The James Webb Space Telescope launched into space about one year ago. Six months after becoming fully operational, it has glimpsed distant galaxies while peeling back our cosmic history closer to the Big Bang than ever before.

The telescope sees the universe in light that has been stretched into infrared wavelengths, which might help unravel when the first stars formed, the origins of black holes and how planets get their water.

It also might help us discover life.

“The quest to understand whether our planetary home is unique or whether there are other worlds out there that are habitable like ours is one of the most exciting scientific endeavors that human beings are pursuing right now,” said Keivan Stassun, a Vanderbilt University astronomer part of the scientific team studying exoplanet atmospheres with the Webb telescope.

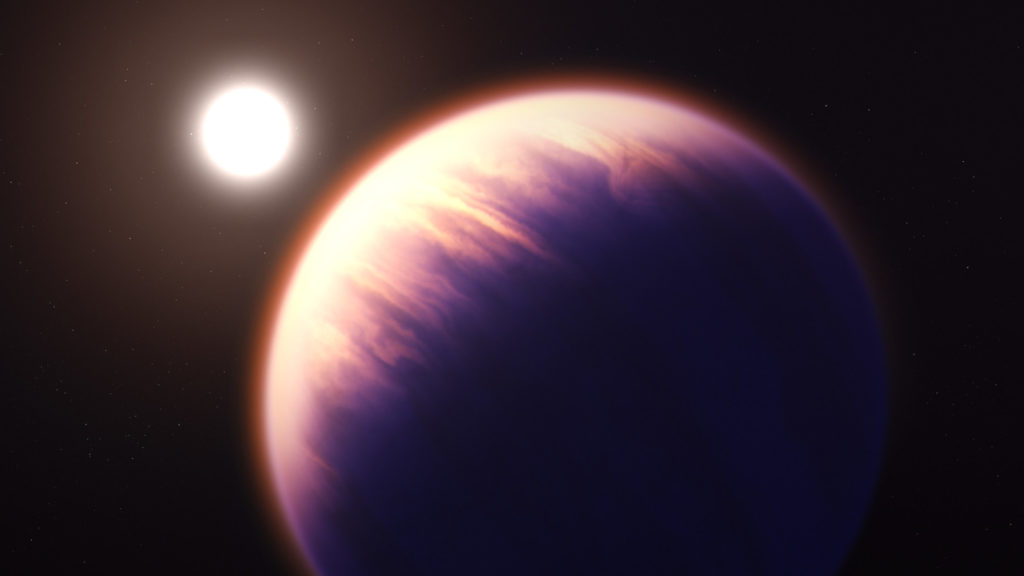

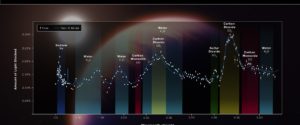

His team’s first study, published earlier this year in Nature, confirmed the presence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of WASP-39b, a gas giant planet about 700 light-years from Earth.

The astronomers have since decoded the planetary atmosphere in greater detail, recently discovering the presence of sulfur dioxide. Like with carbon dioxide, this was the first clear evidence of the chemical compound in an exoplanet atmosphere.

Sulfur dioxide is created when hydrogen sulfide interacts with ultraviolet light and hydrogen atoms — a familiar photochemistry, or reaction initiated by starlight, that reflects what scientists have observed in our solar system.

Courtesy NASA

Courtesy NASA The James Webb Space Telescope revealed the atmospheric composition of WASP-39b, a distant exoplanet whose atmosphere hosts photochemistry common in our solar system.

The researchers have also confirmed the presence of water vapor and have a strong indication that the planet has clouds, a feat Stassun compared to looking at water vapor on the back of a firefly swarming a spotlight in Los Angeles from Nashville.

“We’re looking for these incredibly faint, detailed signals of steam around a tiny thing orbiting a distant bright star,” Stassun said. “The only way that we can pull it off is to have the sensitivity and resolution and precision of this incredible space observatory.”

His team will next be looking at a planet expected to be more Earth-like.

It may be harder for the Webb telescope to detect the chemical signatures needed to understand the planet, but Stassun is enthusiastic about the prospect and its greater relevance.

This research, after all, will lead to another grand inquiry.

“Of those other worlds that are out there, how many of them, if any, actually harbor life?” Stassun said. “That’s what we’re working toward.”