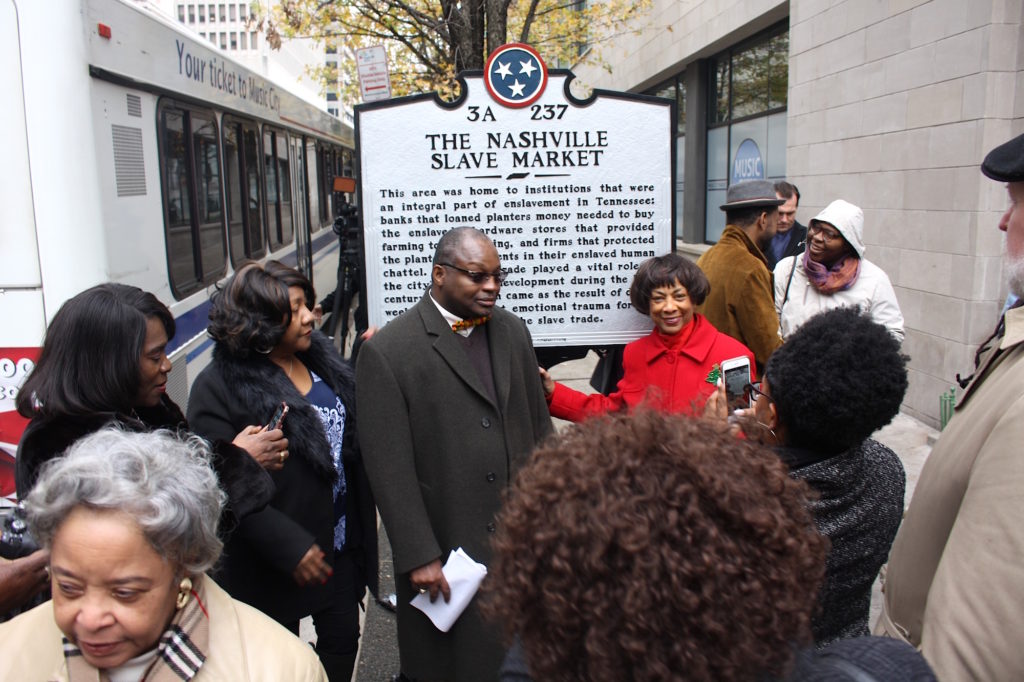

For many, Nashville’s newest historical marker is long overdue.

About two blocks west of City Hall, the sign describes the Nashville Slave Market as a place of profit-driven trauma for the African-Americans who were sold there, and it explicitly links slavery to the city’s early prosperity.

“I wonder what it reveals to us, as a city and a state, that it could take 153 years to take a public statement that affirms their humanity, that gives value to their lives, and that recognizes the effect that their sale had on us as individuals and as a city?” said Tennessee State University associate professor Learotha Williams, who was encouraged by a group of students to campaign for the marker’s creation.

Williams spoke to several dozen who gathered on Dec. 7 for the unveiling at the corner of 4th and Charlotte, and he called attention to the city bus station that was their backdrop.

“This has always been a transfer point. Today we might catch a bus,” he said, “but 150-some-odd years ago, people were forced to come here.”

Humiliation And Grief

Through his research, Williams found stories of children as young as 7 sold at the market, women sold as sex slaves, and hundreds routinely forced to strip naked and roll down the hill to prove their health.

By 1860, free and enslaved blacks comprised 26 percent of the city’s population.

“What effect did the auctioneer’s call have on them, when they heard them scream ‘sold?’ ” Williams asked. “How did they respond to the fervent prayers that they must have heard coming from these spaces?”

Williams was joined by Reavis Mitchell, Jr., professor at Fisk University and chairman of the Tennessee Historical Commission. He emphasized the business infrastructure that surrounded the market — “one of the first great business opportunities in Tennessee” — and its proximity to government institutions.

“That business was buying and selling people who looked like me,” Mitchell told the crowd.

‘Difficult Truths’

Nashville now has six markers that reference slavery, out of more than 160, bringing some light to stories that are still underrepresented, said Davidson County Historian Carole Bucy.

“We put all of those stories in a box, tossed them in a very deep well and pretended that it never existed. … It was a sin of omission,” Bucy said. “With the unveiling of this marker, Nashville begins the process of making our story more complete and more honest.”

More: See a map of Nashville markers

Statewide, there’s been a push for black history markers since 1987, when the state counted those that existed and found just 12 that had any reference to African-Americans. A concerted effort has since increased that count to more than 200, said Tennessee Historical Commission Executive Director Patrick McIntyre.

“This marker we’re about to unveil is the most important, significant one during my nearly dozen years as executive director,” he said. “History has many difficult truths, and we must be willing to acknowledge these and learn from them.”

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))