When Tanja Jacobs couldn’t get in touch with her 22-year-old son on Memorial Day, she started to worry. But she was more than a thousand miles away in Colorado.

So early that morning, she asked her ex-husband to check on their son at his apartment in Nashville. And they were on the phone together when he opened the door.

“And, the next thing I know, he screamed and he cried like I’ve never heard anybody cry,” she says.

Jacobs says her ex-husband found their son on the couch, at first thinking that he was asleep.

“He had been gone,” she says. “And I heard all that in the background, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God.’ ”

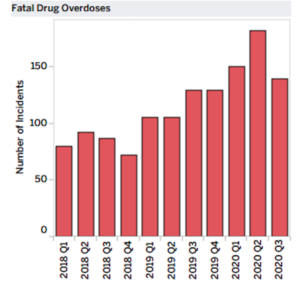

Jacobs’ son was one of the nearly 500 people who have died from a drug overdose this year in Nashville. Across Davidson County, the number of drug-related deaths since January has already surpassed last year’s record-setting toll.

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department An uptick in fatal overdoses in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a deadly trend that was already on the rise.

Overdoses have spiked during the pandemic, both here and across the country. And fentanyl has caused the vast majority of deaths.

“For the past couple of years, we have moved from around 60-something percent of deaths involving fentanyl. We are now around 80% this year,” says Trevor Henderson, director of the Metro Public Health Department’s opioid overdose response and reduction program. Henderson says many people who were once dependent on prescription pills are now turning to illicit drugs laced with fentanyl — often unknowingly.

“That’s becoming the big driver of both fatal and nonfatal overdoses,” he says. “So, things have become a lot more volatile.”

Then COVID-19 hit and cut people off from their support systems, while public health officials shifted into crisis mode.

A double public health crisis

Henderson says more research is needed to draw any conclusions. But he thinks social isolation and stress from the pandemic seem to have played a role in the uptick in deaths.

“Last year, things were bad and getting worse,” he says. “Once we hit around March of this year and we started having to get into COVID response and lockdowns and things like that, we did certainly notice that the overdoses were amplified.”

Henderson says public health officials can’t just focus on the pandemic while an overdose crisis is playing out in the background. His department is hoping to partner with churches, first responders and anyone else who can help to connect people with the resources they need.

Even though Jacobs lives on the other side of the country now, she has volunteered to play a leading role in those outreach efforts from afar. She’s also started a support group for those who have lost their loved ones, called Nashville Families Fighting Against Fentanyl Overdose.

Jacobs has partnered with veteran activists Clemmie Greenlee and Sheila Clemmons Lee, who have both spent years supporting mothers who have lost their children to gun violence. Clemmons Lee’s son, Jocques Clemmons, was killed by a Nashville police officer in 2017.

Jacobs hopes their experience in community organizing will help her reach more people in need — maybe even those who don’t yet realize their loved one is struggling.

Courtesy Tanja

Courtesy Tanja Jacobs commemorates her son, who died of an overdose in May, with a shrine in her living room.

“I wonder how many people don’t know about it and are not aware of it,” she says. “That’s why we’re trying to come up with a way to, you know, get the word out about this to save other people from having to go through the same heartache that we went through.”

When Jacobs misses her son, she admires a shrine in her living room she created in his honor, filled with poems and photos and an urn with his ashes.

“I know he loved me. And I hope he knows how much I loved him,” she says, swallowing back tears. “But, I think he would have made a good life for himself.”

Jacobs wishes she could have saved him. Could have seen the warning signs.

But she hopes that, with her help, other will before they lose their loved ones.

If you or someone you know is struggling with addiction, you can reach the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration help line at 1-800-662-4357 or Tennessee REDLINE at 1-800-889-9789.

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.