Hospitals in much of the country are filling up with COVID-19 cases, approaching 84,000 patients at the start of this week. But space isn’t the main concern. It’s staffing. And bringing in backups from out of town isn’t the solution it was early in the pandemic, when the surge was concentrated in a handful of cities.

Finding reinforcements really wasn’t a problem with the first wave of COVID-19 back in the spring. Hospitals in most of the country were seeing fewer patients than normal, resulting in mass layoffs, so nurses were excited to catch a flight and join the effort.

“It was really a hot zone, and we were always in full PPE and everyone who was admitted was COVID positive,” says Laura Williams of Knoxville, who helped launch the Ryan Larkin Field Hospital in New York City.

“I was working six or seven days a week, but I felt very invigorated.”

After two taxing months, Williams returned to her nursing job at the University of Tennessee Medical Center. The COVID front had been relatively quiet — until now, with record hospitalizations in Tennessee nearly every day, increasing by 60% in the last month.

And backup is getting much harder to find.

Tennessee built its own overflow field hospitals — one in the old Commercial Appeal newspaper offices in Memphis and another on two unused floors of Nashville General Hospital. But right now, the state would have trouble finding the doctors and nurses to run them because hospitals are struggling to staff the beds they have.

“Hospital capacity is almost exclusively about staffing,” says Dr. Lisa Piercey, who heads the Tennessee Department of Health. “Physical space, physical beds, not the issue.”

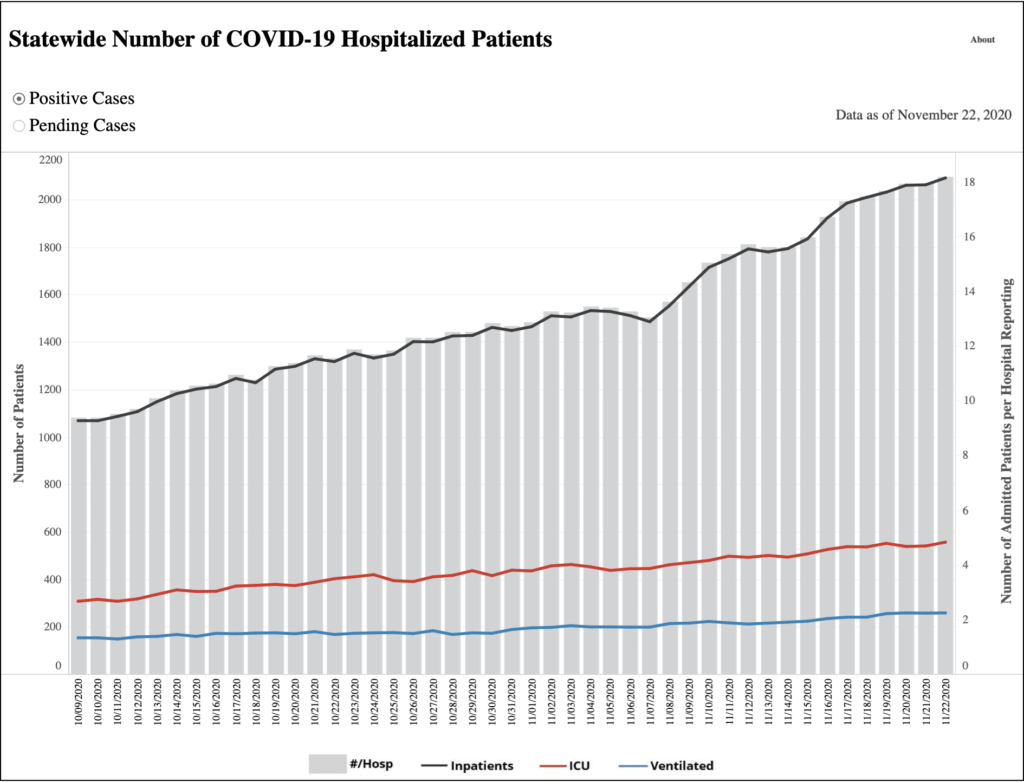

Courtesy TDH

Courtesy TDH Hospitalizations in Tennessee have been rising steadily for weeks.

COVID creates a compounding challenge for staffing.

As cases rise to new highs, record numbers of hospital employees are out themselves with COVID-19 or because they have to quarantine.

“But here’s the kicker,” says Dr. Alex Jahangir, who chairs Nashville’s coronavirus task force. “They’re not getting infected in the hospitals. In fact, hospitals for the most part are fairly safe. They’re getting infected in the community.”

Some states, like North Dakota, are already allowing COVID-positive nurses to keep working as long as they feel OK, though they’ve faced a bit of a backlash. Colorado, California and Illinois have asked retired nurses and doctors to consider returning to the workforce.

In Tennessee, Gov. Bill Lee has granted an emergency order dropping some restrictions on who can do what within a hospital, giving them more staffing flexibility.

For months, staffing in much of the county had been a concern behind the scenes. But it’s becoming palpable to any patient.

Dr. Jessica Rosen is an emergency physician at Saint Thomas Health in Nashville, where diverting patients has been rare over the last decade. Now she says it’s a common occurrence.

“We have been frequently on diversion, meaning we don’t take transfers from other hospitals,” she says. “We try to send ambulances to other hospitals because we have no beds available.”

Even the region’s largest hospitals are filling up. This week, Vanderbilt University Medical Center made space in its children’s hospital for non-COVID patients. Its adult hospital has more than 700 beds. And like many hospitals, it’s had the challenge of staffing two intensive care units — one for COVID patients and another for everyone else.

Arriving from hundreds of miles away

“The vast majority of our patients now in the intensive care unit are not coming in through our emergency department,” says Dr. Matthew Semler, a pulmonary specialist at VUMC who works with COVID patients.

“They’re being sent hours to be at our hospital because all of the hospitals between here and where they present to the emergency department are on diversion.”

Semler says his hospital is taking patients from as far away as Arkansas and southwest Virginia. It would typically bring in nurses from out of town to help, but there is nowhere to pull them from right now.

National systems are still moving personnel around, though increasingly it means leaving somewhere else a little short-staffed. In Texas, Dr. James Johnson with the physician services firm Envision has deployed reinforcements to Lubbock and El Paso this month.

Courtesy Dr. James Johnson

Courtesy Dr. James Johnson Dr. James Johnson is an anesthesiologist and worked four weeks in New York City early in the pandemic.

He says the country hasn’t hit it yet, but there is a breaking point.

“I honestly don’t know where that limit is,” he says.

And the limitation at this point won’t be ventilators or protective gear. In most cases, it will be people.

So Johnson, who is an Air Force veteran who treated wounded soldiers in Afghanistan, says he’s more focused than ever on trying to boost morale and stave off burnout.

He’s generally optimistic, especially after serving four weeks in New York City early in the pandemic.

“What we experienced in New York and happened in every episode since is that humanity rises to the occasion,” he says.

But it shouldn’t just be sacrifices for health care workers. Johnson says everyone bears a responsibility to keep themselves and others from getting sick in the first place.