The Cumberland Fossil Plant is a coal plant next to the Cumberland River in Stewart County. For 50 years, the Tennessee Valley Authority has burned coal in the rural community near Clarksville — but it plans to shutter its stacks by 2028 in exchange for another fossil fuel.

TVA wants the next chapter of energy in Middle Tennessee to be a nearly 1.5-gigawatt natural gas plant, according to its final environmental review for the proposed plant.

This decades-long decision poses environmental and financial risks. To understand why, understanding how natural gas is extracted and transported is key.

First, you drill, and Tennessee has natural gas drilling sites across the state. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation has granted more than 16,000 permits, dating back to 1968, for oil and gas wells.

But the drilling that supplies Tennessee gas plants likely mostly happens in states with heavy fracking, which is linked to a multitude of health problems. Children living near Pennsylvania fracking wells are two to three times more likely to be diagnosed with childhood leukemia linked to contaminated drinking water, and elderly people living near or downwind of fracking sites are at a higher risk of premature death than seniors who don’t live near gas operations.

Drilling is also a major contributor to global heating. The top 14 individual climate polluters in the world are oil and gas fields, according to satellite data from Climate Trace. The Marcellus Formation, which is concentrated in Pennsylvania but technically stretches into Tennessee, accounts for about 21% of all U.S. gross natural gas production — and it ranked third.

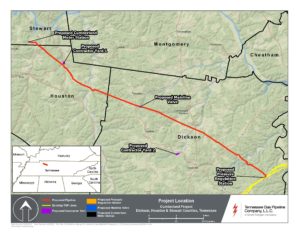

Extracted gas is then pumped through pipelines. To build a gas plant on TVA’s current coal site, the utility needs a 32-mile gas pipeline extending through Stewart, Houston and Dickson counties to connect to other pipelines.

This proposed pipeline will parallel the high-voltage transmission line owned by TVA. It cuts through land owned by people like Rob Connor.

This proposed pipeline will parallel the high-voltage transmission line owned by TVA. It cuts through land owned by people like Rob Connor.

“From a permitting standpoint, it’s probably much easier for them to get the permits for this,” Connor says. “But from an engineering and safety standpoint, this is the worst place to install a pipeline.”

Connor is not just a concerned resident. He is an engineer who spent decades overseeing pipeline projects for Chevron, and his job involved ensuring pipeline safety.

Corrosion is his main concern with the proposed pipeline. The electric current flowing through a transmission line can corrode a nearby pipeline, and corrosion is a common cause of pipeline failures, which sometimes lead to fires or explosions.

Pipelines cause fatalities every year. From 2002 to 2021, gas pipeline failures resulted in at least 227 fatalities and 1,000 injuries.

“I certainly wouldn’t want to have a home within 500 feet of this gas pipeline,” Connor says. “Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t have a choice to have pipelines put by their home.”

Tennessee doesn’t have a required setback between pipelines and buildings, and Gov. Bill Lee signed a law this year that removes local power to regulate pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsA ‘NO TVA PIPELINE’ sign sits in the yard of a Dickson County resident.

Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, which is owned by Texas-based Kinder Morgan, is in a precedent agreement — basically a preliminary contract — with TVA to build this pipeline, which will require the clearing of some trees for construction. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which briefly said it would consider climate change more closely when approving pipelines last year before backlash from companies like Kinder Morgan, will have to approve the pipeline.

Pipelines do have significant climate impacts. Natural gas is mostly methane, which is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in a 20-year timeframe, and it can leak from pipelines.

Methane leaks likely underreported

TVA acknowledged the upstream emissions of methane in its environmental review for its proposed gas plant. The utility cited an American Gas Association estimate that upstream methane releases account for 1% of total emissions and claimed that fossil fuel companies are mitigating the problem.

“Methane emissions from leaks in the natural gas production and transport sectors are being addressed in the natural gas industry,” TVA said in its environmental review.

New research challenges this idea. A study earlier this year of satellite data showed that methane emitted by oil and gas facilities during leaks or maintenance operations comprise roughly 8% to 12% of all oil and gas methane emissions — suggesting that this form of climate pollution has been underreported by the industry.

Courtesy Tennessee Valley Authority

Courtesy Tennessee Valley Authority The Tennessee Valley Authority’s Cumberland Fossil Plant, a coal plant, produces the most greenhouse gases of any facility in the state.

Earth reached record-high levels of methane last year, as well as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. The planet is on track to break more records this year.

Scientists have warned that every tenth of a degree of warming impacts people and ecosystems, while bringing the planet dangerously closer to climate tipping points.

“Droughts, floods, storms and wildfires are devastating lives and livelihoods across the globe. Loss and damage from the climate emergency is getting worse by the day,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said during last month’s global climate conference in Egypt.

TVA is planning for a nearly 1.5-gigawatt combined-cycle combustion turbine natural gas plant, which would be built on its roughly 2,400-acre reservation in Stewart County.

When methane is burned, it produces water and carbon dioxide. TVA’s Allen Fossil Plant, a natural gas plant in Memphis, emitted over 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2020 — or the equivalent of about 300,000 cars driven for a year.

TVA says the planned gas plant will cost $1.8 billion less than a solar-plus-storage project. This estimate represents the difference in “total system” cost, which includes capital, fixed, variable and fuel costs plus pipeline and transmission upgrade costs over a 20-year timeframe.

Many costs left out

But that figure excludes several other costs, including the estimated $12.1 billion social cost of climate pollution from the proposed gas plant.

TVA has not provided a breakdown of the project costs or the system costs for each option. It just has given the difference between the two system costs — in other words, the various costs associated with integrating each new power source onto TVA’s grid. Solar would require new transmission lines, for example, while the gas plant will need a new pipeline.

In fiscal year 2022, TVA had total operating revenues of about $12.5 billion. If nothing changed over the next 20 years, the difference between gas and solar — the $1.8 billion figure TVA provided — would represent a 0.7% change in overall system costs.

TVA excludes some key data to understand its calculations, such as the predicted power needs for the valley and fuel costs. After the draft environmental review this summer, the Environmental Protection Agency told TVA to “transparently disclose” modeling methodologies and assumptions and modify its proposed action or pick a different option “because of the urgency of the climate crisis.”

Courtesy Anders J/Unsplash

Courtesy Anders J/Unsplash TVA plans to add 10 gigawatts of solar to its system by 2035.

An executive order by President Biden requires the federal government to achieve a carbon-pollution free electricity sector by 2035. To meet this deadline, TVA would either have to close the proposed gas plant early or build hydrogen or carbon capture and storage facilities. These expenses were not included in the cost, and TVA did not commit to either of the mitigation technologies.

“Costs associated with hydrogen, carbon capture and storage were not provided because they are not known and evolving as the technology matures,” TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said in a statement to WPLN.

Carbon capture technology received billions of dollars of subsides in the Inflation Reduction Act, but the efficacy of this technology, which was backed by major oil company lobbyists, has not been established. Hydrogen is clean when paired with renewable energy, but experts warn that no hydrogen produced from natural gas will ever truly be climate-friendly because of methane leaks from drilling and pipelines.

EPA recommended these mitigation measures to TVA and said TVA should consider their costs.

“Multi-decade time horizons associated with new or refurbished fossil fuel (electric generating units) present financial risks to TVA and its ratepayers,” EPA wrote in June. “Wind and solar are currently cost-competitive despite minimal subsidies and offer future opportunities for cost savings compared to coal and natural gas.”

EPA has not released additional comments since the release of the final environmental review. The agency says it will share any new comments with the public after the review period.

The other cost consideration omitted is the potential for savings from the Inflation Reduction Act. TVA says the law could improve renewable and storage pricing, but adds the “effect of that legislation on these markets is unknown at this time.”

‘Every utility should be ripping up their plans’

Leah Stokes, a University of California, Santa Barbara political science professor and utility expert, says the federal legislation will provide big incentives. It even specifically names TVA as an entity that can take advantage of new wind and solar tax credits.

“Every utility across the country in the wake of this legislation should be ripping up their plans and starting to build wind and solar themselves, because it’s going to be a lot easier for them to build,” Stokes says.

Utilities like TVA have historically been able to make more money by building fossil fuel plants, rather than working with third-party developers on wind or solar projects, says Stokes. She points to the annual financial disclosure, called a 10-K filing, TVA provides to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

“That can lead to more profits and allow executives or board members to maybe be compensated at a higher level,” Stokes said. “Traditionally, wind and solar are built by other companies and it’s not as easy for utilities to profit off of them, or for executives to make money by building wind and solar.”

TVA refutes this claim.

“In no way are there metrics that favor one generation option over another, but rather that all of our operations are operated safely and effectively,” TVA’s Scott Brooks said in a statement.

TVA provided a calculation on the social costs of greenhouse gases from each power option, showing gas will cost billions more than solar — $10.5 billion more over 20 years by one of its own estimates. In the same document, TVA said that the climate impacts of gas and solar are “relatively close.”

What is possible?

In a dozen years, U.S. electricity could be transformed into 100% clean energy, according to the National Renewable Energy Lab, which is part of the Department of Energy.

There are a lot of different pathways to achieve this feat. The one with the most net benefit uses all clean energy technologies, like renewables, nuclear and hydrogen — and no fossil fuels.

Wind and solar could make up 80% of the nation’s electricity, and possibly even more, according to energy analyst Trieu Mai.

“Every time we keep looking, we can’t find that point where we couldn’t deploy more,” Mai says. “So right now, the point where we’re examining is, can we get above this 80 or 90% level?”

In other words, TVA has many options to change its power mix.

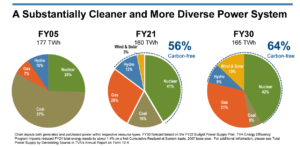

In 2021, TVA had just 3% wind and solar. A little over half was nuclear and hydro, 1% was energy efficiency, and 44% came from fossil fuels.

Two months ago, TVA leadership suggested they want 20 new nuclear reactors, in the form of small modular reactors, in Tennessee. TVA also has plans to add 10 gigawatts of solar and 5 gigawatts of storage by 2035.

TVA is promising solutions in the future.

But, right now, TVA wants to build a new fossil fuel plant to replace a legacy fossil fuel, coal. The TVA Board voted recently to give the power to make the final decision on the plant solely to its CEO, Jeff Lyash. He declined WPLN’s request for an interview until after they finalize their plans.

That decision could be made as early as Jan. 2.