“The Jonah People,” a new work that premieres this weekend with the Nashville Symphony, is at once a large-scale opera, oratorio, jazz symphony and storytelling experience. For trumpeter Hannibal Lokumbe, the art of composing it was a spiritual activity.

When he feels a new piece brewing, he says he goes to the forest to commune with his ancestors. Lokumbe visits his land in Texas, lights a fire as a gesture to remove his own ego from his meditation. And then he listens.

Years ago, during one of these moments of prayer — as he focused on his great grandfather’s story of forced transportation across the middle passage — he asked God a specific question: “Who do you say we are?”

The “we” being him, his family and African Americans — especially those whose ancestors were enslaved.

“We’ve been called so many names,” he recalls, saying, “and the Spirit reply was, ‘You’re like Jonah, you are.’”

In the biblical story, Jonah was a reluctant prophet who was swallowed by a whale and transported for three days and nights — something that Lokumbe understood to be a comparison to slave ships.

“You wrestled with your faith and your fate,” he heard in his meditation. “And the only difference between your ship and Jonah’s ship is that his was followed by seagulls, and yours was followed by sharks.”

The work that came out of this experience is titled “The Jonah People: A Legacy of Struggle and Triumph.”

Tenor Rodrick Dixon, who plays the roles of the Griot (a west African troubadour) and the Seer, says he found many parallels between the African American experience centuries ago and today. He cites rhythms, percussion, call-and-response and improvisation.

As an opera singer, Dixon capably handles many western European stage roles, but in “The Jonah People,” he gets to do something that feels well matched to him as well.

“I was allowed to tap into things in a different way,” he says. “Musically, spiritually, mentally, physically.”

Well over 200 performers, including singers, a jazz quintet, African drummers and dancers, and over 30 actors, will join Lokumbe on his trumpet, to premiere the work.

Colleen Phelps WPLN News

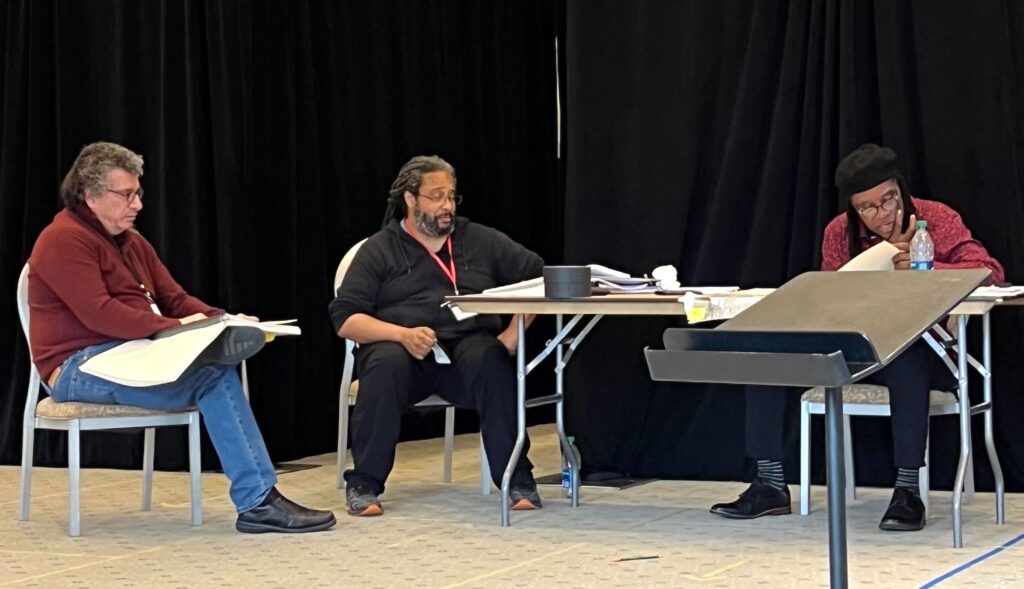

Colleen Phelps WPLN NewsFrom left to right, Giancarlo Guerrero, Jon Royal, and Hannibal Lokumbe discuss stage placement for performers.

Local director Jon Royal is assisting with the staging. He says that when the symphony first approached him they called “The Jonah People” the biggest thing they had ever done. Royal responded, “Well, surely not.” But once he got started, he found that he was amazed by the scale of the production.

As far as size goes, there are not many works that a symphony orchestra could take on that would compare in scope. Then again, there aren’t many works that cover this subject matter. And few orchestras that would be willing to take it on. So having the premiere here in his hometown was especially meaningful to Royal.

As was just having Hannibal around.

A huge jazz fan, Royal was excited to ask Hannibal about the many legendary artists with whom he’s collaborated, including Gil Evans, Roy Hanes, and many more. But he was also glad to introduce him to Nashville’s local artists.

Those meetings aren’t limited to professionals. Hannibal spent time visiting several local public schools. As a musician, Hannibal is a storyteller, and knows that if students learn to tell their own personal stories, they’ll feel seen.

“It’s a form of liberation to be able to see each other,” Hannibal says. “When we are acknowledged we feel whole as humans.”

He helped the students research their family histories as well, citing deeper connections the children formed with their grandparents as a result.

Lokumbe could write out his own history without any research at all. From one relative stolen from Liberia, to another who was forced onto The Trail of Tears, he’s constantly in touch with his family story. And all of it, down to the melody his grandmother used to hum, shapes “The Jonah People.”

“That was her example of meditating,” he says, after humming the melody. He recalls his grandparents on their front porch in the rain, with every sense awake to the sound, sight and smell of the downpour on the grass.

Other historic figures outside of Hannibal’s family also enter the stage, including Dutty Boukman, an imam who was a leader of Haiti’s first successful slave uprising. In music, he has previously written about figures like Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers and even the Charleston Nine. Hannibal has always focused on forgiveness, so it was a surprise that he included a moment of historic vengeance. But he felt it was necessary to be complete and accurate — both about the atrocities that were committed against Boukman, and about the resulting rebellion.

“Without the power of vengeance,” he says, “that revolution never would have happened.”

And Hannibal is not afraid to tell a complete story — even when it’s an uncomfortable part of history. His focus is on the truth. And “The Jonah People” is the truth about what happened to an entire people. In a time when these factual stories are being challenged within school curricula, Hannibal holds fast to the idea that students know better.

“The truth is like the wind,” he says. “You can’t contain it.”

“The Jonah People” is a journey that reaches many difficult places, but also one that ends in a full circle as Hannibal, the trumpeter, in character as himself, begins to tell his own story.

“There’s nothing you can offer me to make me not tell my story. I want (the audience) to leave with the truth. And this is not a polished version to make you feel good about,” he says. “I want you to be transformed.”

“The Jonah People” runs Thursday through Sunday at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center.

Courtesy Nashville Symphony Orchestra

Courtesy Nashville Symphony Orchestra Hannibal Lokumbe observes the set construction at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center.

—

Colleen Phelps previously interviewed Hannibal Lokumbe in 2019 when local ensemble Intersection performed his work “Crucifixion/Resurrection: Nine Souls A Traveling.” Hear about that piece and follow Hannibal to a performance at the Davidson County Correctional Facility in the Classically Speaking episode, “Hannibal Lokumbe and the Sacred Covenant of Music.”

Last week, during his interview, Lokumbe expressed his admiration for protesting students. He recalled a long-ago conversation he had with Rosa Parks.

When asked about his usual focus on forgiveness he shared the origin of his deeply-held philosophy that the act is a path to freedom. It started when he was the victim of a racially motivated attack at age 13, while he was practicing the jazz standard “Tenderly.”