There was a day when Curious Nashville listener Kymberly Horth voted at Belle Meade City Hall and then drove through Berry Hill. It made her wonder about those places, and how they relate to Davidson County:

Why do Berry Hill and Belle Meade have their own police departments? Are there any other special services these neighborhoods have?

The answer has ties to the creation of consolidated Metro government nearly 60 years ago.

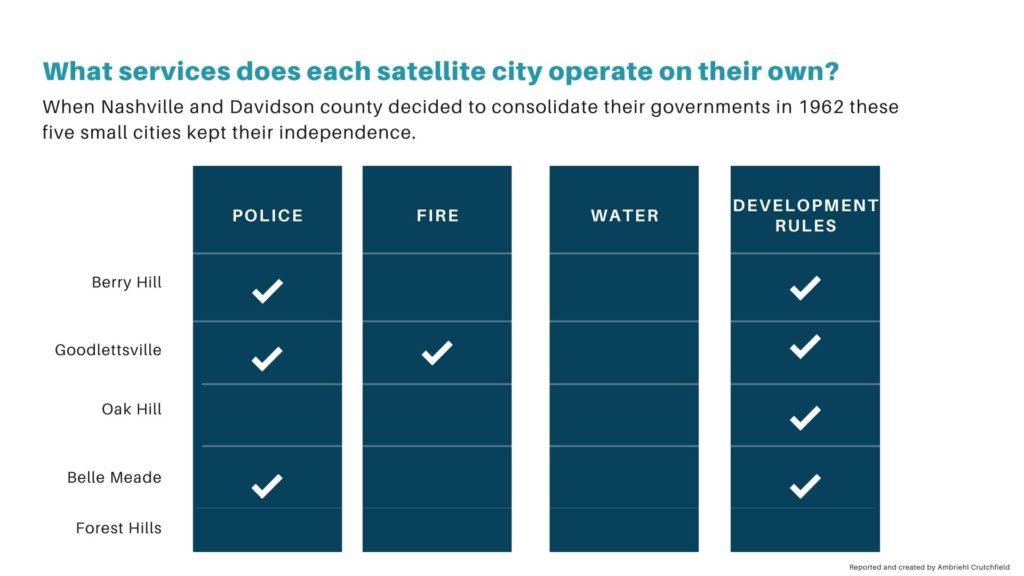

Berry Hill, Belle Meade, Oak Hill, Goodlettsville and Forest Hills are known as Davidson County’s satellite cities.

They feel like they’re a part of Nashville but have their own governments. They provide some of their own city services — like trash pick-up — but rely on Metro for others, like the fire department.

To understand why they were created, we have to dig into how Davidson County and Nashville became one government.

Lurching toward consolidation

It’s just after World War II and some people in Nashville want to spend their recently earned money on new houses and amenities.

Middle class Black people start heading for the suburbs, especially north of Tennessee State and Fisk universities. White families are also moving outside the city limits.

Nashville’s small core is deteriorating.

“And the county’s growing and the city is not,” says Davidson County Historian Carole Bucy. “That is the single problem. How do you balance the tax base and keep the city vibrant?”

A key problem is both governments aren’t operating efficiently, often duplicating services.

The health director of the time, Dr. John J. Lentz, brings this issue to the forefront and helps sway then-Mayor Ben West to understand how consolidation would benefit the city.

So, with the city core struggling, Bucy says professors from Vanderbilt University and the University of Tennessee come together to create a 150-page report called “Future for Nashville.”

Charter commission picks up steam

West and County Judge Beverly Briley — who later would become the first mayor of the consolidated government — created a commission to work out a charter and to gain voter support. City and county voters would both have to be convinced to approve consolidation.

Meanwhile, the school system had introduced its integration plan, accelerating the number of white people leaving the city.

But some areas — the future satellite cities — generally opposed the idea of higher taxes or integration. So, areas like Berry Hill and Oak Hill formed their own governments.

Others in the county were opposed because it would increase their taxes.

On the first vote, in 1958, consolidation failed.

Mayor changes strategy

“Alright, Ben West is mayor of a city that has trouble, financial trouble,” Bucy says. “So, what does he do? He and the city council they annex a couple … different parts of Davidson County.”

By choosing annexation, West tripled the size of Nashville and added parts of the county that had large businesses, like the Ford Glass Plant and Aladdin Industries.

Taxes went up in annexed areas without the city offering more services.

And it increased the city’s white population while weakening the political clout of African Americans.

“He scared the hell out of them,” former Tennessean publisher John Seigenthaler said in an oral history. “On that day, Metropolitan government became a reality. That act brought about the change.”

Areas that had not been annexed became fearful of West, saying, “he’s not going to come and get us.”

West also implemented a green sticker tax for county people coming to work in the city. In the long run, this damaged his legacy.

Nashville Public Library

Nashville Public Library A photograph of Charter Commission members at work, circa 1962. Pictured here, from left to right, are Alexander Looby, Cecil Branstetter, Harlan Dodson, and Edward Hicks. These four men were appointed to both the first and second Charter Commissions.

At the same time, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were in the Cold War. So some began to use messaging that painted consolidation as a step toward a local communist government.

That left Black residents split on consolidation. Churches would host debates to discuss the pros and cons.

Prominent Civil Rights lawyer and Councilmember Z. Alexander Looby served on the first charter commission. He became a symbol in Black communities as being liberal and willing to make changes because of his pro-consolidation stance.

On the opposing side was Black firefighter and Councilmember Bob Lillard. The disagreement was intense enough that some portrayed Lillard as an ‘Uncle Tom,’ because they saw his stance as old-fashioned.

Black Nashville native Mansfield Douglas would go on to become a councilmember after consolidation. But in an oral history, even he wasn’t fully on board.

“Quite frankly, I never really did have a lot of enthusiasm for consolidate the government because it would diminish the percentage of the minority population,” he says.

In the end, a good number of African Americans got behind consolidation, in part out of the belief that it would benefit education in the long run.

Douglas says he also remembers people also supporting consolidation as a way of getting back at West. After annexation, he had flipped to oppose the second consolidation attempt. And he had closed the city’s pools when Black leaders tried to integrate them.

“Simply because the swimming pools had closed out of fear for confrontation,” Douglas says. “That allowed them to feel at ease in support of consolidation. They felt like Ben West was opposed to it.”

A second attempt

The revised charter proposal included more representation of African Americans, as well as the addition of at-large councilmembers who would represent the entire county.

The Metro merger also distinguishes between an interior urban services district — which is taxed at a higher rate and gets more government services — and the outlying general services district.

These tweaks, and changing attitudes, led enough county and city voters to support consolidation.

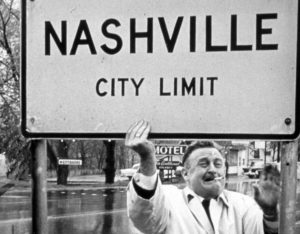

Metro Government Archives

Metro Government Archives A photograph of former Mayor Beverly Briley removing Nashville city limit sign, circa 1962. Many city limit signs were initially removed due to the city’s annexation of large portions of Davidson County. The remaining signs were removed following the consolidation of the city and county governments.

Metro was born in 1962. And the government was implemented the following spring.

Decades later, some officials are still celebrating. There were 50-year anniversary festivities, including a ceremonial birthday cake in 2013. And Metro became a model for other local governments.

Some credit the consolidation for landing multiple professional sports teams, improving education and the police department and expanded liquor sales in the county.

It also allowed those few satellite cities to avoid annexation and govern their own way.

But historian Bucy says she isn’t sure county or city voters would support consolidation again — especially not African Americans.

“It did create efficiency in government. Look at our magnificent park system, our public library system,” she says. “It is really remarkable that we have have developed as a a vibrant city. But I don’t think it would happen today. And, yes, African Americans have borne the burden of of pretty much a lot of decisions that were not necessarily in their interest.”

For example, Bucy says African Americans had some seats at the table for big city decisions that followed consolidation — like the placement of interstates and the sweeping changes of urban renewal — but not enough power to stop the bulldozing of their communities.

Correction: This story originally included an inaccurate year. The 50-year anniversary commemoration of Metro took place across 2012 and 2013, with a ceremonial cake cutting in 2013, not 2012. The events celebrated the public’s vote in 1962 and the formation of Metro in 1963.