There’s a small area of downtown Nashville – about 5 square blocks – that says a lot about how neighborhoods get their names.

These days, it’s SoBro. But 130 years ago, it was Black Bottom.

As part of Curious Nashville, WPLN went looking for this thread of history because of a question from Larry Prendergast.

“Where was the Black Bottom and why was it called that?”

The available evidence about Black Bottom provides a window into a great deal of change in Nashville – and into a time of shrill racism.

Soil Or Skin Color?

There are two competing theories about the name “Black Bottom.”

Theory One: Geography.

The most readily available theory appears at the top of online search results.

The area south of Lower Broadway was, physically, the low point in downtown, and an exceptionally flood-prone place from the Cumberland River up to about Fifth Avenue (which went by another name at the time).

Metro Archives

Metro Archives For about 100 years, the area south of Broadway in downtown Nashville was known as “Black Bottom.”

Tennessee State University historian Bobby Lovett writes that the area got its name from “frequent flooding and the ever-present black mud and stagnant pools of filthy water,” caused in part by the river and partly from water coursing forth from Wilson Spring Branch, a creek that was later bricked over as a sewer.

Historian and former state lawmaker Jim Summerville also describes the area as having “soil … much darker than the clay and mineral-laden earth” elsewhere in the region – although he concedes that historians don’t have much to go on from that era.

Theory Two: Racism.

Simply put, from the 1880s to the 1920s, hundreds of newspaper articles recount crime, prostitution, and debauchery in Black Bottom – along with aggressively racist schemes to redevelop the area. There were frequent references to its residents as, essentially, the lowest of the low in the city. There came a point when “Black Bottom [racial slur]” became a demeaning way to reference its residents as their own class.

So in understanding this time period, the name is no small matter. And eventually it became clear how entwined “Black Bottom” was with race.

But tracking the origin of the name isn’t easy.

Vetting The Theories

Lovett, the TSU historian, goes so far as to discount the race theory.

“In my opinion, it wasn’t because it was a black area. It was just a bottom area. And bottom areas in cities tend to be the poorest areas,” he told WPLN. “By the 20th Century, it did have the (racial) connotation. It was poor and black.”

At the core here is a question of when – when did the name appear?

Local history buff David Ewing says he doesn’t believe the black soil argument because “Black Bottom” appears to have taken on that name after the Civil War, when poor African-Americans moved into the area.

“Look when they called it that, and look who lived there,” Ewing said. “If you read how Black Bottom was described in the newspaper back then, it wasn’t about soil.”

At Ewing’s suggestion, we reviewed several local history books and browsed hundreds of “Black Bottom” references in digitized stories at newspapers.com.

The earliest reference seems to appear after the Civil War, in 1873 – although in that mention, the reporter referred to a different dirty pond north of the state capitol.

Jump to 1878: The “Black Bottom,” south of Lower Broad, had become a staple of the crime blotter because of the people and activities there.

“The Horrors of Black Bottom” and “Vile Black Bottom: The Worst Spot In Nashville…” are just two early headlines that go on to detail ramshackle tenements, vagabonds and convicts loitering in the streets, and wanton prostitution.

Racism pervades news clippings for the next four decades.

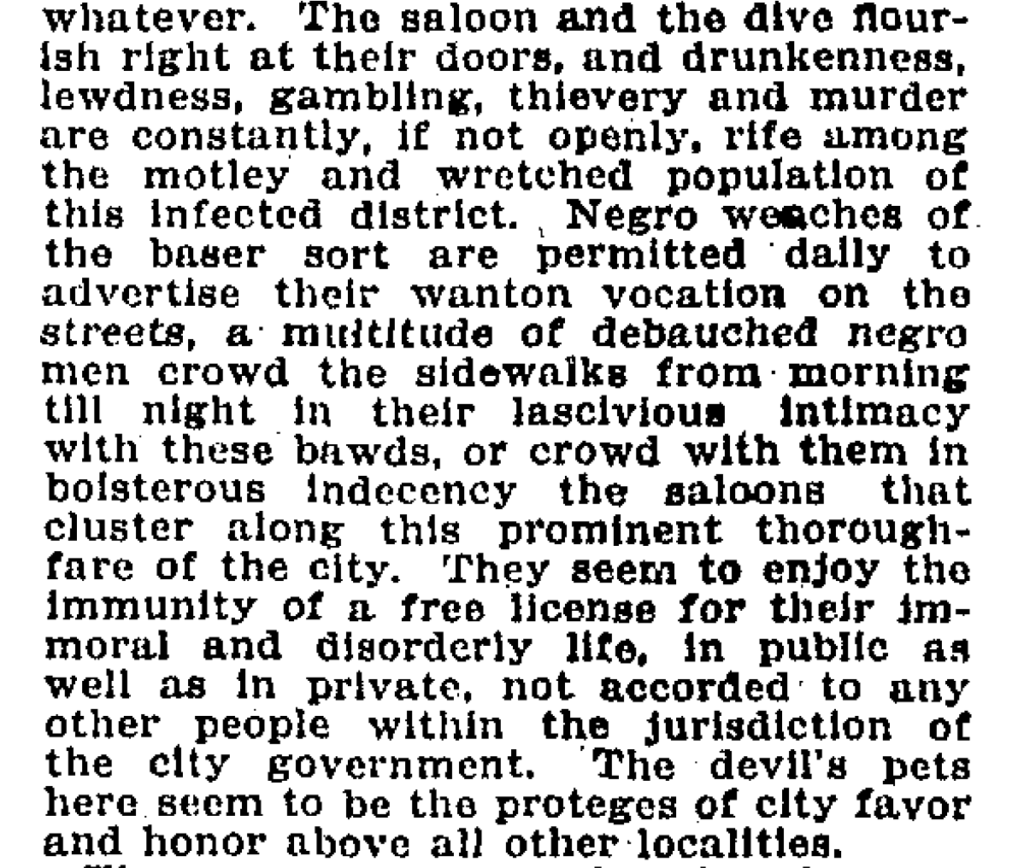

In the following excerpt from The Nashville Tennessean in 1905, a letter to the editor suggests the English language cannot capture the “hell-hole” of Black Bottom – but goes on to try anyway.

newspapers.com

newspapers.com Black Bottom described in June of 1905.

Across the board, historians agree that Black Bottom was a rough place to live, with copious saloons and brothels, outdoor bathrooms, and coal-heated homes that left a haze in the air and “black soot covering everything,” according to Lovett.

Yet there’s also disagreement about who exactly was living in Black Bottom.

Historian Don Doyle writes: “The worst of these slums was an area known as Black Bottom … filled largely with blacks, as its name implied, the area was home also to a fair number of poor whites and Irish and Jewish immigrants.”

Lovett cites city directories that show about half-and-half poor white immigrants and recently freed, working-class African-Americans living in what was then the Sixth Ward.

Yet the ward had wider boundaries than the looser conception of Black Bottom, so those counts come with a caveat.

And it’s worth noting how perceptions of distance change over time. In the late 1800s, traveling just a couple blocks could take someone from the distress of Black Bottom to the affluent Rutledge Hill, just up the slope to the south – an area so easily traversed nowadays by car that it now feels like a single neighborhood.

Selected timeline

- 1888: Overcrowding and disease spur public health worries in Black Bottom and other slums.

- 1893: Some Black Bottom properties condemned.

- 1905: “Black Bottom had become a permanent sore on the edge of downtown.”

- 1907: South Nashville Women’s Federation lobbies for a new park and bridge to “eliminate black bottom.”

- 1910: The idea for a park is defeated.

By 1907, a massive push was on to eliminate Black Bottom.

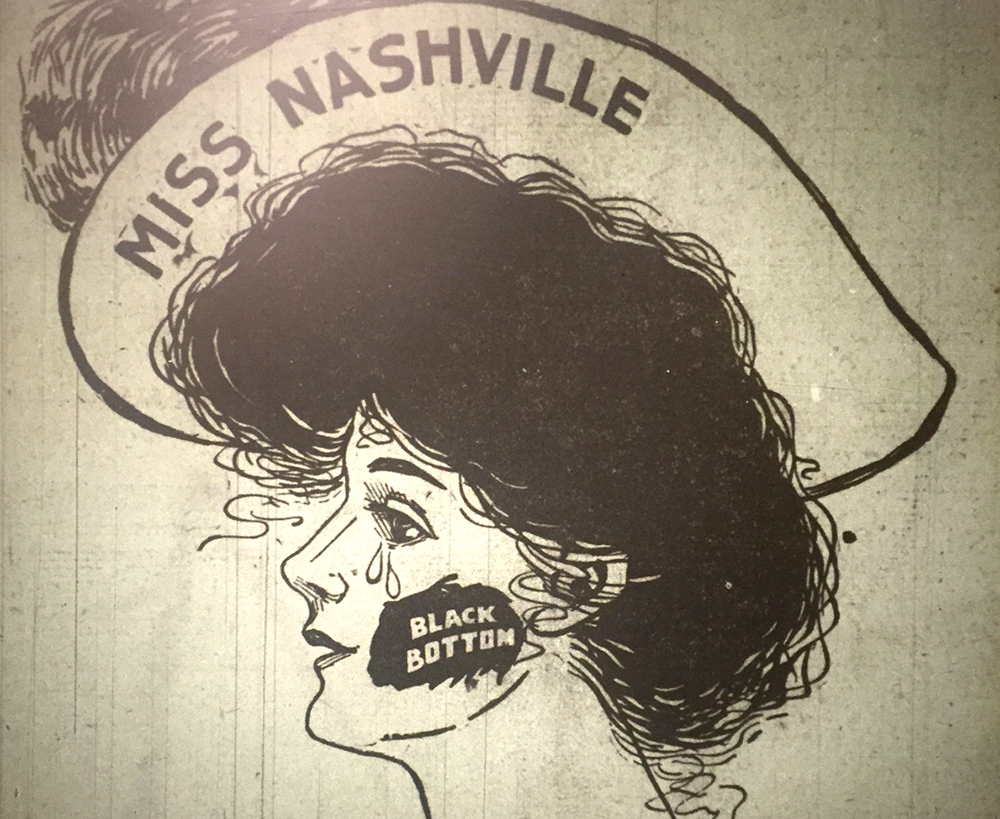

That summer, The Nashville Banner published an editorial cartoon depicting a white woman, “Miss Nashville,” with a black mark on her cheek, “a horrid blemish – cannot the city council concoct the lotion to remove it?”

Nashville Public Library Special Collections

Nashville Public Library Special Collections This 1907 editorial cartoon from The Nashville Banner depicts the city as a woman with a dark blemish on her cheek, and asks what can be done to remove it.

While the park plan was defeated, the bridge that now stands as John Seigenthaler Pedestrian Bridge was built, beginning the displacement of Black Bottom. By 1912, shanties were being displaced by new construction and some were touting new business activity as the best, or, “the only way in which Black Bottom could be eliminated.”

Reviewing the theories – soil and skin color – provides evidence for both. The geography and filthy floods cannot be denied. But neither can the fact that the place became its own local racial slur.

A New Name

Lovett reports that New Deal programs skipped over the area, but later urban investments from the 1950s through 1970s brought in “wrecking balls, bulldozers, new highways, broader avenues, redevelopment projects, and commercial zoning policies.”

Nina Cardona WPLN

Nina Cardona WPLNIn May 2010, the area now known as SoBro demonstrated its geographic disadvantage – being the low point of downtown.

Fast forward to the mid 1990s. A history of the area written by the Nashville Civic Design Center attributes the coining of a new name, “SoBro,” to The Nashville Scene.

At the time, there was controversy surrounding a potential six-lane road to be paved across the southern portion of downtown. Eventually, it became the narrower Korean Veterans Boulevard.

SoBro – “south of Broadway” – makes a play to encompass a broader area than Black Bottom ever did. Yet some smaller pockets have managed to carve out their own names.

Rolling Mill Hill, for example, rises to the southeast along the bluff of the Cumberland River. The Civic Design Center attributes the name to long-gone flour mills there.

And the wedged streets between Lafayette Street and 8th Avenue South have coalesced around the name Pie Town.

It’s too soon to say whether those monikers will stay – or become Curious Nashville questions of the distant future – but their origins may be better documented than Black Bottom.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))