Drought affects everything from water quality and public health to ecosystems and infrastructure. But when does a drought become severe enough to warrant water restrictions?

Tennessee state agencies do not have that answer, according to a new report funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of South Carolina.

The state last released an official “Drought Management Plan” in 2010. It outlines a general approach to monitoring, water management and agency coordination during drought, but it lacks the processes needed to determine the severity of a drought and how to respond at different levels of drought.

“It is not an operational plan as it does not specify monitoring indicators nor the threshold values that would trigger drought declaration levels and response actions,” the report states.

Across the state, local water systems are required to have their own drought management plan that includes trigger points. The report warned about responsibilities being “siloed” to the water management sector, since other agencies, including the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Army Corps of Engineers, play important roles in regulating water movement and availability.

The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation and the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency are the agencies in charge of drought preparation, and the governor has the ability to make an emergency declaration that would allow them to take action during droughts.

TDEC said it is still reviewing the report and did not respond to questions about how or when it might update the Drought Management Plan.

Hotter temperatures will cause more rapid droughts

Tennessee state climatologist Andrew Joyner said the drought management plan should be updated soon.

“So much has changed since it was written in 2010,” Joyner said. “There is so much new data and resources available.”

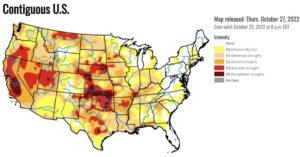

Courtesy U.S. Drought Monitor

Courtesy U.S. Drought Monitor The U.S. Drought Monitor estimated that 84% of the contiguous U.S. was abnormally dry in late October 2022. Nashville’s drought was classified as “severe.”

Joyner runs the Tennessee Climate Office, an agency standard to most states that only officially opened in Tennessee in 2021. This office provides climate data services to various agencies, including the U.S. Drought Monitor, which is a national map of current drought conditions. Joyner suggested that Tennessee’s drought planning document should be updated every five years.

Since 2010, Tennessee has had more droughts to study, like the exceptional drought and wildfire event in 2016, and climate models have become clearer.

Despite climate change making Tennessee wetter overall, the state will become increasingly vulnerable to drought in the coming decades.

“Future naturally occurring droughts are projected to be more intense because higher temperatures will lead to more rapid depletion of soil moisture during dry spells,” reads the most recent Tennessee climate summary from NOAA.

In 2022, Tennessee faced two different droughts. There was the drought in July – which was the second hottest July in Nashville on record – that ended in August. Then another drought started in October, covering the entire state, and only fully cleared the state this past week. (Despite these droughts, Tennessee still ended the year with about 53 inches of precipitation, 2.5 inches higher than the most recent 30-year climate average.)

This most recent drought dropped off just before the state would have needed to confront potential water resource issues for the spring, according to Joyner.