A Black boy named Samuel Smith was lynched by a white mob on Dec. 15, 1924. Despite a grand jury investigation, public outcry and a reward, no one was ever charged. Now, a new marker at the site of Davidson County’s last known lynching aims to share Smith’s story.

15-year-old Smith, a Rutherford county resident, and his uncle, Eugene, were driving when their car broke down. Eugene left his nephew with the car, as he attempted to take car parts from a nearby home where Nolensville grocers Ike Eastwood and his brother lived.

It isn’t clear who shot first, but Samuel ended up at Nashville General Hospital while Eastwood went to Saint Thomas hospital.

At least six armed and masked white men walked into Nashville General looking for Samuel, who was chained to his bed under police custody. Nurse Amy Weagle tried to cover up the chain in hopes of preventing the kidnapping, but Samuel was still kidnapped and driven to Frank Hill Road, which is now Old Burkett Road.

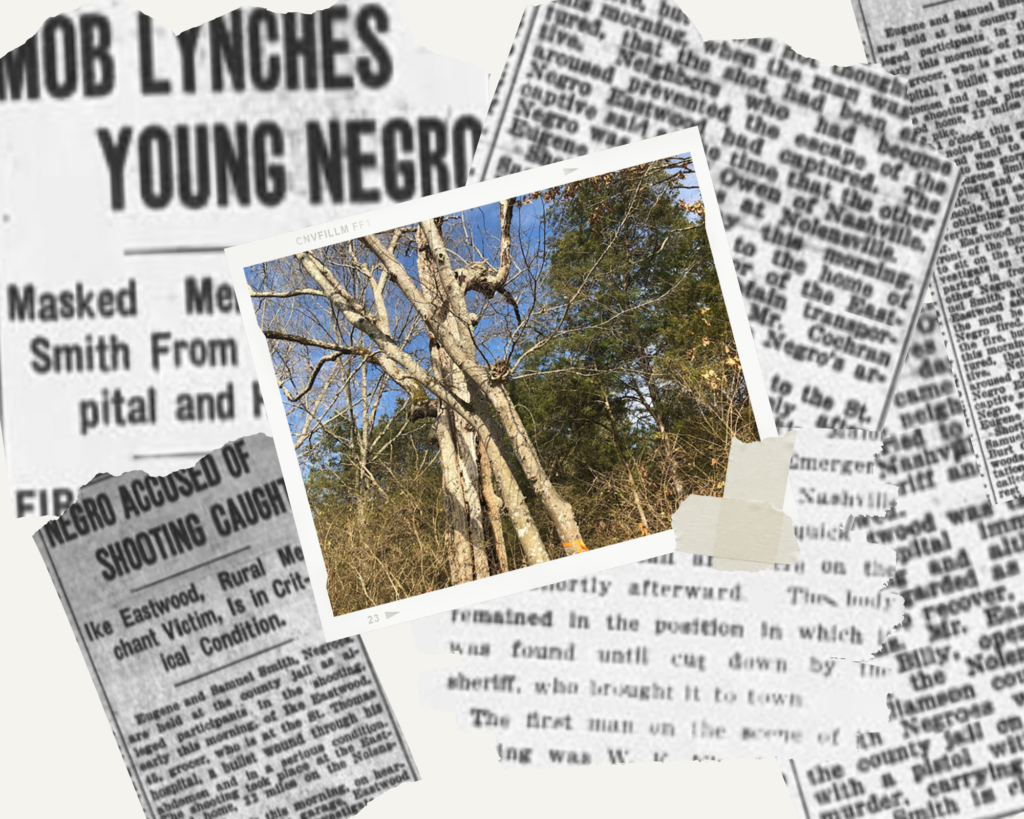

Near the alleged robbery and shooting, the white men stripped Smith of his pajamas, hanged him from a tree with a thin rope and shot him multiple times.

In the century after the Civil War, thousands of Black people, including children, were lynched. White people used public violence to deny Black Americans their rights and punish people who didn’t follow the racial hierarchy.

“The reason Samuel Smith was lynched was to send a message to the African-American community in Nashville, in Rutherford County, in Williamson County and anywhere around that area where people would hear about it,” Metro Historic Preservationist Jessica Reeves says. “I know that this lynching was publicized in newspapers as far away as Minnesota. So, it was really just part of this larger narrative.”

Now, the Metro Historical Commission will recognize the last known or recorded lynching in the county with a historical marker.

“It’s people who repeat history,” Historical Commissioner Linda Wynn said just before the Monday vote. “This is a history we should not want to repeat.”

Commissioners had the support of some community members. While others, including descendants of the Eastwood family, felt the history shouldn’t be discussed or acknowledged publicly.

“We did hear from at least one of his family members who felt as though the marker was for someone who severely wronged their family and thought that there shouldn’t be a marker for something like that,” Reeves explains.

Nashville’s two existing historical markers recognizing lynchings are located on 1st Ave N near Woodland St. Bridge. They were sponsored by We Remember Nashville and the Equal Justice Initiative.

There are plans to install two more markers in Germantown and North Nashville. The Commission will sponsor one more lynching marker in Bellevue, which will publicly recognize all known lynchings in Nashville. Statewide, there were over 200 documented lynchings in Tennessee.

The Samuel Smith marker will be installed this winter near the tree where Smith was lynched.