An outbreak of hepatitis A that began in Nashville a year ago seems to be slowing. But more cases of the serious liver disease are being confirmed in the surrounding counties.

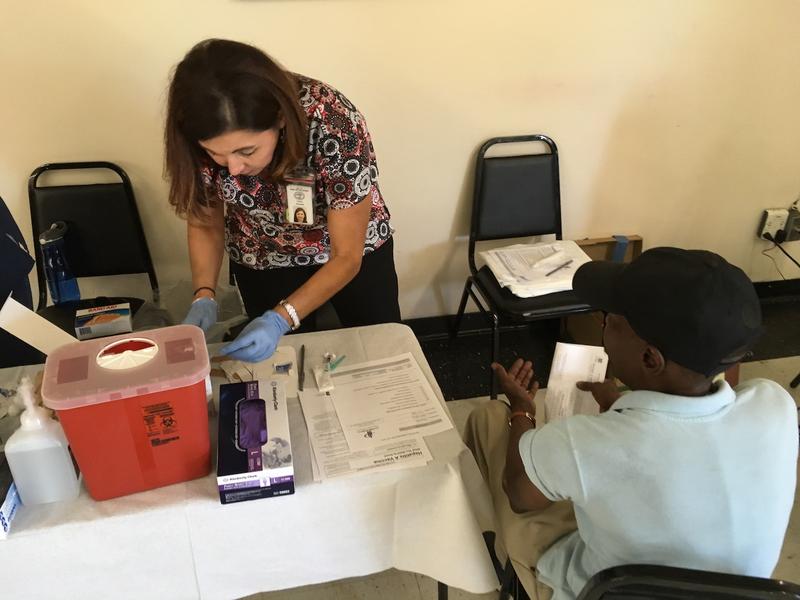

Hepatitis A infections emerged slowly in Nashville among those most at risk — primarily drug abusers and people dealing with homelessness, as well as gay men. By May, health officials

declared an outbreak and initiatied targeted vaccinations. Cases began appearing in jails,

first in Nashville and

later in Sumner County.

Then confirmed cases picked up to as many as 10 per week over the summer, with most people requiring hospitalization. In fact, state health officials typically find out about patients when they showed up to an emergency room with diarreah and nausea along with telltale symptoms like jaundice (yellowing of eyes and skin) and clay-colored stools. Many may be left with permanent liver damage.

With 156 confirmed cases and 8,700 vaccinations, new hepatitis A patients in Nashville have slowed to one or two a week.

“We are expecting a steady drip that hopefully will continue to slow down and maybe we’ll go a week without one new case,” says Rachel Franklin, who oversees communicable diseases at the Metro Health Department.

The suburbs have now become the bigger concern, tallying more than 250 cases in adjacent counties (

see the latest statewide figures here). Prevention is a bit more difficult in outlying areas since there are fewer established gathering points like homeless shelters, addiction clinics and LGBT clubs.

“They might not have those organizations that we so easily can reach out to and hopefully partner with to find these people,” Franklin says.

There’s no way to predict, but the outbreak is expected to drag on at least another year. Places like San Diego and Louisville, which had some of the earliest outbreaks in the latest hepatitis A episode,

are still confirming new cases as they enter their third year.

And officials with the Tennessee Department of Health warned after the first fatality in the state that there could be more.

“We could see more deaths, as this continues to be a very serious outbreak,” Health Commissioner John Dreyzehner

said in November. “We will continue to respond aggressively, vaccinating high risk populations, educating and working with partners in and out of Tennessee to seek additional ways to stem this outbreak.”