Reporting Highlights

- A “Valid” Threat: Schools must use threat assessments to determine if a threat of mass violence is “valid,” but they often carry them out inconsistently.

- No State Transparency: Tennessee is supposed to track how effective schools’ threat assessments are, but the state does not release that information to the public.

- Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Experts say it’s dangerous for schools to expel students without plans to follow up or address behavioral concerns.

The day after a teenager opened fire in a Nashville high school cafeteria early this year, officials in the district scrambled to investigate potential threats across their schools. Rumors flew that the shooter, who killed a student before turning the gun on himself, had accomplices at large.

At DuPont Tyler Middle School, the assistant principal’s most urgent concern was a 12-year-old boy. James, a seventh grader with a small voice and mop of brown hair, had posted a concerning screenshot on Instagram that morning, Jan. 23. He was arrested at school hours later and charged with making a threat of mass violence.

The assistant principal had to complete a detailed investigation called a threat assessment, as required by Tennessee law. First, she and other school employees had to figure out whether James’ threat was valid. Then, they had to determine what actions to take to help a potentially troubled child and protect other students.

Threat assessments are not public, but the district gave ProPublica a copy of James’ with his father’s permission. School officials did not carry out the threat assessment properly, according to experts who reviewed it at ProPublica’s request. Instead, the school expelled James without investigating further and skipped crucial steps that would help him or protect others. (We are using the child’s middle name to protect his privacy.)

The way school officials handled James’ case also exposes glaring contradictions in two recent Tennessee laws that aim to criminalize school threats and require schools to expel students who make them — with minimal recourse, transparency or accountability.

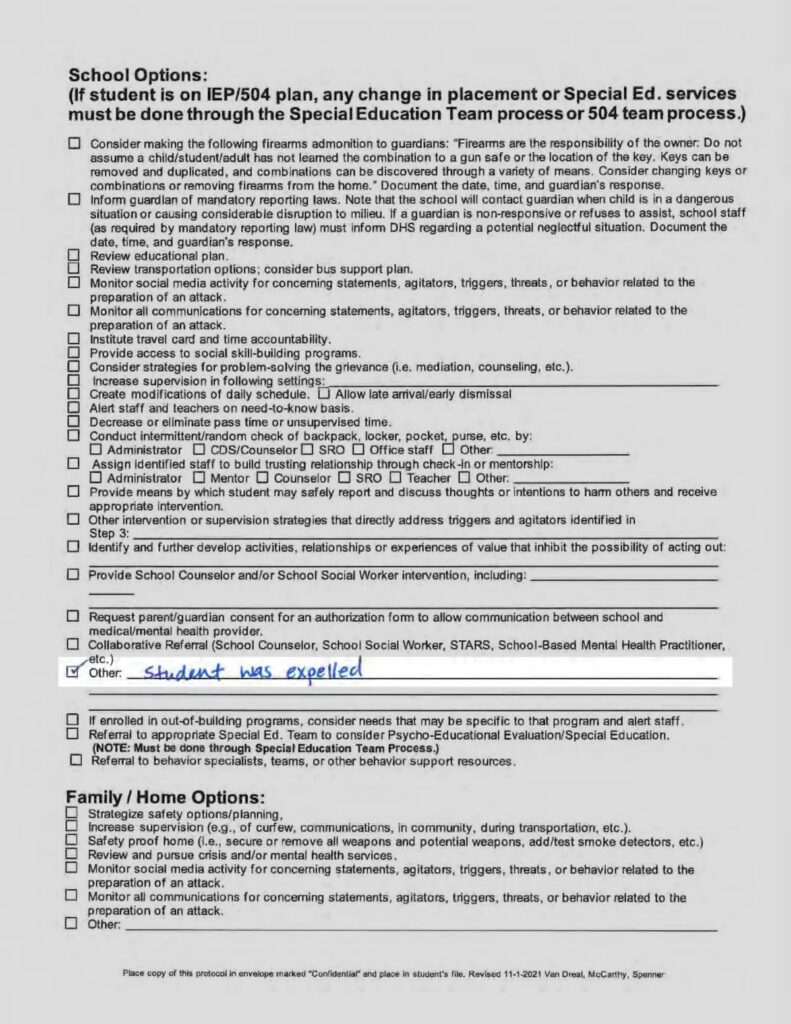

One obvious issue in the threat assessment, according to the experts, appeared on Page 20. That page features a checklist of options for how the school could address its concerns about James, including advising his parents to secure guns in their home and ensuring he has access to counseling.

Schools should take steps like these even when a student is expelled, according to John Van Dreal, a former school administrator who has spent decades helping schools improve their violence prevention strategies. Officials at James’ school opted for none of the options they could have taken. Instead, the assistant principal wrote under the list in blue pen, “student was expelled.”

“That’s actually about the most dangerous thing you can do for the student,” Van Dreal said, “and honestly for the community.”

Van Dreal’s name appears in tiny print at the bottom of each page of James’ threat assessment, because he helped the school district set up its current process. After ProPublica shared details about James’ case, Van Dreal said, “What I’m hearing is probably more training and more examples are needed.”

Nashville’s school district does not collect data on how many threat assessments it does or how many result in expulsions, according to spokesperson Sean Braisted. “The goal is always to ensure the safety and well-being of all students while addressing incidents appropriately,” Braisted wrote. He later declined to answer questions ProPublica asked about James’ case, although James’ father signed a privacy waiver allowing the school to do so.

Tennessee schools must submit data to the state on how effective their threat assessments are — but the state does not release that information to the public. School districts are required to get training on threat assessments, but lawyers and parents say they often carry them out inconsistently and use varying definitions for what makes a threat valid.

Two recent contradictory Tennessee laws make it even harder to handle student threats. One mandates a felony charge for anyone who makes a “threat of mass violence” at school, without requiring police to investigate intent or credibility. The other requires schools to determine that a threat of mass violence is “valid” before expelling a student for at least a year.

James’ alleged threat was a screenshot of a text exchange. One person said they would “shoot up” a Nashville school and asked if the other would attack a different school. “Yea,” the other person replied. “I got some other people for other schools.” The FBI flagged the post for school officials and police. James told school officials that he reposted the screenshot from the Instagram page of a Spanish-language news site.

The Tennessean published a story in April detailing James’ arrest and overnight stay in juvenile detention. The story, and the ones ProPublica and WPLN published last year on other arrests, shows how quickly police move to take youth into custody.

Schools in Tennessee are supposed to follow a higher standard than police when it comes to investigating threats of mass violence: They’re supposed to determine whether a threat is valid. For instance, in Hamilton County, a few hours southeast of Nashville, school officials chose not to expel two students even after police arrested them for threats of mass violence, ProPublica and WPLN previously reported.

Yet when James’ father appealed his son’s expulsion at a March school district hearing, the assistant principal said repeatedly that James had to be expelled simply because he’d been arrested. “We did not investigate further,” she said. James’ father shared an audio recording of the hearing with ProPublica.

James, who turned 13 in February, is small for his age, still awaiting the teenage growth spurt of his three older brothers. At the hearing, his voice was soft but assured as he explained what happened. He said he understands why he shouldn’t have posted the screenshot. But he said he wanted to warn others and feel “heroic.”

Melissa Nelson, a national school safety consultant based in Pennsylvania who trains school employees on managing threats, reviewed James’ threat assessment at ProPublica’s request and concluded that “this is gross mismanagement of a case.”

“This tool has not been used as intended,” she said. “They didn’t do a behavior threat assessment. They filled out some paperwork.”

After the police took James away, assistant principal Angela Post convened a team of school employees to decide whether to expel him. They used a threat assessment form that Van Dreal had developed, one of the most commonly used across the country, to guide them on how to respond.

According to Van Dreal, Metro Nashville Public Schools is in an early phase of using the form, and its staff have flown to Oregon at least once to learn from his consulting group.

Van Dreal tells school officials to use the threat assessment to collect information about a student in trouble and address behavior that could signal future violence. If school officials worried that James was planning an act of violence, they should have pursued some of the many options outlined in the threat assessment to get him help and protect the school from harm.

Instead, they chose none of those options.

Experts said that is one of the biggest mistakes school officials make. “Even if a child is expelled, what I always train is: Out of sight, out of mind doesn’t help,” Nelson said. “Expelling a child doesn’t deescalate the situation or move them off the pathway of violence. A lot of times, it makes it worse.”

School officials also failed to seek out more information that could have helped them figure out whether the threat was valid. Post checked a box acknowledging that she hadn’t notified James’ parents of the threat assessment. She wrote beside it, as an explanation, “student was arrested and expelled.” On a line asking whether James had access to weapons, Post wrote that the threat assessment team did not know.

Interviewing parents is a crucial part of the process, said Rob Moore, a Tennessee psychologist who has helped schools conduct threat assessments for more than two decades. “When you sit in that room with those parents and you collect data from them, you really get a sense of things that teachers would never know, that the administrators would never know.”

Although school officials did not opt to investigate further or to monitor James, the threat assessment indicated they had concerns he may pose a threat. In response to a question about whether James’ caregivers, peers or staff were concerned about his potential for acting out aggressively, Post checked yes and wrote, “He has little to no supervision in discipline structures at home but might think he could get away with it.”

And although James told school administrators he was not a participant in the text thread he shared on Instagram, Post wrote that he had indicated a plan and intention to harm others. “See attached image. Shows location, intent to harm, targets and date,” she wrote, referencing a screenshot of James’ Instagram post. She also wrote that he had a motive: “The post indicated that he was being made fun of. See attached image.”

The threat assessment included questionnaires from James’ teachers; three out of four said they did not have concerns about potential aggression. One teacher, who taught James social studies, cited his disciplinary history: using racial slurs, fighting another student and “researching racially motivated things” on the school computer. “Dad seemed disengaged in conference & somewhat unaware of the child’s school or social or personal issues,” she wrote.

James’ dad and stepmom did not know that the threat assessment accused them of lax supervision at home. That’s because they didn’t even know the threat assessment existed until ProPublica told them about it, more than a week after it took place.

Upon reading the document, their first emotion, after shock, was anger. They said they hadn’t known about the incident with the racial slur, and it was not directly referenced in a copy of James’ disciplinary history. But they felt upset at the insinuation that they had not been involved in James’ life. “We’ve been asking for help, for grades, tutoring,” his dad, Kyle Caldwell, said. “And we really didn’t get any.”

James said that in early September, his social studies teacher taught the class about World War II. He said the teacher didn’t answer enough of his questions, so he started searching online. The school flagged that he had looked up swastikas. “I didn’t know much about it,” he said. “That’s why I searched it.”

As part of his discipline, the school prohibited him from using its computers. His stepmother, Breanne Metz, shared emails she sent to James’ teachers explaining she and Caldwell were worried about his grades and wanted to help him catch up.

James had been struggling with his parents’ contentious divorce; after his mom lost custody of him, he hadn’t been able to see her in months. Worried, his dad and stepmom arranged for him to see a school counselor. James said the counselor tried to connect with him through their mutual love of video games over about five sessions, which was nice, though “it didn’t really help.” Post wrote in the threat assessment that James had “disclosed confidential information to the school counselor that would support a feeling of being overwhelmed or distraught.”

Then James lost his best friend: Lieutenant Dan, a three-legged pitbull-lab mix named after a character from the movie “Forrest Gump.” Dan joined the family when he and James were both 1, and he died of cancer last November. As James describes it, he was at capacity with the emotions he was dealing with, and his dog’s death was the tipping point. “When someone you love or something you love for your whole life passes away, you can’t hold it,” he said. He sat in class feeling sad and exhausted.

Records show school staff talked with James’ parents about his attendance at school and he was disciplined for not complying with an unspecified request. Then in mid-December, he began a fight with another student, who had been “horseplaying” with him “off and on” and went too far, according to the school report. The following month, he was arrested and expelled.

In the days after the arrest, Caldwell considered hiring a lawyer. Reading the threat assessment “added the urgency” for him to finally make the call. “The puzzle pieces weren’t coming together in their story,” he said. “It really looked like they were going to try to be sweeping their stuff under the rug.”

In mid-March, James sat at the oval table in the district conference room next to his father and across from assistant principal Post. He wore a gray vest over his T-shirt in preparation for an appeal hearing that would determine whether he would be allowed back in school. It had been nearly two months since he had set foot on district property.

Caldwell brought his private lawyer, a rare resource for a school hearing. He showed up that morning nervous but eager to make his case directly to school administrators. The public rarely gets insight into what happens at a school appeal hearing, but Caldwell shared an audio recording with ProPublica.

Post started by reading aloud the social media post that landed James in trouble, stumbling over the shorthand and unfamiliar internet slang. Then, it was James’ turn to speak for himself.

Lisa Currie, the school district’s director of discipline, asked him to explain why he had reposted the screenshot of the texts. “You do understand that once you reposted them from somewhere else, it gave the appearance that this was a conversation that you were having?” she said.

“I just wanted to let people know, feel heroic,” James said. “I didn’t want more people to get hurt.”

Over the next 40 minutes, Caldwell’s lawyer questioned Post about the process the school used to determine whether James should be expelled. When he pressed her for direct responses, Post repeatedly said that law enforcement and not the school held the primary responsibility for investigating the threat. Although the law requires schools to use a threat assessment to determine if the threat is “valid,” Post and her team based the expulsion entirely on the police’s arrest.

Once local police take over a case, she said, “then it’s not really our investigation anymore.”

“Was it your assessment at the time that he wrote this statement, like physically typed it out on a computer and posted it?” the lawyer asked.

“We did not make that determination,” Post said.

She said school staff did not look deeply through James’ disciplinary history as part of the threat assessment. “That’s not necessarily the purpose of the threat assessment,” she told the lawyer. Because James had been expelled and arrested, “there would not be a reason to be concerned about the return of a student.”

Currie indicated that Post’s approach was supported by district leaders. “The purpose of the threat assessment is to determine appropriate supports and interventions around the students while they’re in the building,” she said. Post and Currie did not respond to ProPublica’s requests for comment or to written questions.

Post told the lawyer she couldn’t remember whether school staff investigated the origin of the original threat.

“So if there was an actual threat made and somebody else authored this threat, then we don’t know who that is. Would that be a fair statement?” the lawyer asked.

“That is possible,” Post responded. She said James didn’t initially say that he had shared the post to warn others and it wasn’t her place to decide whether he intended to make a threat. “I don’t want to think, ‘Oh, he’s not going to do that.’ And then something just like the previous day happened,” she said, referring to the Antioch High School shooting. Once James was arrested, “it’s in MNPD’s hands,” Post said, referring to the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department.

The lawyer asked Post to explain whether the threat assessment could ever have changed school officials’ decision to expel James: What if school officials found out that the threat was not valid? “Had y’all come on information that he had not written these texts,” he asked, “would it have changed the punishment?”

“We would have had to let our [school resource officer] know and they would have had to go through the MNPD channels,” she said.

“You did not at that time know whether he wrote those text messages or not?” the lawyer asked again.

“Correct,” Post said.

Then, it was Caldwell’s turn to speak. He criticized the school’s decision to leave him out of the initial disciplinary process. He would have explained to James why he should go through “appropriate channels” to report a threat instead of posting it on Instagram. “As a dad,” he said, “there was a teachable parent moment that I didn’t get to have.”

As the hearing came to a close, Currie told Caldwell to expect a decision soon.

The arrest and expulsion cleaved James’ life in two. He now begins many sentences with the phrase “before everything happened.” Before everything happened, he would ride his bike with his brothers and friends to explore the forested land and abandoned houses in the surrounding neighborhoods. They found all sorts of strange garbage: a fire engine’s license plate, wooden pictures of “demonic rituals,” a dentist chair adorned with rusty handcuffs.

He was able to come home from his night in detention in exchange for agreeing to pretrial diversion with six months of court supervision, a common outcome for students charged with threats of mass violence. While under supervision, he wasn’t allowed to use the computer or phone unsupervised by an adult and was mostly restricted to the streets around his house. “It’s a big neighborhood, but once you get used to it, it’s small,” he said.

The court recently lifted his supervision, earlier than expected. Because he had completed the terms of pretrial diversion, his case was dismissed.

His parents declined Metro Nashville Public Schools’ offer to enroll him in the local alternative school, which primarily serves kids with disciplinary issues who were suspended or expelled from their original schools. Instead, they enrolled him at an online public charter school; he starts in the fall.

As James waited to hear the result of the expulsion hearing, he followed the schedule his dad and stepmom created for him — less a rigorous academic curriculum than a routine to keep him occupied while his stepmom takes calls in her home office. He gets most excited about the hands-on activities, like building and painting the model F-15E fighter jet his dad bought him online.

One night in early April, tornadoes touched down just outside Nashville. James, his five siblings, and two dogs huddled with Caldwell and Metz in the windowless laundry room; the kids wore helmets in case of falling debris. When they got up the next morning, groggy but unharmed, Caldwell checked the mailbox: A letter from the school district was inside.

District officials had reviewed the information from the hearing and determined that “there was not a due process violation of MNPS’ expulsion process.” James was still expelled. Caldwell had prepared his son for this outcome so that he wouldn’t be devastated. James would later joke that the storm had delivered the bad news.

The letter gave the family the option to escalate the appeal through the district process. But the odds of winning and the costs of retaining the lawyer made the effort feel futile. The more the family fought back, the more anxious the 13-year-old felt about his future. Would he feel even worse if they lost again? Would people start to think of him as a bad kid?

That afternoon, talking with his dad about the letter, James quietly considered these questions. Then he went outside to watch the storm clouds.

Paige Pfleger of WPLN contributed reporting.