An advertisement in opposition to Nashville’s transit plan has been retracted for including a faulty number.

The inaccurate information appeared in a newspaper and flyers, and was questioned by WPLN during what has been an increasingly combative debate by the groups that have lined up for and against the city’s mass transit proposal.

Before early voting begins April 11, the factions have ramped up their messaging, including attempts to sway voters through warring mathematics.

Print Ad Changes By Billions

The recently retracted ad was created by the anti-transit No Tax For Tracks organization and appeared in The Tennessee Tribune, in flyers, and on the group’s website,

where it remains unchanged (second link down).

The ad claims that the proposed light rail corridors are “where 90% of the $9 billion will be spent,” a figure that doesn’t pass muster. Metro’s

55-page transit proposal spells out the light rail corridor costs as 61 percent of the spending (page 50).

A senior advisor to the group, jeff obafemi carr, said the number was an error that has been corrected, and he personally took the blame, saying that it published before he proofed it, with one key digit wrong.

“That was supposed to be a 7, it was a 9, so it slipped through,” he told WPLN, referring to the 90 in place of 70.

He said the group believes that light rail accounts for at least 70 percent of the spending — a number still higher than Metro’s calculation.

“It’s still kind of a maddening number,” carr said, “and an awesome number, when you think of 70 percent of a plan going to light rail that is old technology that doesn’t benefit the rest of the city.”

He initially provided a written justification that showed how the light rail corridors account for 81 percent of the $5.4 billion capital costs — a different kind of comparison that would shift away from the group’s originally advertised “90% of $9 billion” figure by more than $3 billion.

No Tax For Tracks now stands by its “70% of $9 billion” calculation, which appears in the newest issue of The Tennessee Tribune.

The newspaper’s editor, Rosetta Miller-Perry, said the original ad was not checked for accuracy and that the new version came out on Thursday.

“We don’t challenge people,” she said. “I’m sure they didn’t do it deliberately, I hope.”

TV Ad Escalates Disagreement

The print ad isn’t even drawing the most attention this week.

No Tax For Tracks has a related TV spot in heavy rotation titled “Facts” that includes a cost calculation in direct opposition to a number being pushed by Transit For Nashville.

At the heart of this mathematics brouhaha are two radically different estimates for how much the average person would pay in additional sales tax, if the referendum is approved.

The dispute is classic apples-versus-oranges.

Those in favor of transit report a low cost by breaking it down per month and per person — saying that the tax increase would be $5 per month. The opponents arrive at a far more impressive number by adding up the 50-year cumulative cost per household — an increase of $43,608.

Even if accounting for their different variables, there would still be a wide gap.

The crux of the disagreement largely boils down to this: the groups have competing estimates as to how many people from outside of Davidson County — visitors, tourists, and commuters — would be paying sales tax into the plan and lightening the load for residents.

(The pro-referendum side relies on a calculation by the Nashville Area Chamber Of Commerce, which is posted

here, along with three related explanations:

one,

two,

three. No Tax For Tracks has its methodology online

here.)

“There are pitfalls in each [methodology],” says Dylan Grundman, a senior policy analyst with the

Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

“It’s hard to do this sort of estimate at the local level with a great deal of precision, due to a lack of good local-level data in some cases, and particularly when combining that with the issue of taxes paid by non-residents and taxes by businesses that are then passed on to customers.”

Grundman reviewed the calculations but declined to take a side. He said the crucial percentage of out-of-county tax contributors is probably “between 20 percent and 47 percent.” In other words, somewhere between what the two sides are arguing.

But there is another way.

To avoid needing the large-scale estimates that the groups are relying on, Grundman says it could be just as helpful for residents to look on a micro level, at their own spending.

To do this, add up a month’s worth of spending on items subject to sales tax — mostly retail and food and

some services — and multiply that total by .005. That would approximate your monthly sales tax increase for the first four years under the proposal. The amount would double after that.

In the spirit of fact-checking, and after conversation with ITEP, WPLN is also correcting a figure that appeared in

a recent sales tax report. That estimate of a household’s potential cost increase relied too heavily on an ITEP number that includes other factors beyond sales tax, and was likely too high.

Instead, WPLN ran the above calculation using the federal Consumer Expenditure Survey and Nashville’s median income, to find a monthly household sales tax increase of just more than $7 for the first four years, and $14 after that, if the referendum were to pass.

Grundman notes that this method has its own shortcomings — as it leaves out inflation, as well as the likely price increases that businesses would pass on to consumers because of their tax increases.

Separate from sales tax, the transit referendum also proposes increases to the hotel tax, rental car tax and local business tax.

‘Facts’ Or ‘Lies’

The competing calculations remain one prong of ongoing disputes, largely playing out on social media.

The recent No Tax For Tracks ad on TV also prompted a response from Transit For Nashville, which charges that the 1-minute spot includes “lies.”

Mayor David Briley, an unabashed supporter of the transit plan, also took issue with the ad.

“I’m concerned that that’s not a Nashville kind of ad, that it is kind of harsh, and I’m not sure all of the facts in there are accurate,” he told WPLN.

Yet in an interview, the group stood by its TV ad assertions.

For example, the ad refers to senior citizens and states, “the plan does nothing to help them where they live or go.”

That’s in contrast to Metro’s 55-page plan, which allots millions of dollars toward free fares for elderly and impoverished passengers, as well as an expansion of AccessRide, which is the Metro Transit Authority’s on-demand bus service for disabled and elderly passengers who cannot walk to transit stops.

No Tax For Tracks’s carr, who does not use capital letters in his name, said the statement in the ad must be considered as part of the overall theme of the commercial.

“Relatively, this plan does nothing for seniors because it does not alleviate congestion in their neighborhoods,” he said.

The two sides are also warring over the ad’s claim that “not one cent of the proposed $9 billion will go to improve highways or traffic lanes.”

Metro’s written proposal allocates funds for:

- overhauling the streets and traffic signals along more than 38 miles of proposed light rail lines

- street widenings and repavings on some rapid bus lines

- fixing, replacing or newly constructing more than 20 bridges

“There’s no road improvement, there’s no fixing of potholes, there’s no widening of the streets, there’s no fixing of bridges and overpasses,” carr reiterated to WPLN.

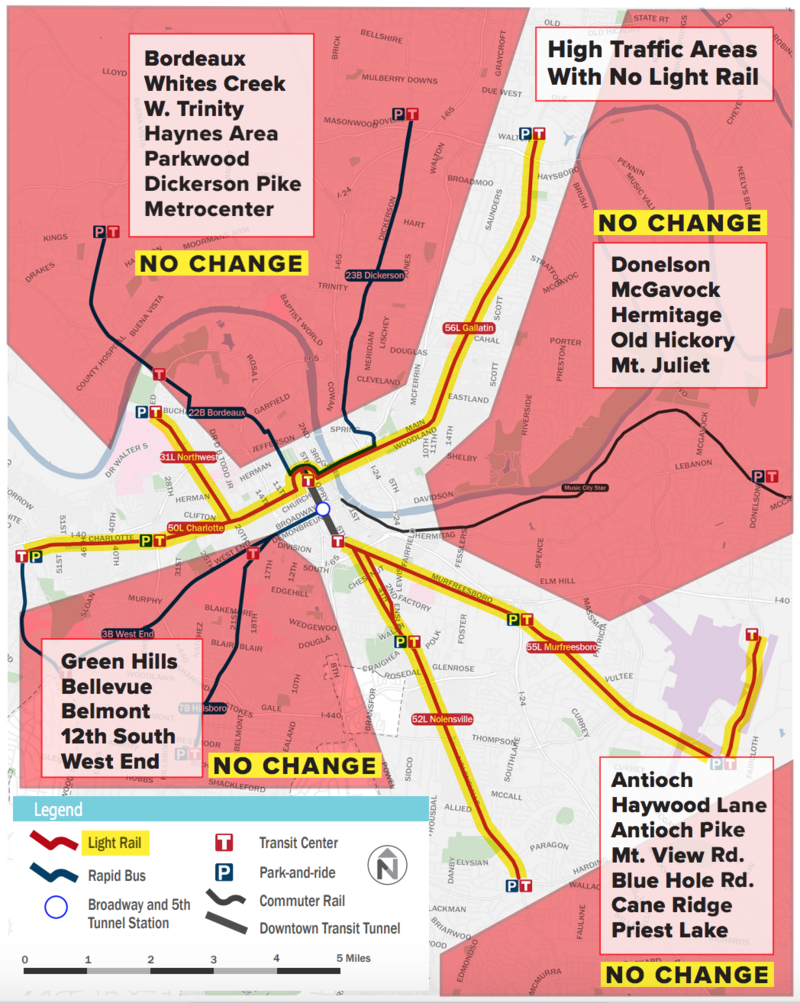

A map distributed by No Tax For Tracks underpins much of the group’s message, appearing in print, online and on TV.

The map shades large swaths of Davidson County with a “NO CHANGE” label, including over areas where the Metro plan proposes new rapid bus service, crosstown bus routes, neighborhood transit centers and park-and-ride lots.

“The concept of ‘no change’ on those maps are the areas where there’s no significant change coming in the alleviation of traffic congestion,” carr said. “The thematic element that ties all this together is fixing traffic congestion.”