The Frist Art Museum’s latest exhibit opens Friday. It’s called “Art and Imagination in Spanish America.” The pieces you see are from 1500 to 1800, but what you hear in this exhibit are decedents of “Spanish America” in 2023.

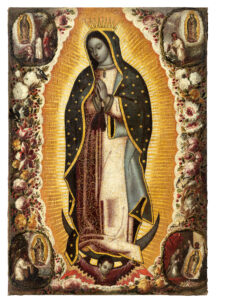

Walking into the gallery, I’m greeted by a familiar face: La Virgen de Guadalupe.

Courtesy Frist Art Museum

Courtesy Frist Art Museum Antonio and Manuel de Arellano’s “Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe)”

She’s all decked out, comparatively. I’m used to seeing her on a sun-bleached window sticker on the back of a classmate’s truck in high school. She was on the central bead of a friend’s wooden bracelet in college. A smaller portrait of her hung in the entryway to the only Catholic church in the small Latino community where I reported on agriculture labor issues after graduating.

This depiction of her is larger than life — nearly 7 feet tall and glowing in gold.

“In her gaze, a mosaic of compassion and grace reminds us that love is the utmost universal force,” says the audio track accompanying the piece.

The voice is of Carolina Gruber, an educator in Metro Nashville Public Schools and one of a dozen local Latinos the Frist asked to respond to these pieces.

“It is in the virgin’s tender eyes where the true enigma lies. For, within their depth, galaxies unfurl…”

There are QR codes scattered across the exhibit where you can scan to hear similar reactions to Carolina’s.

Meagan Rust is the Frist’s interpretation director who headed up this accompaniment project.

“For this show, the works created between 1500 and 1800 and a very specific context — Spain coming to the Americas, colonizing the region … we realized that the works could have a very different interpretation and response from our community today.”

I can see that in the mood change, as the tour group led by Ilona Katzew rounds the corner to a biombo — a folding screen, like the kind you’d change clothes behind.

Some in the group frown at how idyllic the scene of colonization is portrayed in the painting. Ilona, who is the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s curator and director of Latin American art, explains: “It depicts an indigenous wedding. You have the indigenous couple leaving the church on the right side and being greeted by a number of performances that hark back to ancient times but were performed in the Spanish colonial period as well.”

Courtesy Frist Art Museum

Courtesy Frist Art Museum Ilona Katzew, LACMA’s curator and director of Latin American art, explains to the tour group at the Frist what each piece of the screen is depicting.

There’s the Danza de Los Voladores — where men swing from a tall pole by a rope around one ankle. It takes a tremendous amount of strength and dexterity. And you see that — the awe almost — from those in the far left corner: the Spaniards.

“I do think that this is the kind of imagery that was sent back oftentimes to Europe to show how the two repúblicas — Repúblicas Hispañolas y República de Indios — were coexisting together. And, at the end of the day, it’s this kind of union that allowed the political entity that was New Spain to exist.”

It likely allowed me to exist, I realize.

This scene was painted in late 1600s Mexico, but across the gulf and Caribbean Sea, how different were my Taino ancestors’ interactions with the Spaniards at this time? As they renamed our island of Borikén — “Puerto Rico”?

Another Nashville Latino who answered Frist’s call for reactions is José Cárdenas Bunsen, a professor at Vanderbilt University.

“This screen captures the transformation and survival of indigenous cultures under colonial rule,” he said.

Rachel Iacovone WPLN News

Rachel Iacovone WPLN NewsIlona Katzew explains the series of “casta” paintings that depict the Spaniards’ belief of how to have whiter children by mixing with other races. They believed albinism was only genetic to those with African heritage.

It’s easy to walk through this exhibit a bit disheartened despite all the beautiful art. History is told by the victor, after all, or at least commissioned.

That comes up at the end though, when someone asks Ilona Katzew where the brutality of colonialism is addressed in art.

Her answer is, essentially, here — all around us — as she gestures to a nearby communion chalice.

When the Los Angeles museum took this piece made by indigenous artists apart and reassembled it, they discovered a silver plate hiding in the base — on it, was a conquistador’s severed head with a sword run through it.

“Art and Imagination in Spanish America” will be at the Frist through Jan. 28, 2024.

You can subscribe to our free, human-powered newsletter, the NashVillager, to get more stories like this in your inbox daily — here.