It’s not even 7 a.m., and Chris Agee is already at it.

“I left at 2:30 this morning,” he says. “Anything you’re excited about, you’re willing to do about anything for.”

Including taking the day off work to stand for hours in light rain as the remnants of Hurricane Ida pass overhead.

He’s here at the Pickwick Reservoir, on the Tennessee River, about two hours east of Memphis. It’s a popular boating destination, but among birdwatchers, it’s known as the place to be after a hurricane blows through the region.

“It’s an exciting thing when something rare flies by and everyone starts calling it out and your heart starts pumping,” says Agee, who runs a landscaping business near Lebanon.

By rare, he means coastal and oceanic birds that don’t belong in landlocked Tennessee. Winds from storms like Ida, which pummeled Louisiana on Sunday, drive them inland—sometimes hundreds of miles.

It’s a tough journey, says Victor Stoll, a veteran birder from Middle Tennessee.

“They’re tired. They’re worn out. They’re just pushing ahead of it,” he says. “They don’t really have any control of where they’re going. They’re just trying to stay alive.”

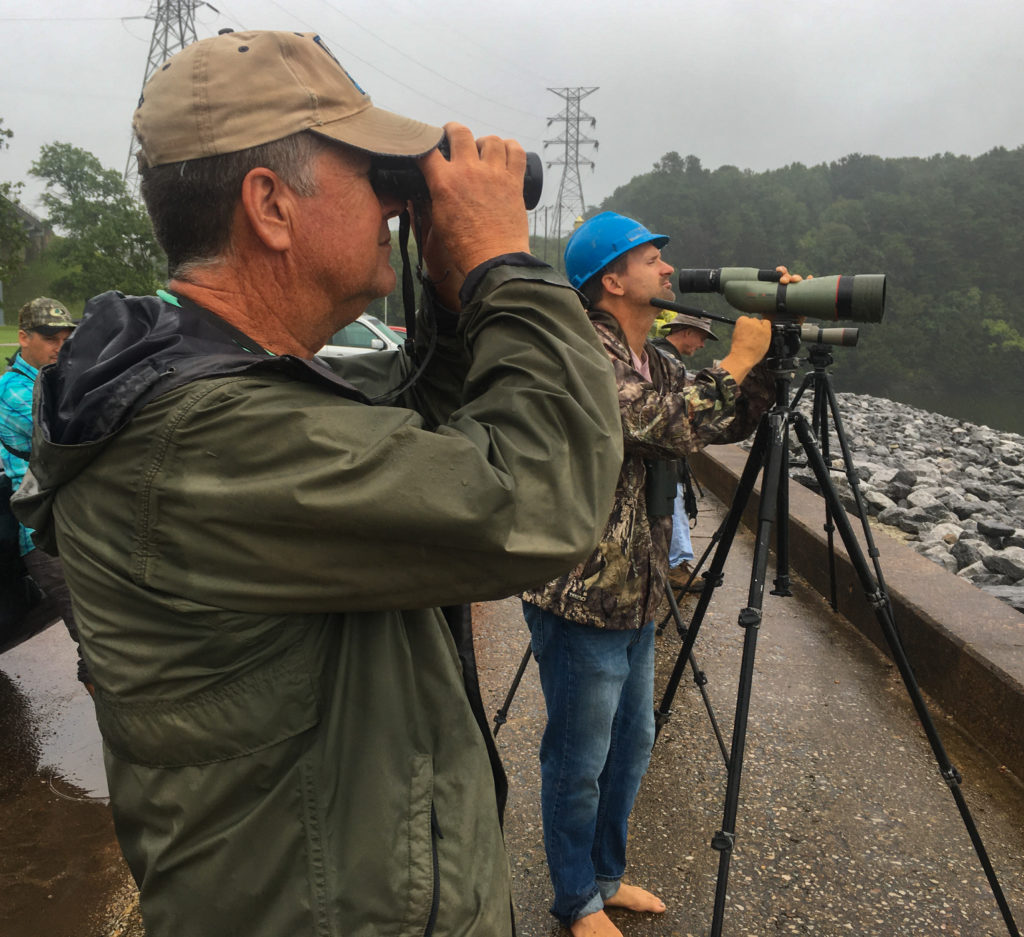

When the winds release their grip on the birds, they’ll gravitate to a body of water—like Pickwick. So the birders have to be ready with their binoculars and spotting scopes.

“You got to check pretty much everything that’s strong enough to fly by, just in case,” says Andrew Lydeard, who at 32 is one of the youngest among the small group gathered by the lake’s edge.

Lydeard points to a Spotted Sandpiper skimming the water.

“Can you see how it’s doing the flap, flap, glide. Flap, flap, glide,” he says.

But the tail-bobbing shorebird is not one of the avian outsiders he’s searching for. It’s common in Tennessee.

This scavenger hunt takes commitment and the right optics. Conditions are foggy, and the birds are unpredictable and often at a great distance. Nobody wants to be wrong about an identification.

“Sometimes, actually, that means staying on a bird for literal hours,” Lydeard says.

These are die-hard hobbyists coming from all over the state. Lydeard drove from Kentucky—twice in two days—hoping to strike gold.

“I got like three changes of clothes in the car, I got multiple meals,” he says with a chuckle. “I could stay here if I needed to indefinitely.”

Or just until the birds leave. When the weather clears, they’ll try to fly back to the Gulf of Mexico. Stoll says some won’t have the stamina for the trek.

“We always wish we could save them,” he says. “But we can’t catch them and take them back to the ocean.”

Eventually, the group joins Mark Greene and a few others, who are keeping an eye on another section of the reservoir near the dam. While Greene enjoys the opportunity for rare sightings, the excitement is tempered by the devastation these storms cause for humans. It’s a sentiment shared among the group.

“You really feel for those kinds of folks,” he says. “And realize that we’re kind of getting a benefit for something they’re suffering for.”

The reminder keeps today’s enthusiasm in perspective.

And then, word spreads of something in the distance.

Victor Stoll has it in his binoculars.

“At the height of the top of the trees…Between the towers…” he shouts.

The black-and-white tropical seabird is called a Sooty Tern—definitely rare. For some, the long-winged flier is an addition to what’s known as their “life list,” meaning the first time they’ve ever seen it.

“I haven’t had the opportunity to go out on open water, on a boat…so to get a pelagic bird and not go out on a boat is a treat,” says Rob Harbin from Collierville, using a technical term for oceanic.

For others, who’ve experienced them before, it’s still thrilling to watch them so far from their natural habitats.

Michael Todd has been hurricane birding for decades because like a magic eight ball, a storm keeps you guessing.

“We’ve had some just crazy birds show up that there’s really no explanation for,” he says. “You never know what to expect.”

It’s what bird watching is all about, says Greene.

“You got to be pretty hardcore to want to come out here and just take a chance on that you might not see anything out of the ordinary, and stand out in the rain and the wind,” he says. “But, if you’re not here, you definitely won’t see it.”

So they stay all afternoon. They’re rewarded with what they eventually I.D. as a Long-tailed Jaeger—another bird far from home, but angling south to finally put the storm behind it.

9(mda2nzqwotg1mdeyotc4nzi2mzjmnmzlza001))