In a sea of new daily COVID cases, health officials are often looking for clusters — a group of cases linked to a particular time and place. But what can be even harder to figure out is how each outbreak spreads from its source and spawns even more clusters in the region.

That’s what health care reporter Brett Kelman attempted to map out as part of his investigation published last week in the Tennessean. He talked to WPLN’s Rachel Iacovone about the unexpected links he discovered.

Listen to the interview above, or read audio highlights below.

Food production and frat parties

One of the more surprising connections Kelman discovered in his reporting was between the cluster at the Tyson Foods plant in Goodlettsville, where around 280 people came down with the virus, and the so-called “St. Fratty’s Day” parties held by Vanderbilt University fraternities in mid-March.

Up until now, Kelman says, the Metro Health Department had largely worked under the assumption that the Tyson cluster was accidentally sparked by a religious retreat in southeast Nashville. Though that may still be true to an extent, Kelman found there was also a link to that Vanderbilt cluster, giving a different possible origin source for the largest and most impacting cluster in Nashville.

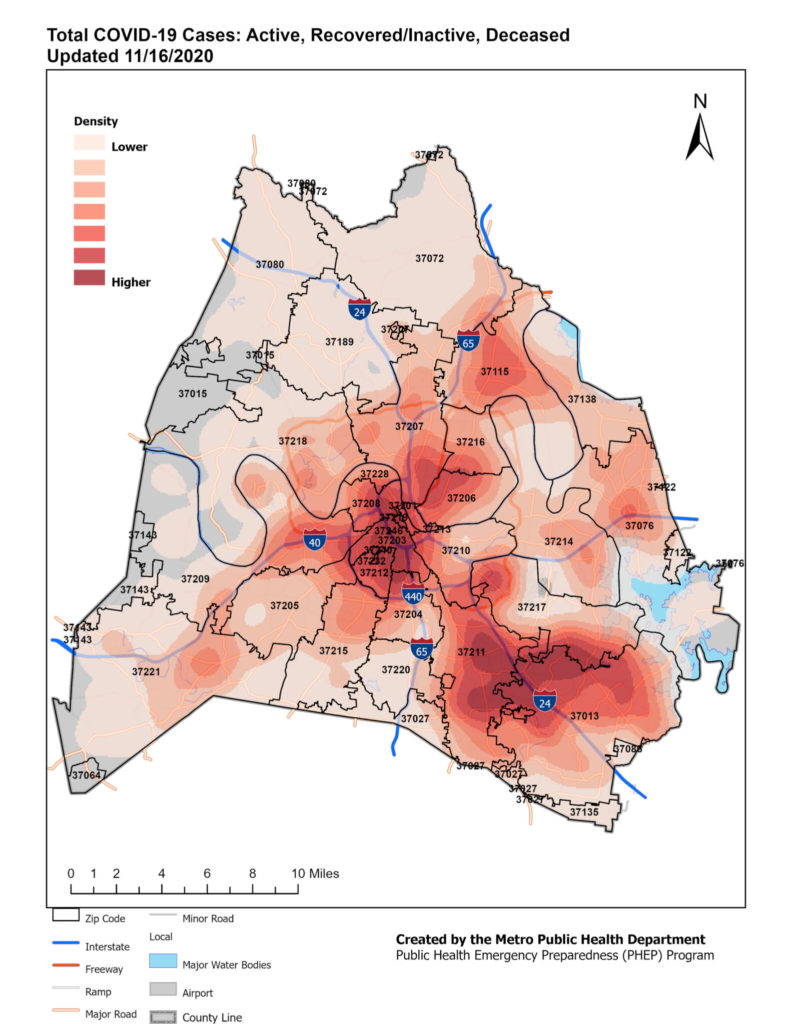

“What my investigation shows is that there were many, many likely opportunities for the infection to spread from that [Tyson] cluster to approximately 10 other known cluster sites in the city. And then, each of those cluster sites is an iceberg of its own and they have the potential to spread to other cluster sites,” Kelman says.

Inspiration from an unlikely source

Kelman’s reason for untangling this web came from an unexpected source.

“It was actually some Twitter trolls,” Kelman says.

They challenged Kelman to explain how he knew the daily statistics he reported and wouldn’t take “this is what city or state officials said” as an answer.

Kelman began pursuing contact tracing data, a tough thing to get municipalities to publicly share since it’s inherently very private. There’s a great deal of personal information included and no reason most cities would have readily redacted copies.

But that changed, thanks to Lower Broadway. When several of the large downtown honky tonks sued over Nashville’s coronavirus restrictions, the city was required to take its contact tracing data and strip that identifying information away as part of the discovery process.

“That inadvertently created the exact records I was looking for, and without that lawsuit from some of the biggest bars in the city, the data that is the basis of the story never would have existed,” Kelman says. “I sincerely doubt their intention was to create this data for the grand pursuit of in-depth journalism, but they did it anyway.”

Looking back to look ahead

The clusters Kelman highlights in his reporting happened months ago, but he says the connections are helpful even today.

“If I redid this story tomorrow focusing on the recent months, the map would look different, there would be a different web of connected clusters, but the message would still be the same,” Kelman says.

“Your behavior or my behavior can have impacts all over the city that we will never understand. If I drop my guard and do something irresponsible, I could set off a chain of events that leads to a cluster on the other side of the city that I never know is connected to me. And, that was true in March. It is true in July. It is true in November. And, it will still be true next year.”