Winter determines which plants can grow and thrive in cities.

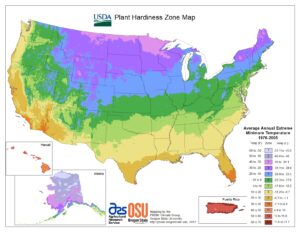

Specifically, the lowest winter temperature is how researchers divide plants into growing regions, called plant hardiness zones.

“A plant hardiness zone is really just defined by the coldest night of the year,” said John Abatzoglou, a climatology professor at the University of California, Merced.

Zones are calculated by the annual minimum temperature, averaged over 30-year periods. There are 13 zones, separated by 10 degrees Fahrenheit, and each zone is further divided into five-degree subsets called a and b.

Zones are calculated by the annual minimum temperature, averaged over 30-year periods. There are 13 zones, separated by 10 degrees Fahrenheit, and each zone is further divided into five-degree subsets called a and b.

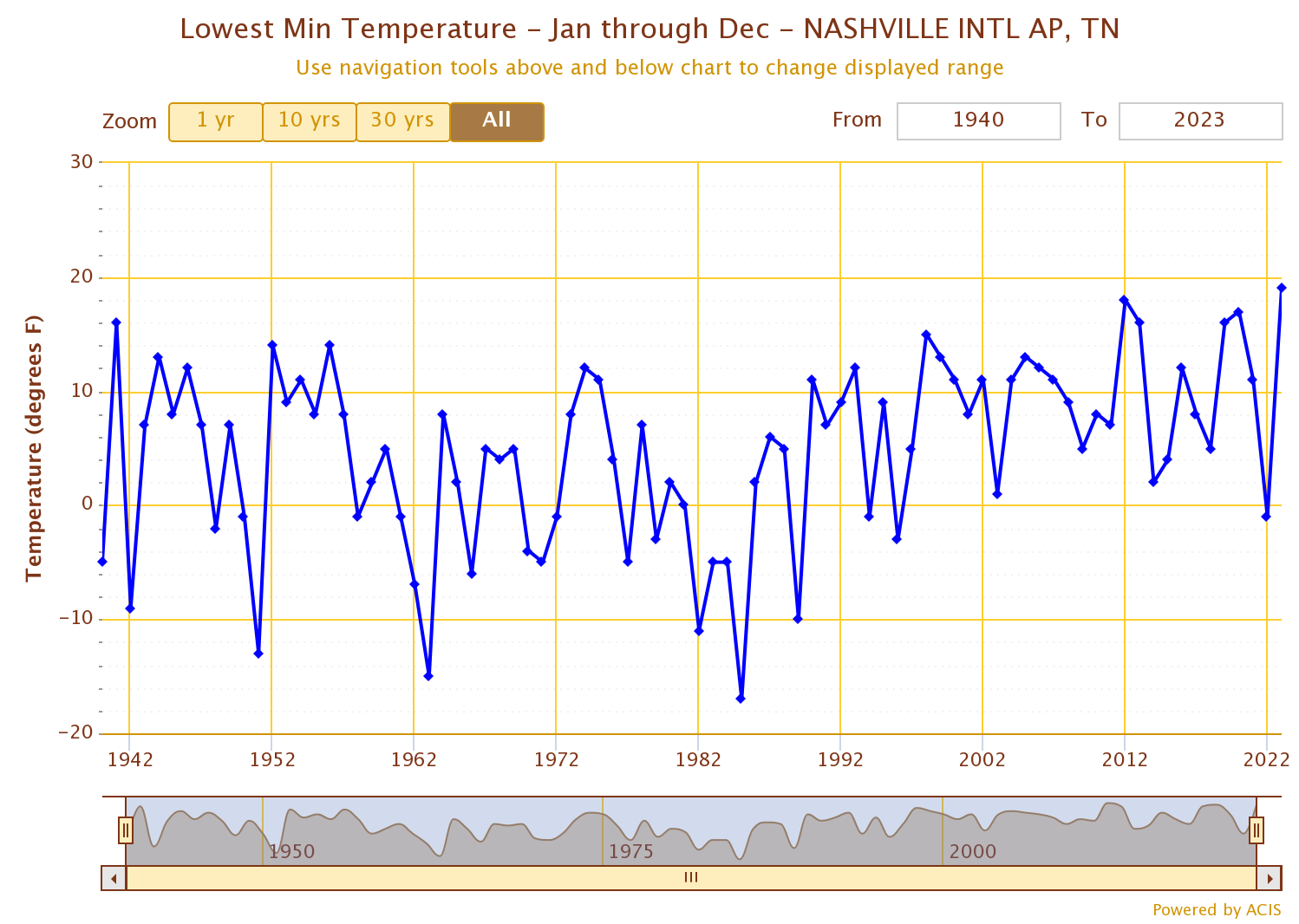

As the cooler periods have warmed, zones have been shifting north over the last three 30-year periods. That trend will continue with further climate change, and it is already evident in Nashville.

Nashville may shift to Zone 8

Nashville is currently listed as Zone 7a, based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2012 plant hardiness zone map. That zone is defined by an average low of 0 to 5 degrees, and it supports edible species like blueberries and pecan, walnut and apple trees.

Since 1950, the city has recorded a significant jump between the lowest and highest average annual minimum temperatures, from -0.3 to 9.2 degrees. That represents the third-highest difference in the nation and a jump from Zone 6 to 7, according to new analysis by Climate Central.

Courtesy Climate Central

Courtesy Climate Central Nashville’s average minimum temperature is getting warmer.

Nashville may now be part of Zone 7b and could move into Zone 8 by 2040 with additional warming.

Warmer lows can bring positive and negative outcomes to the region, according to Abatzoglou.

“You may end up having the potential to have species that would have otherwise perished,” he said.

For agriculture, this can be profitable. Abatzoglou’s research has shown expanded ranges for high-value crops like almonds and kiwis.

Botanical gardens are making adjustments

Nashville’s shifting planting zone has also affected local botanical gardens like the Cheekwood Estate and Gardens. Gardeners have been experimenting with cultivating new displays because of local warming, according to Peter Grimaldi, Cheekwood’s vice president of gardens.

“You can make selections and grow and display things successfully that may be more native to parts of the southern and southwestern United States or warmer climates all over the world,” Grimaldi said.

Cheekwood introduced more yucca, agave and Southwest-native succulents to its literary garden this spring, Grimaldi said.

But there is a flip side. Cheekwood gardeners cannot get away with planting “dripping, silvery-blue confiners, overflowing ferns or Norway spruces,” Grimaldi said.

The warmer climate may also impact which pests and weeds can thrive in the area.

Nashville winters are getting warmer

Nashville has dipped below zero just three times in the past three decades, departing from the previous 50 years.

Despite a memorably-freezing Arctic blast this past December, Nashville winters and wintertime lows have been getting warmer. The city has dipped below zero just three times since 1990, a departure from the previous five decades.

Grimaldi is concerned with how warming can also deliver more Arctic blasts, since it only takes one freeze to wipe out flowers.

“The extreme highs and the extreme lows are going to really start pushing and pulling things in and out of what you can and cannot grow,” Grimaldi said.