Nearly fifty years ago, Bob Dylan gave Nashville his stamp of approval, and an astounding number of pop, rock and folk musicians took notice. For more than a decade, they flocked here to cut song after song. But a look at the credits of those songs hints at a deeper tale about how the city’s session players used that influx of star power to expand their own careers — and Music Row.

This is the story of Music Row’s second generation, a loose collection of instrumentalists nicknamed the Nashville Cats. They were the guys the Lovin’ Spoonful sang about:

Nashville cats play clean as country water

Nashville cats play wild as mountain dewNashville cats been playin’ since they’s babies

Nashville cats get work before they’re two

The Cats were baby boomers who honed their chops playing rock and roll and rhythm and blues. They knew there was good pay and steady work backing up singers in Nashville recording sessions, so they migrated to Music Row.

Then they learned to work the Nashville way: instead of relying on written arrangements or taking hours to feel out a song, musicians were expected to improvise the right thing just minutes after hearing a producer play an example of the rhythm and the chord changes.

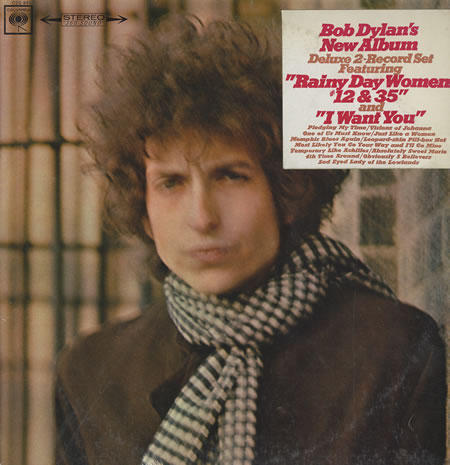

Enter Bob Dylan

Dylan had just spent four months in a New York studio — working on the follow up to his hugely successful Highway 61 Revisited — and had just one finished track to show for his time. But in early 1966, with the Cats at his side, it took Dylan just a handful of sessions in a Nashville studio to cut a double album many consider his masterpiece: Blonde on Blonde.

Dylan returned for his next two albums, even naming one Nashville Skyline. And in a move unusual for the time, Dylan made a point of clearly crediting each musician on the album sleeve.

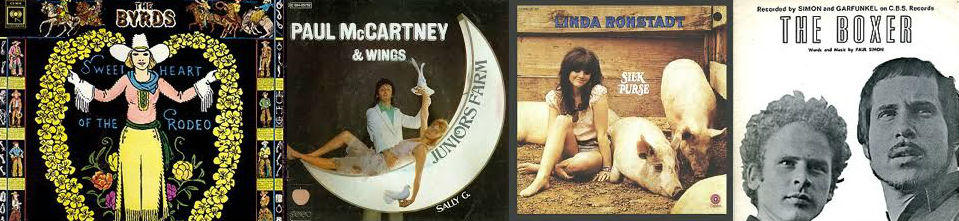

Word quickly spread about what the talented players here could do beyond the bounds of country.

The recipe became this: put together one musician with folk influences with another who really knows R&B, maybe throw in a great fiddle player, and bank on the idea that they all have the ability to improvise arrangements.

The results were records that are “indefinable” and “still fresh,” says Pete Finney, the musician who co-curated the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s

Dylan, Cash and the Nashville Cats exhibit. What’s more, Finney says those visiting stars gave the Cats a sense of possibilities for their own projects.

Careers Launched, Studios Built

Charlie Daniels launched his solo career after working those sessions. Mac Gayden wrote the R&B hit “Everlasting Love.” About a dozen of the Nashville Cats formed a band called Area Code 615; when it broke up, several formed another group, Barefoot Jerry. Guitarist Wayne Moss, who was in both bands, had built one of the city’s first home studios in his garage, called Cinderella Sound. Area Code 615 cut tracks there even while its members maintained an unrelenting pace of three or four three-hour sessions each day.

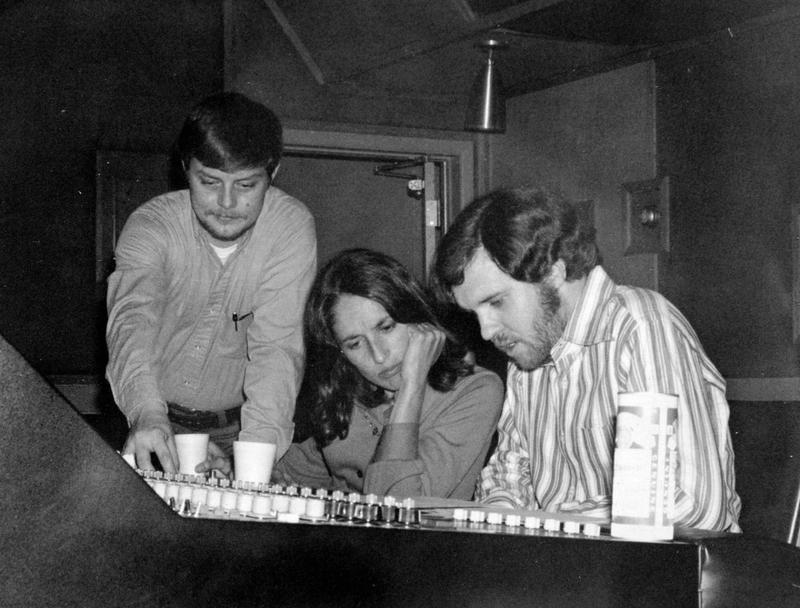

In 1969 alone, Norbert Putnam says he did 625 “record dates.” He was 28 years old, exhausted with an aching back and hands calloused by the bass strings. He needed to slow down. Putnam bought an old house on Music Row with another Cat, pianist David Briggs. The pair intended to open publishing business. But Nashville really needed more places to record.

They ended up creating the now-legendary Quadrophonic Studio instead. Drum kits went in the kitchen, singers in the living room (complete with fireplace in the corner). The front porch was enclosed to become the control room. It was equal parts homelike and high tech, with a near-total lack of reverberation in the small rooms that gave recordings a tight sound Putnam describes as “hifi.”

It’s the sound you hear on Joan Baez’s

top five hit “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” produced by Putnam, and the Dobie

Gray classic “Drift Away,” produced by Briggs. Neil Young’s classic album Harvest was recorded there.

A handful of small studios started to spring up around town, each with a looser, less corporate approach to recording than what Music Row had known before. In them, the Nashville Cats weren’t just playing instruments – beyond Putnam, Moss and Briggs, folks like drummer Kenny Buttery and pedal steel player Ben Keith were taking on tasks like producing and engineering. They were also shifting the balance of what business was done on Music Row by working with artists who wrote their own music.

That didn’t always sit well. Country music at that time made its biggest profits from publishing, not record sales. The boom in recording work didn’t shuttle money into the city’s publishing companies if the musicians didn’t need to buy songs. Putnam jokes that once he started producing million sellers, he didn’t get invited to many parties anymore.

But publishing houses adjusted. Singer-songwriters became an integral part of Music Row’s fabric. In the end, folks like Norbert Putnam didn’t need to change to fit in with the Nashville establishment; instead, the city’s music business evolved to be more like the Nashville Cats.