There’s something about past mayhem that intrigues people. Hence, this question submitted to Curious Nashville:

What is the history of the Nashville reservoir flood, and what is the reservoir’s use today?

The reservoir in question is the 8th Avenue Reservoir.

It’s one of 39 across Davidson County these days, and it has been the biggest ever since its completion in 1889. It is still in use today, holding some 25 million gallons of clean drinking water.

What has changed is how closely the reservoir is monitored, mostly because of the aforementioned reservoir flood more than 100 years ago.

‘Small Leaks Appear… Nothing Serious Unless…’

By July of 1888, a crew of more than 550 was hard at work on the reservoir on Kirkpatrick Hill in South Nashville. The noisy endeavor to build the “finest by far in the South,” included immense amounts of blasting and the steady sound of work songs, as described by The Daily American newspaper.

“The new reservoir has begun to loom up in great proportions, and the giant elliptical walls, looking somewhat like the ruins of the Roman Coliseum, can be seen from every hilltop and from every eminent point in and around Nashville.”

It was 603 feet across, with walls 22 feet wide at the bottom, and the capacity to hold 51 million gallons of water, according to this detailed history by Metro Water Services.

The “stupendous structure” was completed in 1889 and began its work of filtering water from the Cumberland River in the old-fashioned way known as “settling.” River mud would sink. Because the reservoir is divided with a center wall, the clean water on top of the settling tank would be transferred through valves to the other “clean” side.

Not long after opening, an October 1889 article describes small leaks as “nothing very serious unless they grow larger.”

“A mild rumor went floating about town yesterday that the new reservoir was leaking,” the Daily American reported, “and as the hood of the valve in the main on Fillmore Street at Wharf Avenue flew off and flooded the street, a small-sized excitement boom sprang up.”

‘Remarkable Escapes From Death’

Some mistook the crack and rumble for a tornado.

And as Nashvillians near the reservoir climbed out of bed, the deluge swept through what is today’s Edgehill neighborhood along 8th Avenue South just after midnight on Nov. 5, 1912.

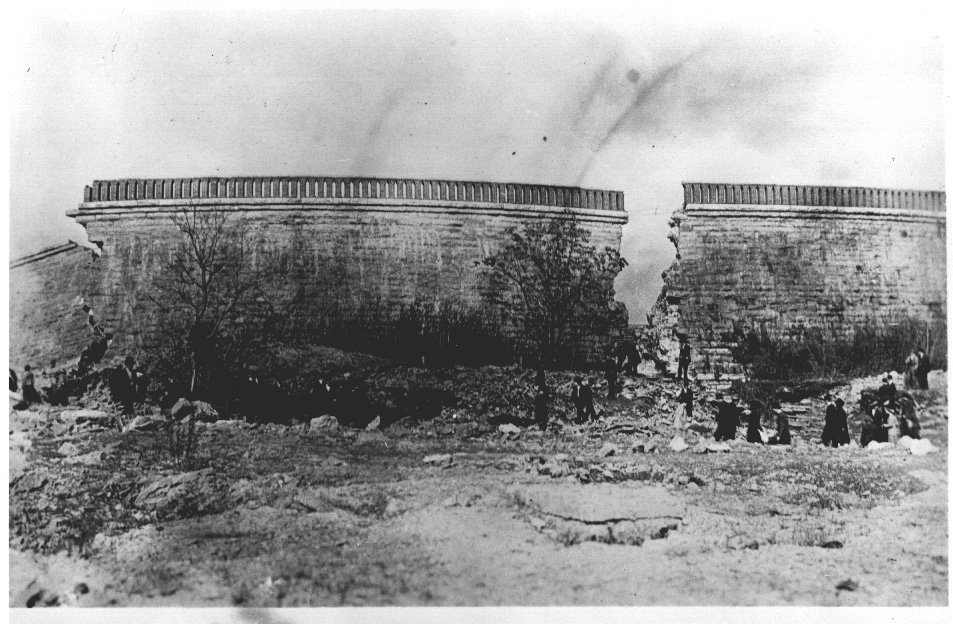

A 175-foot, V-shaped gash had opened on the southeast side of the reservoir above, sending a flood of water and mighty stones cascading down.

Newspaper accounts say a pair of streetcars had just left the area and narrowly avoided destruction. But the deluge destroyed five homes — sweeping three off their foundations — and damaged another 20. Telephone poles, furniture and at least one chicken coop also washed away.

Yet no lives were lost.

TSLA

TSLA The section of wall that shifted and cracked was in the southeast quadrant of the reservoir.

Investigators came to believe that leaking water gradually dissolved clay near the base of the wall, allowing it to settle until it cracked, according to Metro Water.

Local historian George Zepp wrote in his book “Hidden History of Nashville” that the disaster led to concrete reinforcement of the reservoir. He also recounts a prominent naysayer who had, years earlier, opposed the location for the reservoir and predicted its failure.

That mantra was picked up again, and by June 1913, one newspaper editorial proclaimed 12 reasons the reservoir should be removed and relocated.

That argument did not win out.

TSLA

TSLA An aerial view of the reservoir and Nashville in September of 1940.

The structure was relined in 1921. In the mid 1970s, it got steel reinforcements and bedrock anchors. And to this day, the walls and surrounding soil are closely monitored for seepage and movement.

Today’s Reservoir

These days, there’s no mud settling out of the water in the 8th Avenue Reservoir. Sonia Allman, spokeswoman for Metro Water, says it is only used for storage of treated water — typically 17 to 21 million gallons that are kept in the eastern half.

That water is pumped to homes and used by firefighters in the low-lying areas of Nashville known in Metro Water terms as “city low.”

And it’s still the biggest.

“Because it was built in the 1800s, it was the one and only. So it was much larger than what you would think of as a reservoir now,” Allman said

Among the changes since the reservoir’s beginnings:

- Only half the capacity is now used.

- The treated water is covered to defend against birds and debris.

- Security has increased.

- The “gatehouse” is unoccupied.

Allman talks with enchantment about the gatehouse on the rim of the reservoir. The ornate little building, complete with interior fireplace, was used as a control room for valves that are no longer needed.

There’s little daily activity at the site other than the work of guards, which Allman says is necessary to protect the drinking water. In fact, she says the department doesn’t often share about the reservoirs, out of caution.

“A 51-million-gallon rock reservoir on a hill … it doesn’t get as much as attention as you would think it would,” she said.

Metro Water prefers it that way. But as evidenced by the number of websites dedicated to Nashville’s historical disasters, there’s no good way to tamp down interest in places with such intrigue.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))