Wetlands across Tennessee may soon be open for construction.

The state Senate passed a developer-sponsored bill on Monday to remove legal protections for certain types of wetlands, the saturated ecosystems in between land and water. The full House will take up the vote on Monday.

Wetlands are limited real estate, surrounding and interacting with our rivers, creeks and aquifers, near where most people live. Water covers about 2% of Tennessee’s land, while wetlands cover 7%, according to the latest state estimate.

“They are important to all of us, because we all rely on water,” said Justin Murdock, an ecology professor at Tennessee Tech who studies wetlands.

The bill targets isolated wetlands, a misnomer for wetlands that connect to waterways underground or during rainfall events. These wetlands cover as little as 1.2% of Tennessee land, but they provide big benefits by helping reduce floods and water pollution. They are even better at protecting downstream lakes or rivers from pollution than connected wetlands.

The original bill would have removed construction regulations on all isolated wetlands, to mirror a Supreme Court decision that ended federal protections two years ago. In its current form, the bill will affect about half of Tennessee’s isolated wetland acres — or possibly more.

“The original bill…is what I really think we should be doing today,” Rep. Kevin Vaughan, R-Collierville, the primary sponsor of the bill and a developer, said during a hearing earlier this month. “I view this bill as a starting place.”

The amended bill may still have, effectively, a similar result. In terms of the wetlands likely to be present in common development scenarios, the state will lose most of its protections.

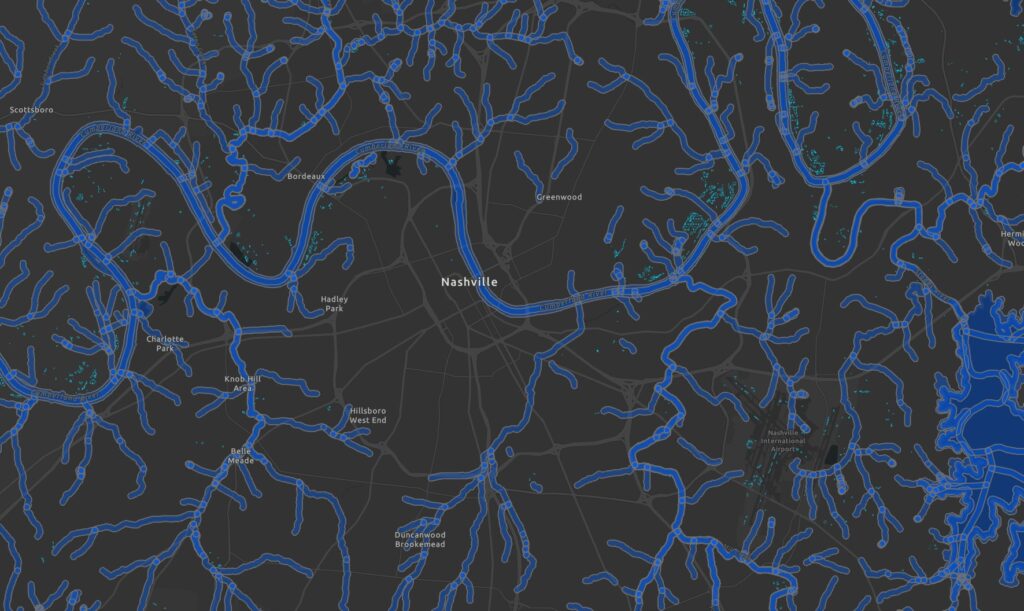

Where are wetlands in Tennessee?

Wetlands are scattered across the state near bodies of water. In the densest, developed areas, like Nashville, there are fewer wetlands. The city’s isolated wetlands are largely located at Shelby Bottoms Park, the undeveloped areas at the airport, and along parts of the Cumberland River, especially near Bells Bend, and near Tennessee State University.

But the rural areas surrounding Nashville are covered in isolated wetlands.

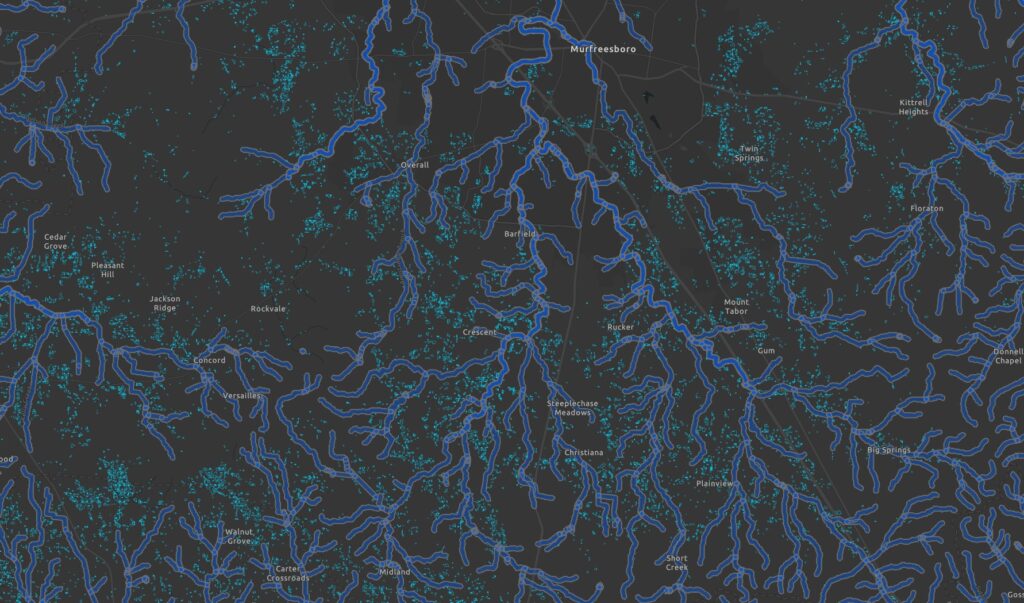

One wetland hotspot is the upper portion of the Duck River, shown above, which starts south of Murfreesboro in Coffee County and flows west through six other counties in Middle Tennessee before joining the Tennessee River. The Duck River is considered the most biodiverse freshwater river in North America and was recently named one of the nation’s most endangered rivers due to unsustainable water use from increased development and industrial expansion.

“In this particular area, these wetlands are likely playing an important, disproportionate role in slowing the water flow across the landscape and keeping streams flowing more consistently…even in times of low precipitation,” Murdock said.

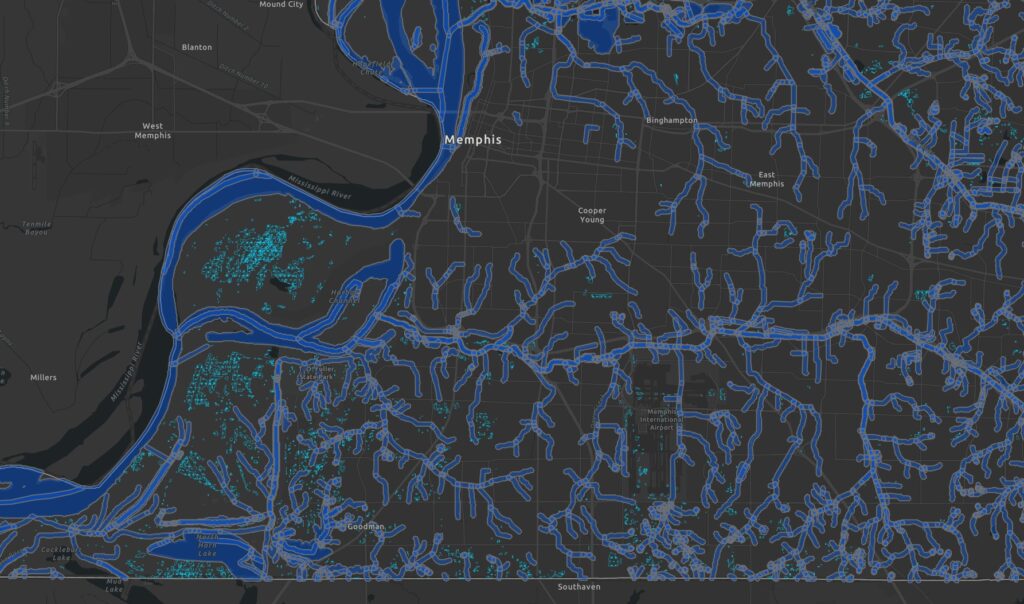

Memphis has a similar layout: The city is mostly developed, but the surrounding areas are full of isolated wetlands. West Tennessee holds the Memphis Sand Aquifer, which is part of a deep underground water source that spans 7,000 square miles and provides drinking water to more than a million Tennesseans. Wetlands in this area purify water before it percolates through soil and refills the aquifer.

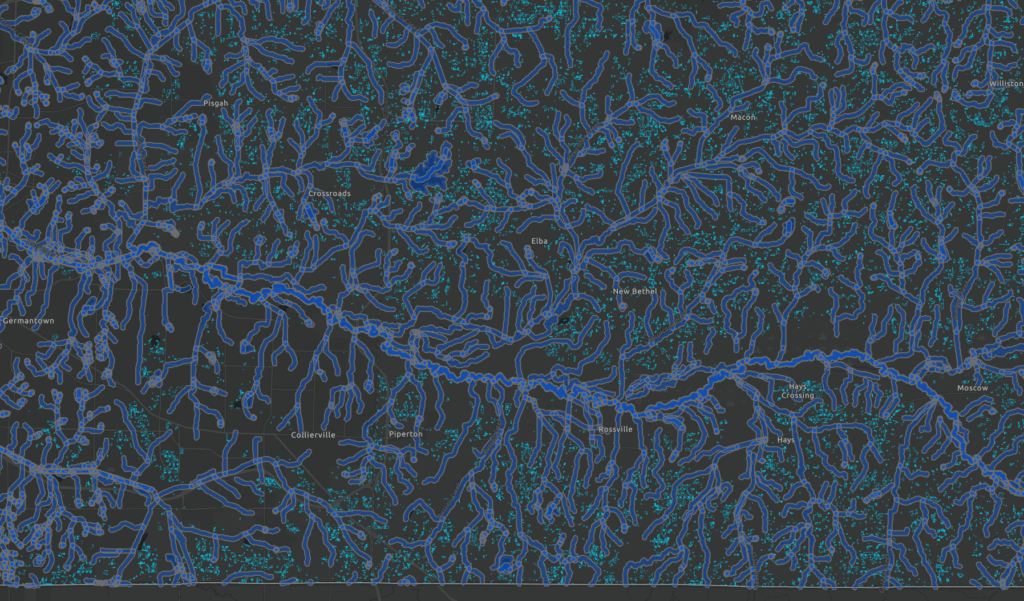

Vaughan’s district, just east of Memphis and shown in the second image below, is encircled by isolated wetlands.

If the bill passes, developers will be able to build faster, cheaper, and without the financial incentive to build around wetlands, potentially leading to serious consequences.

Developers will face little accountability

Across Tennessee, there are roughly 460,000 distinct, isolated wetlands, most being quite small. The bill lessens regulations for isolated wetlands as large as two acres and removes regulations on ones less than an acre representing 94% and 80% of the state’s individual isolated wetlands, respectively.

But an even greater percentage of wetlands may be affected: the bill allows the destruction of “an artificial isolated wetland of any size” without mitigation or notice to the state. So, depending on how “artificial” is interpreted, the legislation could impact more acreage.

In addition to artificial wetlands, an isolated wetland considered “low quality” that is one acre or smaller may be drained and filled without the need for “notice, approval, or compensatory mitigation,” according to the bill’s amended text, which will reduce accountability on the industry.

A developer could hire a third-party consultant to look for wetlands. If the consultant says they are “low quality” and under a certain size, the developer could proceed without any additional verification from the state. The developer would effectively be using an honor system instead of going through the process of permits and inspections in the current regulatory process. This is why, potentially, the legislation could affect as much as 80% or more of the state’s estimated isolated wetlands.

Developers will also no longer have to consider the accumulated total of wetlands on a given development project. If all of the wetlands present on a plot of land are each less than an acre, developers will not have to pay for wetland restoration elsewhere to maintain a balance of “no net loss” of wetlands — as state law currently requires.

‘They have more value than we originally thought’

Moving forward, the state might not be able to collect good data on how wetland loss is affecting the environment, as developers won’t have to divulge what they’re doing upfront.

“If the legislature wants to look at this again, they’ll have to do it in the dark,” said George Nolan, the Tennessee director of the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Wetland loss can lead to increased flooding, worse water quality and loss of biodiversity.

Miriam Kramer WPLN News

Miriam Kramer WPLN NewsWest Park in Nashville is flooded on April 3, 2025.

Flood protection is partially why wetlands are so economically valuable to humans. Tennessee researchers, including Murdock, have estimated that an acre of isolated wetland is worth as much as $50,000 dollars. Wetlands in Midwestern states may save homeowners billions of dollars each year due to their natural flood defenses, according to a recent report by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“We don’t necessarily know all of the benefits that they’re doing for us right now, and we’re constantly learning more,” Murdock said. “They have more value than we originally thought.”

Since the tiny slices of spongy soil are spread across the state and act as extensions of waterways, wetland destruction can have widespread impacts.

Tennessee’s environmental agency updates wetland estimates

Last year, when the same wetlands bill was moving through the legislature, the state was pointing to estimates of wetland prevalence from a national inventory. That data, from 1990, said Tennessee had about 780,000 wetlands, with about 430,000 acres of isolated wetlands.

The state now has new data. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation hired mapping company Skytec to develop a predictive model, using artificial intelligence, to provide a better idea of where wetlands are statewide based on LiDAR and historical data verified on the ground.

Based on this model, Tennessee has about 1.8 million acres of wetlands, including about 320,000 acres of isolated wetlands — translating to 7% and 1.2% of the state’s total land, respectively. If all of the estimated isolated wetlands were linked into a single landmass, it would represent the size of Nashville.

It is possible, however, that more of the total wetland acres near waterways could actually be isolated wetlands, according to Murdock, who described the estimate as “conservative.”