Rodney Northington is an unlikely person to be telling folks who live in the James Cayce housing projects to put down their guns. He’s a convicted felon, a former drug dealer and at one-time a high-ranking gang member. But he’s also, quite possibly, the perfect man for the job.

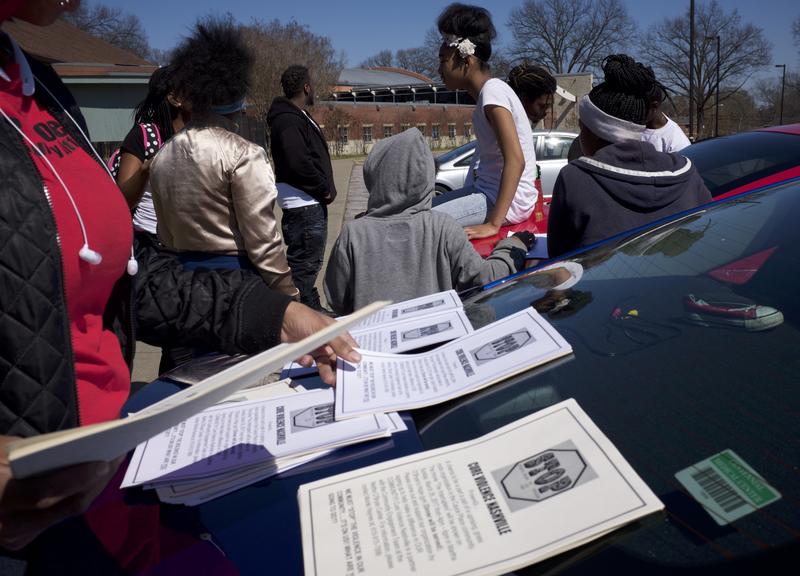

It’s a sunny Sunday afternoon, and Northington is going door-to-door in the city’s largest subsidized housing complex. He’s handing out flyers advertising his new program based on Cure Violence. It’s a concept that began in Chicago. One that treats violence like an infectious disease that can spread within a community, and the treatment comes from those who once caused it.

“I can walk around this neighborhood and knock on every door,” Northington says. “Because I’m here, and I got respect.”

Northington, who is 27, lives in Cayce. He’s tall, thin and walks in graceful long strides. As he makes his way through banks of low-rise apartments, he can barely go a few steps without stopping to greet someone.

“They look up to me. And they listen to me,” he says. “If I told these people let’s do something bad right now they’ll do it. So why not tell them to do something good?”

This is the essence of the theory behind Cure Violence — that people like Northington can do things, go places, and touch people in a way that the police simply cannot. That they can quickly diffuse tension and stop retaliatory shootings before they happen. That they can interrupt the violence. Northington and Haynes call themselves “violence diffusers.”

Northington’s partner in his mission is 32-year-old Monte Haynes, also a former high-ranking gang member turned interrupter. He grew up in Cayce. And since getting out of prison in 2011, Haynes went back to school for business. In his free time, he worked to mediate conflicts that arise on the street. It’s a far cry from what Haynes was known for in the past.

“It would amaze them to see a guy who they used to see running around with a gun, running from the police, bagging up weed,” Haynes says. “It shocked them to see me doing something different.”

Haynes and Northington say Cayce needs this program more than ever. Assaults are up in the neighborhood. Across the city, homicides are the highest they’ve been in a decade. As we walk, Northington notices how few people are out, enjoying the nice weather.

“That’s because people done got killed and people in jail,” Northington says. “Most people are really scared of two things: They’re scared of each other and they scared of the police.”

The relationship between Cayce residents and law enforcement has been tense over the last couple of years. There were two assaults on officers, and last month a man was shot by police in the complex.

“I really want to prove to these people that if we change our environment ourselves, we won’t have to worry about the police coming through and harassing people,” Northington says.

As the two men zig zag door-to-door, they take the temperature of residents. Are they willing to consider their message? Will they come to an information session?

Some are already on board. One man tells Haynes he put down his gun years ago.

“Hey, I know you with that guns downs movement,” Haynes says.

“You know I am. I been guns down for three years,” the man replied.

But others, require a little more coaxing. Northington talks to one Cayce resident who ventured out onto his stoop.

“You’ll be a big influence on the community,” Northington says to him. “They see your face out here every day. When they see us do different they’ll do different. You feel me?”

The man nodded, assuring him he’d be at the info session. “You know I’ll be there,” he says.

As they walk, Haynes comes upon a group of about five men, standing in a circle, drinking Hennessey cognac from a bottle. Enjoying the weekend afternoon. They quickly hide their liquor with puzzled expressions.

“All we want you to do is put your guns down,” he says. “We don’t care nothing about you smoking no weed, selling no dope.”

Some are struggling to understand the concept. Though it clicks for one of the men that all they care about is violence, nothing else.

“It’s the violence brother. That’s what you’re trying to get hold on to, the violence,” he exclaims.

The Diffusers walk a fine line. Neither Northington nor Haynes will tell someone to stop trying to make their living, even if it means breaking the law. They just want the shooting to stop.

“I mean, if you’re going to gang bang, gang bang right,” Haynes says. In other words, do it in a way that doesn’t put others at risk. Do it without the guns.

Overlooking other unlawful behavior is the double edge of this type of strategy. It makes it hard for the police to get behind the mission. And it can be touchy when cities use public money to pay convicted felons for mediation.

But places like New York have embraced Cure Violence,

investing millions. And last year, it saw the lowest level of

gun violence in more than 30 years.

The Nashville group is still a nascent organization with no official link to the Chicago-born organization. They don’t have any official funding or even an office.

As they walks the last block of their canvas, Haynes plays rap music from his phone through a bullhorn. Most of the flyers are gone. Board member Lita Russell works on logistics. The group has plans to have interrupters post up around Cayce, so they can be ready to diffuse potential disputes.

“That field right there,” Russell says, pointing. “It be popping in that field right there. Let’s put a post right there.”

Overall, the response is good. Only a few residents waved them off. As they climb South 7

th street, interrupter Marque Collins, approaches two young boys riding bikes. He tells them to come to an event and watch a documentary.

“But guess what you probably know the violence probably won’t stop,” one says. “I’m just saying.”

“We got to start curing it somewhere,” Collins says. “And it starts with the young.”

There is skepticism that anything could cure the violence that has spanned generations. And with that the boys are off, grabbing a flyer before zipping down the hill on their bikes.

*This story has been updated to reflect that the group’s working title is not yet approved for use by the Cure Violence organization.