Through the years, 2020 has come up in predictions of a world in which everything would be somehow easier. Midcentury futurists imagined we’d travel in flying cars, not get caught in downtown loop gridlock. They even predicted near-magical health devices that could stave off even the most minor cold.

Reality has clearly been different.

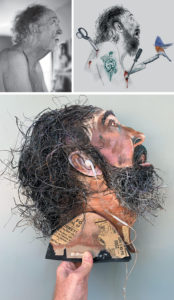

Nashville artist Wayne Brezinka has a long track record of making portraits and art for magazine covers, often summing up a lifetime or a complex idea in one, detailed image. He’s making a portrait of this year using contributions from the community, and his work suggests the more accurate picture of 2020 is centuries old: the Biblical character of Job.

Nina Cardona: For those who might not be so familiar with the Biblical story, why do you feel like Job is the metaphor for his year?

Wayne Brezinka: The character of Job, even though everything was being stripped from him, everything was falling to the wayside, he sat in dirt and ashes, with sores all over his body, and still believed, still had hope. And so I believe there still is hope in the dismal place we find ourselves in 2020. There is an end and there is a light. And so I think the character of Job, the way I see him, is a beautiful vignette.

Wayne Brezinka

Wayne Brezinka Several years ago, Brezinka’s father-in-law posed for concept photos of Job after a church sermon on the subject. This year, Brezinka pulled the photos out and began sketches and a mock-up version of what a Job collage could become.

NC: You’ve done a number of collage portraits, using objects closely related to the subject to help create the image of them. I’m thinking of the depiction of Abraham Lincoln made entirely from Civil War era artifacts, or the portraits of John Siegenthaler and Mister Rogers made from their personal possessions. You’re making Job using the same type of collage. But what are the materials that you’ll be cutting and fitting together to form the image?

WB: The materials I’ll be using for Job are submitted items from the public, photographs, stories, emails, There is a call of submission on my website. Anybody can participate. So my vision is a modern day Job, he’s got earbuds in his ears, he’ll have tattoos, and he’s sitting on a pile of trash. In that trash will be video screens with looped, submitted photographs And so those items and those pieces and those physical, tangible objects will be embedded.

NC: I understand you have a new submission on hand right now–can you open it up and see what you’ve been sent?

WB: I do, I have several here and this particular one is from a gentleman named Hal. This is interesting, he has a note and it says, “Hi Wayne, I’m glad to participate in your newest project, ‘Disrupted.’ I’ve included,” [Wayne takes an emotional intake of breath, exhales, his voice is shaky as he continues], “I have included my paternal grandmother’s thimble and thread and my grandfather’s rosary.” These are the kind of things that people are sending me. I mean, they’re entrusting me. The vision I have for this piece is to bring this work to life and to stand back from it and just let people come up on it and grieve.

Wayne Brezinka

Wayne Brezinka This rosary was sent to Brezinka by the grandson of its original owner.

NC: That’s incredibly personal, what he’s sent you and certainly the kind of things that would give him comfort remembering his family but also a rosary, something that probably would have given his grandfather hope during his own lifetime. That seems to tie right into your idea of the project and Job.

I think what I’ve learned in my own life, Nina, is that grief is not sellable, sorrow is not marketable, and that’s what this piece is about. And in order to make room for the hope and something new we must grieve, we must feel and let go.

WB: On just a practical basis, how do you then look at “how am I going to use this in this piece?”

A: I work in pieces. And so, as the work comes together, I just begin laying them you know on the wood panel or on the piece that’s in process. And right now, in my mind, I think that’s got to go around Job’s neck.

NC: So once you make this image of Job what are your plans, or at least your hopes, for showing it?

Wayne Brezinka

Wayne Brezinka Brezinka plans to make the artwork 8 feet tall. The scale is larger than anything he’s made before, but he believes the scale matches the import of the year.

WB: My big vision and really where my joy comes is being able to take this on the road in a multiple city parking lot tour. And what I envision is a clear glass box truck that this work could slide into, where people would be able to come up, you know, and engage it with a mask on in a safe, COVID safe environment. Then, I would just drive it off to another city and another parking lot. So, it would not necessarily be in a gallery or a museum. It’s more of a people’s artwork, you know, where it travels and is mobile.

NC: If you were on the other end of this, what would be your submission? What object crystalizes the experience of 2020 for you?

WB: There’s a beautiful place West of Nashville, a friend of mine’s parents own this farm, and along the tree line is this beautiful gorgeous creek. Most of the summer I have spent weekends and many hours out there, and there I have found this serenity and my own connection to my higher power again in a way that I never have experienced before. As I’ve walked I have noticed these rocks with perfect holes in the tops of them, almost as if somebody drilled through. I have collected them and some of them are small enough to string a piece of leather through of which I’ve done and I’m wearing one as we speak. [The rocks] for me symbolize serenity and trust, and “there’s something bigger out there, Wayne.” There’s something bigger than what’s happening in 2020. So I would submit one of these stones.