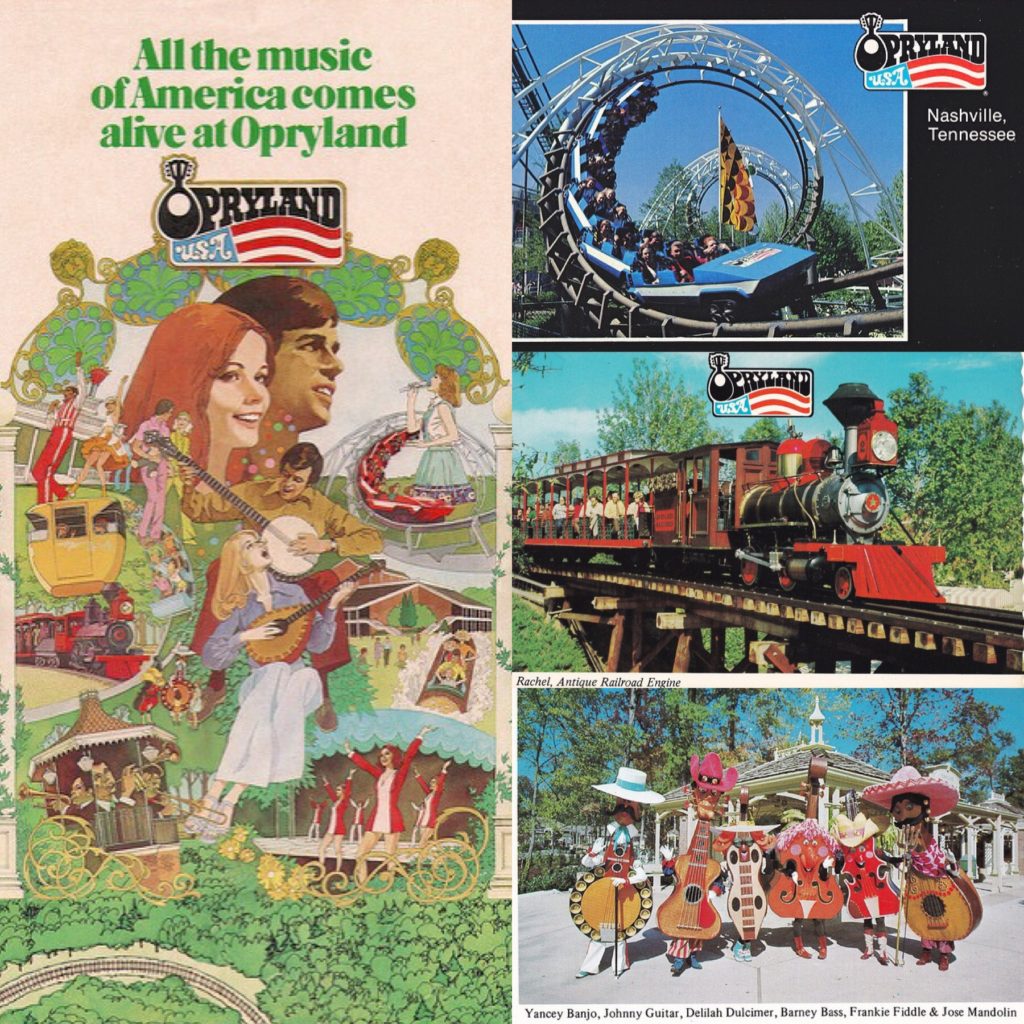

Twenty years ago, Nashville had a theme park.

Opryland USA sat in a curve of the Cumberland River now home to a giant mall. It had roller coasters, Southern-themed restaurants and live country music revues. Memories of rides like the Screamin’ Delta Demon are still traded like gold among longtime Nashvillians — as are the rumors of why it all went away.

That was what some listeners asked about in Curious Nashville:

Why did Opryland close?

The answer is as murky as the waters of the Grizzly River Rampage.

The first thing people assume about the closing of Opryland is that the park was losing money. Recent visitors to Opry Mills Mall buy into that theory: One said he had heard it was “underperforming,” while another visitor assumed it lacked the amount of business to keep it “viable.”

But while attendance had been down slightly in the years leading up to the closing, the man who ran the business for most of its history says money was not the problem.

“Opryland was successful. And it was successful when they shut it down. We weren’t losing money,” said former Gaylord CEO Bud Wendell.

Wendell stepped away from his post early in 1997, and months later, new leadership decided the park should be scrapped in favor of a new fad: shoppertainment.

Here’s comedian Kathy Griffin in a TV ad from 2000 pitching the concept:

Wendell is not shy about his opinion of that decision.

“Dumbest thing I’ve ever seen,” Wendell states. “And the people that were responsible for it, I would think today would look back on it and say, yeah, it was a dumb, dumb decision. But they felt they could get a greater return on that piece of acreage out there if it were a mall as opposed to a theme park — America’s only musical theme park.”

The people responsible for turning Opryland into Opry Mills Mall included the man who filled Wendell’s shoes for a few years, Terry E London. In addition to the mall, London had another vision for Gaylord — corner the market for Christian music online.

The entertainment world was in the middle of an internet land grab and after selling the park, London had Gaylord buy up Christian music dot-coms. But the internet bubble burst and London was pushed out as Gaylord’s fortunes plummeted far below where it had been when the theme park was still open.

At the time of the park’s closing, London told local media that Opryland would not be able to keep up with high tech investments by other parks but its closest competitor, Dollywood has survived. A recent study by the Pigeon Forge-based entertainment complex shows it has an annual economic impact estimated at more than $1.5 billion.

Beyond the monetary benefits to Nashville’s tourism industry that Opryland might have had were it still operating, Wendell says the city really misses another important aspect that came along with the park.

“We hired about 4,000 young people — you may have been one of them — every year. We trained them. We watched carefully over ’em. We had activities for ’em. They had their own ball teams. We had dances.

“And that disappeared just like that. Jobs. For 4,000 youngsters. Nobody ever thought about that. Nobody I guess still ever thinks about it.”

Wendell says at least once a year he’ll hear rumors about some group or other who say they want to build a new park. But nothing has come of it.

At least, not yet.