Even in his final months, John Jay Hooker had a cause.

He called it “death with dignity.”

“The day I start throwing up blood and am wracked with pain … I’m just in jail in that damn bed,” he said. “And I’m not a slave. The state of Tennessee doesn’t own me.”

“I’ve got the right to check out of that bed. Say good night.”

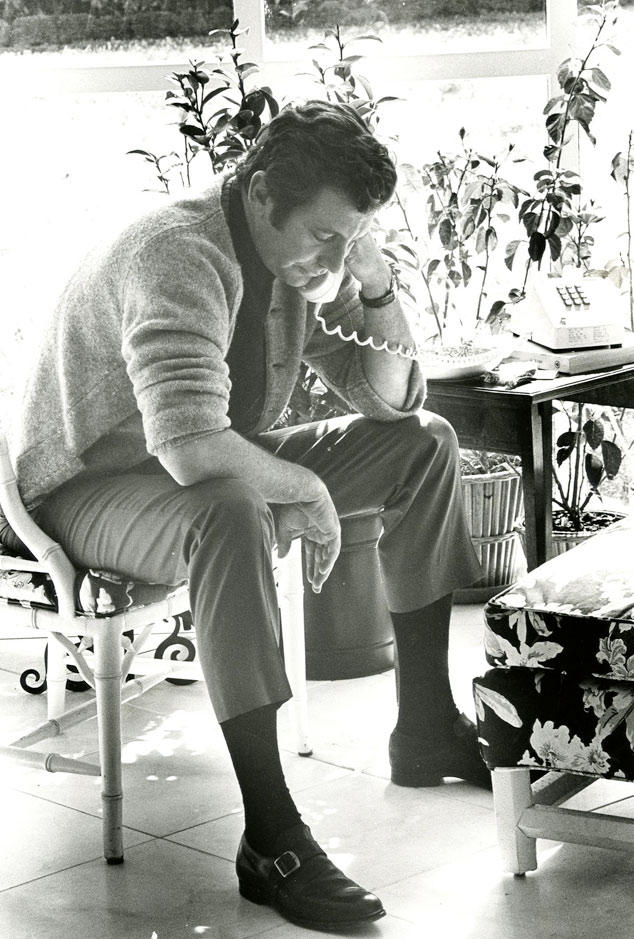

Hooker always knew how to make an argument. That was clear half a century ago, when he burst onto Tennessee’s political stage. Tall and dashingly dressed, with an Old South drawl and baritone delivery, Hooker looked and seemed like the state’s next great leader.

He would become a two-time Democratic nominee for governor. A businessman who made and lost a fortune. And a fighter for the right to vote and the right to die.

He has passed away.

Nashville lawyer Hal Hardin was there from the beginning.

“People flocked to see him,” Hardin recalled. “I mean, girls would scream at him and pull on his shirt. He could have the crowd in tears or laughter. Hollering, chanting. He was an amazing speaker.”

Hooker was an attorney by trade, but politics was in his blood.

He first decided to run for governor when he was just 8 years old, and he claimed the pedigree to do it. His father was one of Nashville’s most successful lawyers. An ancestor was William Blount, the territorial governor of Tennessee.

By his 20s, he was rising star in Democratic politics, working closely with the Kennedys — especially Bobby Kennedy. They met in 1958 when Hooker gave him a tour of the Hermitage.

“He missed his airplane going back, so he spent the night,” Hooker said. “And by the time we left, we were pals.”

For the next decade, Hooker remained at Bobby Kennedy’s side. Hooker urged him not to prosecute Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa, and Hooker worked with Kennedy as he and President John F. Kennedy dealt with the Cuban Missile Crisis. He was close to the family when the elder Kennedy brother was assassinated in Dallas in 1963, and he warned Bobby Kennedy to take precautions before he was fatally shot while campaigning for president in California five years later.

“I really truly loved Bobby,” said Hooker, “and I think Bobby loved me.”

By then, Hooker had made his own foray for public office. And in typical John Jay Hooker style, he went big.

With the Kennedys’ backing, Hooker made his first run for governor in 1966. He took on fellow Democrat Buford Ellington, a one-time segregationist.

The election was seen as a referendum on integration. Hooker was an ardent supporter of Martin Luther King. But he soon learned many white Tennesseans didn’t see eye-to-eye with him.

“I’d walk up and try to shake hands with them, and they’d spit — wouldn’t shake hands with me.”

Hooker lost decisively by more than 53,000 votes. But he ran again in 1970 against Republican Winfield Dunn.

That race would be one of the last to hinge on stump speeches and newspaper coverage. Nashville’s two major dailies, The Tennessean and The Banner, each picked a side. On the campaign trail, Hooker went toe-to-toe with his political enemy, Banner publisher Jimmy Stahlman.

“I’m going get up early in the morning and stay up late at night, and look in every eye I can find because one of these days I want James G. Stahlman to call me governor,” Hooker told one crowd of Nashville businessmen less than a month before the election.

The line drew wild applause. With lines like that, Hooker had audiences in the palm of his hand.

But the seeds of his undoing had already been planted. Two years before the election, Hooker had

launched a chain of fried chicken restaurants named after Grand Ole Opry star Minnie Pearl.

The idea took off, and Hooker quickly became one of Nashville’s richest men. But by Election Day in 1970, federal investigators were looking into the company’s bookkeeping. Hooker blamed that old Kennedy nemesis, President Richard Nixon.

“He sicced the Securities and Exchange (Commission) on my business,” he said. “And you talk about the enemies list. … They just destroyed this business. It was a great business.”

Hooker was defeated a second time. The loss would be more costly than the first. Not only had he failed to secure the governor’s office, his reputation was in tatters.

For the rest of his life, Hooker would claim losing in 1970 kept him from becoming President of the United States. He said it would have been him — and not a Georgia governor named Jimmy Carter — who would have captured the Democratic nomination in 1976 and vaulted into the White House.

Hardin, his former campaign aide, says that’s not far-fetched.

“I mean, the national correspondents were down here. They just didn’t come to any state,” he said. “I think they were looking for another, Jack Kennedy-type individual. And it really wasn’t hyperbole. There were a lot of people who felt that way.”

Still, Hooker didn’t give up. He ran for governor three more times. For the Senate, twice. For the U.S. House of Representatives and for judge.

Each time he lost.

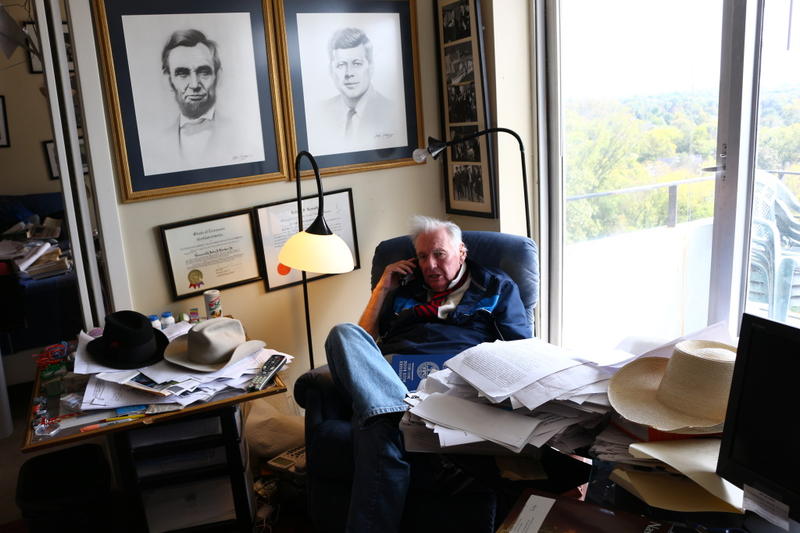

But by the end, his focus was less on winning office than in advancing his pet causes — campaign finance reform and overturning the state’s system of choosing judges.

“They tried to act like they thought I was crazy. They called me a gadfly, anything they could to besmirch me,” he said. “The one problem was, they knew the hell that I was right.”

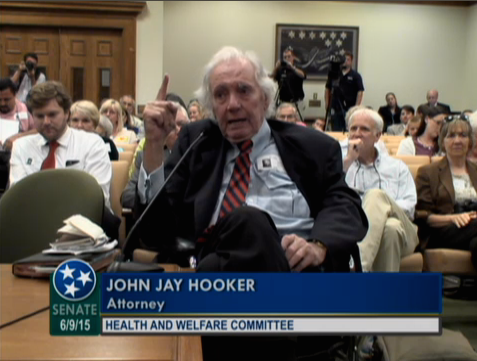

Hooker wanted judges to be elected directly. Quoting the Tennessee Constitution, he said the state’s founders had meant for the judiciary to be picked by the voters.

But he lost that campaign too, when Tennesseans approved a constitutional amendment in the fall of 2015 to let the governor pick justices, with voters having the option of reaffirming their appointments through retention elections.

Soon afterward, Hooker would begin telling friends that he’d been diagnosed with cancer — and that he had about six more months to live. He responded with a final crusade: to legalize doctor-assisted suicide in Tennessee.

The effort didn’t seem to tire him. Instead, it appeared to give him strength.

“I just feel grateful for the opportunity to be in the fight,” Hooker said in an interview shortly before his death. “Instead of sitting around here, thinking about tomorrow, I’m thinking about the fight today.”

For his final campaign, Hooker asked Hardin, that former aide, to be his lawyer. Hardin accepted. It was a way to repay his mentor for some advice given nearly 50 years ago.

At the time, Hardin had just returned from the Peace Corps. He’d been sent to South America, where he’d been given responsibility over a village full of people.

“I said, ‘I’ll never — I’m just in my 20s now — I’ll never have another experience like that in my life. It’s impossible,'” Hardin remembered. “And he got very calm and he looked over and he said, ‘Let me just tell you something, young man. Don’t ever let that be your high noon.’

Hardin chuckled as he imitated Hooker’s low, rumbling drawl.

“I remember that. Don’t ever let that be your high noon. You try other things.”

Even as he approached life’s sunset, Hooker refused to let any moment be his high noon.