Songs can go extinct. Lose track of the words, or the tune by which to sing them, and the oral tradition of passing on folk songs can become a precariously thin thread through history.

But one family — even one singing amongst themselves way out in the country — can do a lot of good. In Tennessee, the Hicks family of Fentress County single-handedly preserved numerous songs that would likely have vanished.

Some of their old folk ballads will be sung on stage in Nashville on Saturday and celebrated publicly for the first time in generations.

It’s part of a one-time fundraising concert that features a wide array of traditional musicians (

event information here). The showcase includes Grammy-winners, multi-generational banjo pickers, and even internationally known guitarist Scotty Anderson (

hear more from the players here).

And there with them will be Carmen Hicks McCord, 63, who had a remarkable upbringing in East Tennessee.

She knew both hardscrabble farm life and chores — “We finally did get running water … the year I was 10 or 11” — and ample music, which was baked into everyday life by her father.

“My dad sang all the time, every day. In the mornings, I would wake up to get ready for school and help with breakfast, and I would hear him singing in the kitchen,” she said.

This man with all the words to hundreds of songs was Bessford Hicks.

His family, and its trove of ballads, were discovered largely by chance in the late 1970s.

Bob Fulcher, an upstart ranger at the time at the Cumberland Trail State Park — and now a living legend in music preservation circles — realized the Hicks family knew words and tunes that had otherwise disappeared.

He’d been pointed in their direction by a friendly banjo player who didn’t even know the family’s name, only that they lived in Tinchtown, Tenn. Fulcher got lucky knocking on doors, met Dee Hicks (brother to Bessford, who by then had passed away), and soon began the urgent project of making field recordings of the family.

Fulcher says the family’s songs date back generations, to the early frontier days of the region and back across the ocean to Europe.

“For a family to have singing like the Hicks family did in the 1950s and ’60s, now that is something that did not happen in many families in North America,” Fulcher said. “I don’t know where else it ever happened.”

On a recent afternoon, Fulcher traveled to Bon Aqua, an hour west of Nashville, to hear Carmen Hicks McCord at her current home as she prepared for the coming concert.

Tuning Up The Old Tunes

When she brought up a rare lullaby, Fulcher politely asked her to sing it — and marked its significance as a piece that only the Hicks family had, anywhere in America, in its complete form.

Hicks McCord sang of a mother pig mourning the loss of a piglet and gathering her surviving family.

“She said come up my poorest poor little pigs it’s time for us to move our bed,” she sang. “It’s time to move away.”

Despite the morbid subject, it was one that her father would regularly sing before bed, while warming a quilt over the coal stove.

“And he would sing that, and then he would wrap us up in the blanket and carry us up where we didn’t have any heat, to put us to bed,” she said.

That’s how she learned to sing these unaccompanied folk ballads, through repetition and through the memorable associations of her loving and sensitive father.

“If something was bothering you, he would know it, and he might put his arm across the back of your shoulders, and sing to you then,” she said. “I think that was his way of comforting us, too.”

They did need that comfort, as well as entertainment. As a teen, Hicks McCord worked with the family’s stock animals, cooked, cared for her siblings, and also kept straight As in school.

“When I was a child, I sang to deal with stress. Plus, it took me out of the mundane and it made me feel special that my dad would ask me to,” she said. “I think music brings out my spirit. I think it’s about being a survivor, and now a thriver, because I’m very comfortable in my life. I came out of a very bad situation as a child, and it means that I found ways to cope and rise above it.”

A Preservation Patchwork

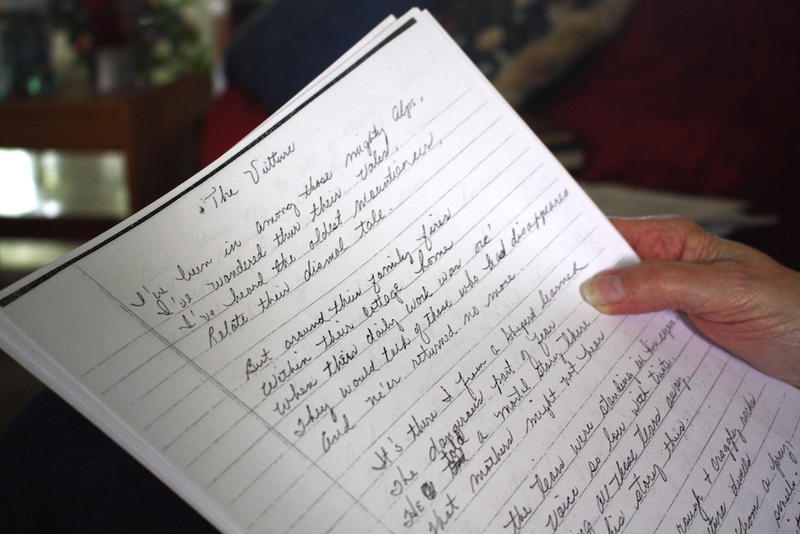

In her father’s final year, he got some of the songs down on paper.

One of them, in neat cursive, is called “The Cumberlin’ Land.” That’s also one of the few that Bessford Hicks ever recorded. While his relatives would eventually be subjects of many recordings by Fulcher, Hicks only ever recorded about 10 songs on a single cassette tape.

“I get chill bumps when I listen to it,” Hicks McCord said. “Yeah, the first time I heard it, I cried.”

This song, also to be included in the concert, was likely written in 1789 and provides an early account of explorers coming to Nashville, before it was known by that name.

When she sings it, she tells a tale of harsh weather, little role for religion and a time of tensions between migrating settlers and Native Americans.

“That song meant a lot in American history, but it vanished, except with the Hicks family,” Fulcher said. “It’s like an eyewitness account.”

He said it’s possible that it hasn’t been performed in Nashville in 200 years.

“I was not aware that it was a rarity, but now I am, and I’m really glad that we’ve got it,” said Hicks McCord.

It’s an old song that almost perished — saved by a Tennessee family that loved music, and one another.