The murder case against a Nashville police officer entered the criminal court on Wednesday, and already a legal battle has sprung up between prosecutors and the defense.

At issue is whether a large amount of records — such as police reports, interviews, forensic tests or other materials — will be publicly available before the trial against Officer Andrew Delke. The officer has been indicted on a charge of first-degree murder in the July shooting death of Daniel Hambrick.

Defense attorney David Raybin filed a motion this month asking a judge to either seal the records in the court clerk’s office, or to order prosecutors to give the materials directly to the defense, outside of the courthouse.

Raybin is specifically asking for a change to how “discovery” materials are handled. These are the records and pieces of evidence that criminal defendants are entitled to receive from prosecutors as they prepare their defense for trial.

“The advanced disclosure of evidence can easily become part of the public domain, and work to the prejudice of the defense and the state,” Raybin writes. (

View full motion as PDF.)

But in a response filed Wednesday, District Attorney Glenn Funk rebuts the defense’s suggestion, asking the judge to come down on the side of “transparency.” (

View the full response as PDF.)

“To ensure the citizens of Davidson County are confident that the judicial process is fair and that all persons are treated equally,” Funk writes.

Common Courtroom Practice Debated

Raybin argues discovery materials can include information that would later be deemed inadmissible at trial, and that witnesses could encounter the records and then, “magically ‘remember’ things based on what they have seen on the television.”

Raybin acknowledges Nashville courts have made these documents publicly available for years, part of the routine lead-up to a trial, but argues the public disclosure is not required by law.

“Nothing has changed in 30 years. It is time that it did,” he writes.

Funk, the prosecutor, argues that all parts of the high-profile case should be open, and notes that discovery is publicly available, “in almost every case in Nashville.”

Discovery materials are often reviewed by journalists, shedding light on how authorities carry out investigations and what types of evidence will be involved at a trial.

In recent years, records in some criminal cases have been sealed by judges’ orders. Raybin has been the lawyer making that request before.

Conflict Of Interest Suggested

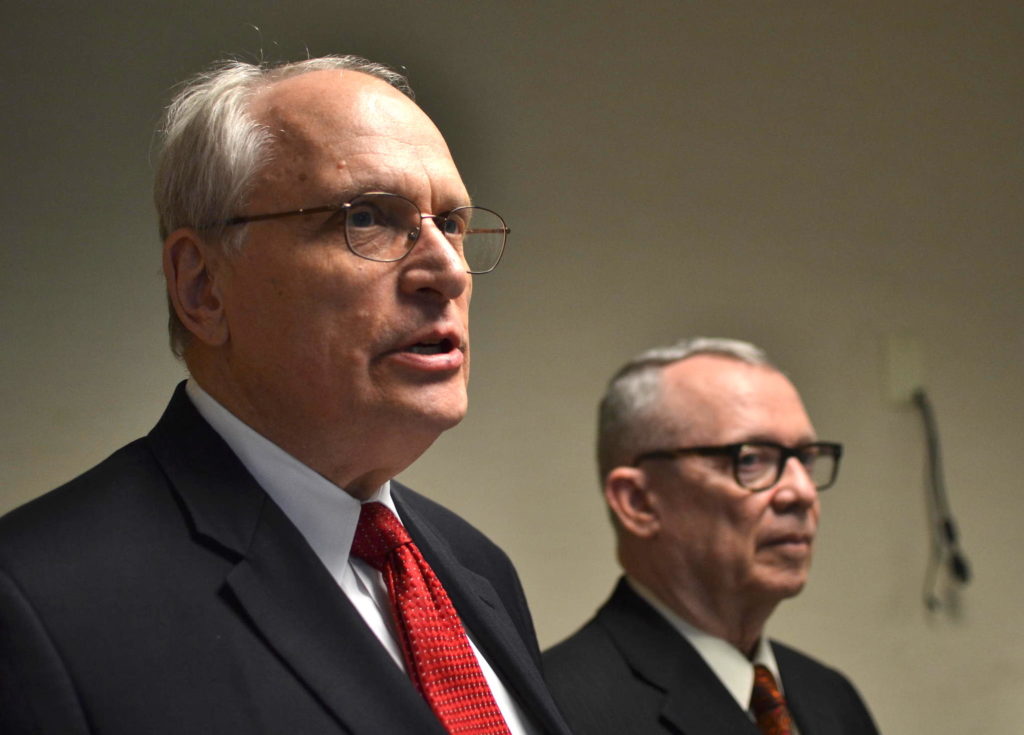

Also new, Funk is raising a concern about a possible conflict of interest with the defense team of Raybin and John M.L. Brown.

Funk notes that the pair represent Delke as well as the local Fraternal Order of Police, which recently announced a public campaign to support Delke.

“The State submits the ‘campaign’ contains misinformation, mistruths and untruths that will be shown as such by having an open, transparent exchange of discovery materials,” Funk writes.

He goes on to request that the judge directly ask Delke whether he is aware of the potential conflict, and what his position is about his representation.

Similarly, Funk notes that some witnesses who may be called to testify against Delke have been represented by the same attorney, Brown, who is defending Delke. The prosecutor doesn’t say what the judge should do, other than take “action as it deems necessary and appropriate.”

The attorneys are expected to argue over the discovery records at a hearing next Tuesday.