Discharge day for Phoua Yang was more like a pep rally.

On her way rolling out of Centennial Medical Center in Nashville, she teared up as streamers and confetti rained down on her. Nurses chanted her name as they wheeled her out of the hospital for the first time since she arrived in February, barely able to breathe with COVID.

Courtesy TriStar Centennial

Courtesy TriStar Centennial Phoua Yang poses for a photo with the “Yang Gang,” which included many of the nurses who cared for her at Centennial Medical Center. She spent six months in the hospital and 146 days on an ECMO heart and lung machine.

The 38-year-old mother is living proof of the power of ECMO. She’s also an example of why the treatment is so scarce.

“146 days is a long time,” Yang says. “It’s been like a forever journey with me.”

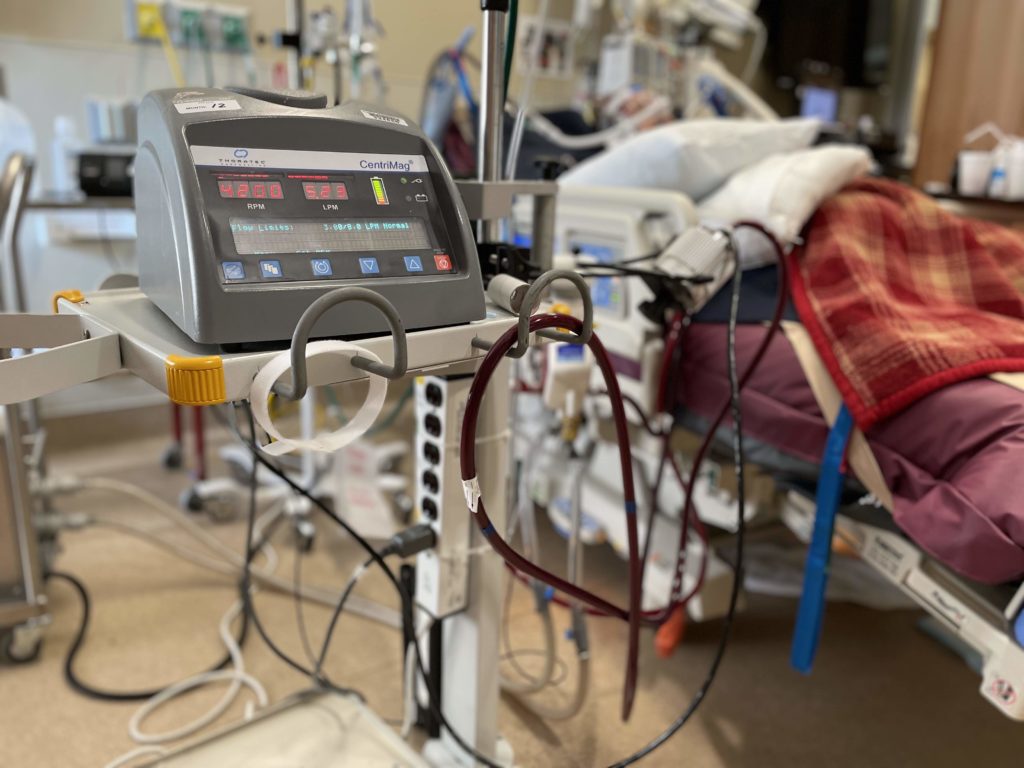

For more than five months, Yang had blood pumping out a hole in her neck and running through the rolling ECMO cart by her bed.

ECMO is the highest level of life support — beyond a ventilator — when the patient’s blood is pumped outside the body to be oxygenated. The acronym stands for “extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” and the machines that perform ECMO basically function as a heart and lungs outside the body. The process, more often used before the pandemic for organ transplant candidates, is not a treatment. But it buys time for the lungs of COVID patients to heal. And that can take a long time.

Many more people could benefit from ECMO than are receiving it, which has made for a messy triaging of treatment that could escalate in the coming weeks as the delta variant surges across the South and in rural communities with low vaccination rates.

Labor intensive

The ECMO logjam is primarily related to just how many people it takes to care for each patient. As their blood is being pumped outside their body through a hole in their neck, they require a one-on-one nurse, 24 hours a day. The staff shortages many hospitals in hot zones are facing compounds the problem.

Yang says she sometimes had four or five clinical staff members helping her when she needed to take her daily walk to keep her muscles working. One person’s job was just to make sure no hoses kinked as she moved, since the machine was literally keeping her alive.

Of all the patients treated in an ICU, those on ECMO require the most attention, says nurse Kristin Nguyen who works in the intensive care unit at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“It’s very labor intensive,” she says the morning after a one-on-one shift with an ECMO patient who had already been in the ICU three weeks.

The Extracorporeal Life Support Association says the average ECMO patient with COVID spends two weeks on the machine. But that includes patients who die while on the machines. Those that survive on ECMO can be on it for much longer.

“These patients take so long to recover and they’re eating up our hospital beds because they come in and they stay,” Nguyen says. “And that’s where we’re getting in such a bind.”

Few hospitals

It’s not that there aren’t enough ECMO machines to go around or the high cost — which is estimated at more than $5,000 a day.

“There are plenty of ECMO machines. It’s people who know how to run it,” says Dr. Robert Bartlett, a retired surgeon at the University of Michigan who helped pioneer the technology and still conducts research.

Every children’s hospital has ECMO, where it’s regularly used on newborns having trouble with their lungs. But Bartlett says prior to the pandemic, there was no point in training a team to use ECMO when they might only use the technology a few times a year.

It’s a fairly high-risk intervention with little room for error. And it requires a round-the-clock team.

“We really don’t think it should be that every little hospital has ECMO,” Bartlett says.

Bartlett says his research team is working to make it so ECMO can be offered outside an ICU and possibly even send patients home with a wearable device. But that’s years away.

Currently, only the largest medical centers offer ECMO, and that means most hospitals in the South are left waiting to transfer patients to a major medical center. But there’s no formal way to do that. And those hospitals have their own COVID patients who’d be willing to try ECMO.

“We have to make tough choices. That’s really what it comes down to — how sick are you, and what’s the availability?” says Dr. Harshit Rao, chief clinical officer overseeing ICU doctors with physician services firm Envision. He works with ICUs in Dallas and Houston.

There is no formal process for prioritizing patients, though a national nonprofit has started a registry. And there’s limited data on which factors make a Covid patient more likely to benefit from ECMO.

Youth changes everything

ECMO has been used in the United States throughout the pandemic. But there wasn’t as much of a shortage early on, when most of those dying were older. ECMO is rarely used for people over 65.

Even before the pandemic, there was intense debate about whether ECMO was just an expensive “bridge to nowhere” for most patients. Currently, the survival rate is roughly 50% with COVID patients — a figure that has been dropping as more families are pushing for life support.

But doctors are more willing to give it a try on borderline patients who are younger — the group that has made up the latest wave of COVID patients.

“I think it’s 100% directed at the fact that they’re younger patients,” says Dr. Mani Daneshmand, who leads the transplant and ECMO programs at Emory University Hospital.

Even as big as Emory is, the Atlanta hospital is turning down requests to transfer COVID patients who need ECMO multiple times a day, Daneshmand says. And calls are coming in from all over the Southeast.

“When you have a 30-year-old or 40-year-old or someone who has just become a parent, you’re going to call. We’ve gotten calls for 18-year-olds,” he says. “There are a lot of people who are very young who are needing a lot of support, and a lot of them are dying.”

Public pleas

Since it’s kind of the wild West to even get someone an ECMO bed, some families have made their desperation public while a loved one waits on a ventilator.

As soon as Toby Plumlee’s wife was put on a ventilator in August, he started pressing her doctors about ECMO. She was in a north Georgia community hospital. They looked 500 miles around.

“But the more you research, the more you read, the more you talk to the hospital, the more you start to see what a shortage it really is,” he says. “You get to the point, the only thing you can do is pray for your loved one, that they’re going to survive.”

Plumlee says his wife made it to sixth in line at a hospital 200 miles away — Centennial Medical Center where Phoua Yang was finishing her 146-day ECMO marathon.

Yang left with a miracle. Plumlee and their children were left in mourning. His wife died August 15, a few days after turning 40.

This story was produced in partnership with Kaiser Health News, NPR and Nashville Public Radio.