We’ve asked you for your questions about the pending vote on Nashville’s mass transit plan. Now, we’re trying to answer them.

What follows below is a Q&A format, numbered for convenient reference. Early voting runs from April 11 to 26, with the vote culminating on May 1. (You can continue asking questions

here.)

Several of your transit questions have been, or will be, addressed in WPLN’s ongoing coverage (

wpln.org/transit). Recent explanatory stories include:

- Nashville’s 55-Page Transit Plan Explained In 800 Words

- Why Nashville’s Transit Plan Relies On A (Contentious) Sales Tax Increase

- What Would Change First If Nashville’s Transit Referendum Passes?

Our Most Frequent Questions

One question has come in more than any other:

1. Is the transit plan “set it in stone,” or can it be modified as needed? Will there be any option to adapt the plans over the next 15 years?

The answer is: Yes, there is some flexibility in

the 55-page plan, with many specific details that would need to be hammered out in the coming years.

However, there are elements of the plan that cannot easily be altered. Because Metro is asking for tax increases to pay for this transit plan, officials had to put a plan in writing. Metro cannot dramatically change that proposal without getting permission (again) from the voters.

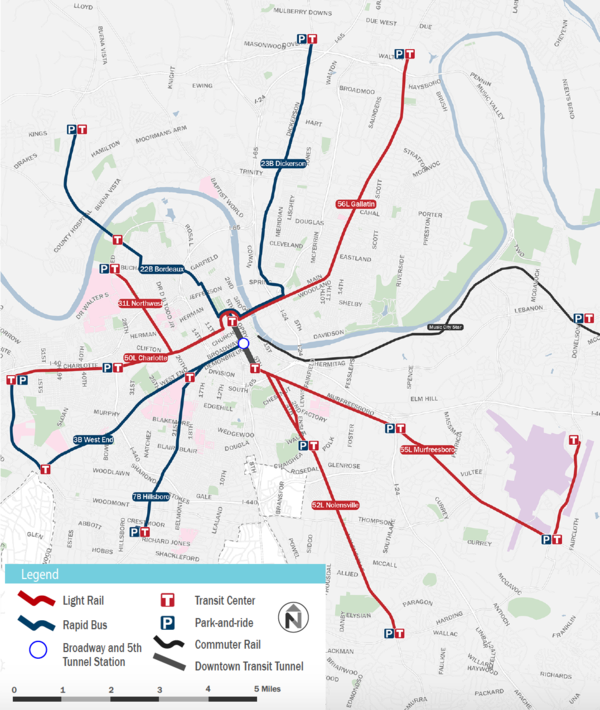

Let’s begin with what is most set in stone: If the referendum passes, Nashville would be committing to the nine high-capacity transit corridors that are spelled out in the 55-page plan (five light rail lines and four rapid bus lines).

Metro would not be able to eliminate one of those major routes, or add a different one, without first holding

another referendum. This is according to a Metro Law Department memo that analyzes state law:

If any project that is part of the Transit Improvement Program becomes unfeasible, impossible, or not financially viable, then the revenue can be directed to other transit projects upon the approval of the Metropolitan Council and the voters.

Another element that could not change is the financing method.

Metro is asking voters to raise four types of taxes and plans to issue bonds and seek federal funds — and to use that money exclusively on this transit plan. Metro would not be able to raise a different tax later without another referendum, nor could they take some of this transit tax money and spend it on something else. (This is also what officials mean when they talk about “dedicated funding for transit.”)

Flexibility enters the picture with the innumerable specific details of actually constructing such an ambitious transit system — such as where the bus and train stops would be located, where the 19 new transit stations would be built, where the new sidewalks would be poured, how the new bridges would be designed and so on. There could also be technological changes, including the precise type of light rail that would be built.

Engineers, environmental studies, community input and reviews by the Tennessee Department of Transportation would all factor into the block-by-block functioning of the system.

2.

Will there be opportunities to provide input on the details of the plan if it passes in May?

Yes.

None of the exact locations of the bus or rail stops have been determined, so residents could advocate for (or against) particular locations. MTA Executive Director Steve Bland said he would anticipate dozens of community meetings related to the specifics of each transit corridor.

“You literally have to go block to block along a corridor like Gallatin Road to assess how you’re going to deal with certain design constraints, how you’ll deal with construction impacts, how you’ll deal with the employment opportunities and residential opportunities,” Bland said. “Public input will be a key cornerstone of what we do.”

3. What specific bus and bicycle/pedestrian improvements can we expect? If they are not identified, how will they be if the referendum passes?

The specific bicycle and pedestrian improvements are not spelled out in the 55-page plan — but the plan is an outgrowth of both the

nMotion plan and the Metro Public Works

Walk ‘n’ Bike plan, so the priorities in those documents would guide the streetscape.

While not granular down to the block level, the proposal going to voters does call for funding the addition of sidewalks along all nine high-capacity lines and likely into the surrounding neighborhoods in those areas.

Detailing The Light Rail Lines

Light rail. It has been grabbing the headlines (and stirring up questions) since the MTA first included the possibility of light rail in its planning in 2016. Creating five light rail lines — along Gallatin, Charlotte, Murfreesboro and Nolensville Pikes, as well as one through North Nashville — would account for 61 percent of the plan’s spending.

4. Are they going to widen the roads getting light rail?

Yes, there would likely be some light rail corridors that need road widening, according to Erin Hafkenschiel, director of transportation and sustainability in the mayor’s office.

So far, Metro has done a feasibility analysis of the light rail corridors — part of nMotion,

here — but much more engineering is needed.

Hafkenschiel said there are fewer choke points — narrow roads or other construction obstacles — than Metro initially anticipated. Also, TDOT will need to be involved in any roadway design changes, and they have so far said that they want to maintain two lanes of car traffic on each side of the center light rail.

5. What are the travel times on light rail between different areas of Nashville?

The proposal includes light rail and rapid bus travel times on

pages 16 through 25. The times shown are from one end of the line to the other.

For example, the light rail line that connects downtown to the Nashville International Airport would make its 8.6-mile trip in 26 minutes.

Hafkenschiel said that travel time, by the year 2040, would be “30 minutes faster than a bus would be and 15 minutes faster than driving.”

6. Will I be able to take my bicycle on the light rail?

Yes.

Paying For Transit, And Other Questions

7. How much, specifically, will our sales tax increase? Is this on all sales (including grocery)?

WPLN recently detailed the sales tax part of the proposal,

here.

The total sales tax is currently 9.25 percent. It would go up to 9.75 percent for 4 years, and then rise again to 10.25 percent after that, if the referendum is approved.

Groceries are currently taxed a little lower, at 6.25 percent. That would go up by the same amount.

8. Will the property taxes be raised in Davidson County?

No.

9. How is the plan addressing the daily in-migration of people from surrounding counties who work in Nashville? What about park-and-ride areas?

Metro’s plan makes the case that transit could keep thousands of Nashville residents’ cars off of the streets and interstates each day, helping the flow of traffic.

Hafkenschiel also said that a large share of downtown trips are not attributable to out-of-county commuters.

“People feel like people are coming into downtown from our surrounding counties and that’s causing a lot of our congestion. But it’s actually 40 percent of commuters into downtown are coming in from outside of our county, so 60 percent of them are coming from inside the county,” she said.

Hafkenschiel points to

annual surveys of downtown employees by the Nashville Downtown Partnership, which showed last year that 63 percent of downtown employees live within Davidson County.

“Think about how it is when school is out of session,” said Hafkenschiel. “You notice a noticeable difference in travel times.”

The Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) finds that the percentage of workers in neighboring counties who commute into Nashville decreased between 2000 and 2010, although the raw numbers of travelers has increased (

MPO page 6).

For background reading on travel patterns, the MTA’s nMotion plan provides details on page 60,

here.

As for park-and-ride lots, the plan calls for those, but the exact locations are not yet determined. The nine high-capacity routes would each have a park-and-ride at the far end of the line (see map on

page 14).

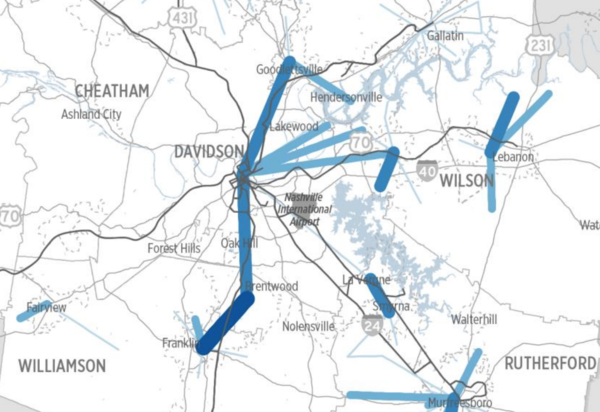

Hafkenschiel and Bland envision that the Regional Transit Authority’s existing 10 bus routes could bring people from surrounding counties into the city, with the option for passengers to transfer to rapid buses or light rail to move more quickly through the densest downtown congestion.

Editor’s note: This answer has been corrected to fully reflect Hafkenschiel’s statements about the origins of traffic in downtown Nashville, to cite her source, and to add context from MPO research. WPLN’s original answer imprecisely referred to “interstate loop” traffic.

10.

If it passes, will the city be locked into the expensive and inflexible hub-and-spoke plan?

The answer, in short: Yes. The city has had and will continue to have a hub-and-spoke system, meaning that a majority of transit trips are directed into downtown, requiring transfers onto other routes for many passengers.

None of the local, state or federal planners or transportation agencies have proposed an alternative.

Bland, with the MTA, said that Middle Tennessee’s topography, growth history, commuter patterns, and the growing vibrancy of downtown Nashville are all factors that

necessitate a hub-and-spoke system.

“Nashville’s mobility network is a hub-and-spoke system,” Bland said. “If you don’t deal with the hub, it almost doesn’t matter what you do in the ring counties.”

There are some exceptions to the hub-and-spoke flow. The MTA has long acknowledged that downtown transfers add to travel times and has started adding some “crosstown” connector routes.

The transit proposal going to voters would add four new crosstown routes in 2019 (see

page 12) along Trinity Lane, Edgehill Avenue, Bell Road and a connection between Opry Mills and the airport.

Bland said that the transit proposal would allow for more frequent pickups on buses and rail, including in downtown, so that transfers would become faster — so, still a hub-and-spoke, but one projected to have shorter travel times.

11. Is it accurate to say the mayor is the primary person in charge of overseeing the implementation of this plan? If not, then who is?

Not really.

Although former Mayor Megan Barry was seen as the face of the plan, the mayor’s office wouldn’t be carrying out the implementation. Metro Public Works (and the Division of Transportation that would likely be created within it) would be responsible for the actual construction and road project management — and the MTA would be the operator of the services.

There is still a role for the mayor and the Metro Council. Agencies like Public Works and the MTA would still go through the normal budgeting process: sending proposals to the mayor, who writes a proposed budget that the council reviews and votes on.

_