, you have a lot of strictly show business groups. But you also have that historically black colleges, you have other groups like Hampton has a group that comes up pretty soon afterward. Tuskegee has an excellent group. Morehouse, of course, the Glee Club.

As you move further into the 20th century those groups become the big groups that are conserving that element of Black musical heritage, where the rest of African-American religious music has developed in other ways.

That’s a good segue to gospel music.

This is when gospel kind of branched off from the spirituals, beginning in the 1920s. You have people like Arizona Dranes, who is probably the first person to record gospel music coming out of the Pentecostal tradition.

Thomas Dorsey

Thomas Dorsey, who is extremely important and is known as the father of gospel music. You have artists like them who are taking, again, that folk spiritual tradition–which is still very important in Black religious worship in the early 20th century–and introducing elements from more contemporary styles. So introducing elements of jazz, elements of blues.

How would you say that manifested itself early on? Was it adding the piano and the drums?

All of the above. It’s significant that Arizona Dranes is coming out of the Pentecostal tradition because churches in those denominations were some of the first to adopt musical instruments at a time when a lot of more conservative churches were reluctant to bring instruments into the sanctuary..

Again, you have this mingling of vernacular music with the spiritual tradition. And so when you listen to someone like Arizona Dranes, who did record pretty prolifically, actually, you have her singing religious lyrics, but then the way she plays the piano is actually coming out of sort of ragtime and blues piano of the early 20th century. And so that’s she’s the first example on record of that type of what would develop into gospel music in the decades after that.

By the time you have Thomas Dorsey recording, he really becomes important in the nineteen thirties and forward. You have somebody who is consciously kind of outwardly saying, ”I came out of this kind of blues and jazz background, I’m bringing that stuff into gospel music.”

Gertrude “Ma” Rainey

This is still a religious music that still is serving this important ceremonial cultural function, but it also is drawing on these other styles that are not religious. And again, a lot of that is because before he became a gospel musician, he was a blues pianist known as Georgia Tom, because he was from Georgia. And he played with people like Ma Rainey.

He never really loses that blues and jazz influence. He just again transposes elements of that style into a religious context, which is something we see over and over again in the history of African-American music in particular. That kind of fluidity of the sacred and the secular.

Eventually Ray Charles does this in the opposite direction. Thomas Dorsey takes the secular and brings it into the religious context. Ray Charles gets into a lot more trouble maybe by taking the religious upbringing into a secular context.

Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson is another great example of that important influence that secular music had on the development of gospel music. Because Mahalia Jackson is probably one of the most important of the descendants of Bessie Smith. Mahalia Jackson’s singing style comes in large part from the admiration that she had for Bessie Smith’s music. And but she, Mahalia, did not want to sing other than for God and in this religious context.

So you have the power of Bessie Smith’s voice, the ability to to really masterfully use these techniques of ornamentation and improvisation, and the ability to engage an audience in a way much like you’d see in a religious service. And so if she takes that and then applies it to what will become gospel music. And remember, Bessie Smith, herself as a blues singer, is also inspired by earlier black religious traditions.

It’s circular.

Gospel continues to evolve as a truly American sacred music tradition. Meanwhile rhythms and harmonic patterns from jazz and the blues permeate popular genres, where the links to R&B, disco, and hip-hop lie. Rock, country, and even classical music also owe a great deal to this influence – with the 12 bars of the blues, the twang of a banjo, and the orchestras imitating what composers once heard in jazz clubs. As Dr. Lewis said, “it’s circular.”

These connections are on full display at the National Museum of African American Music in downtown Nashville, less than 3 miles from Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall – the school that spirituals built.