Not many people have sat face-to-face with communist dictators, the leaders of military coups and men who’ve been found guilty of war crimes. Fewer yet can say those meetings have helped defuse some of the world’s most tense standoffs.

But if anyone knows his way around high-stakes international talks, it’s Jimmy Carter.

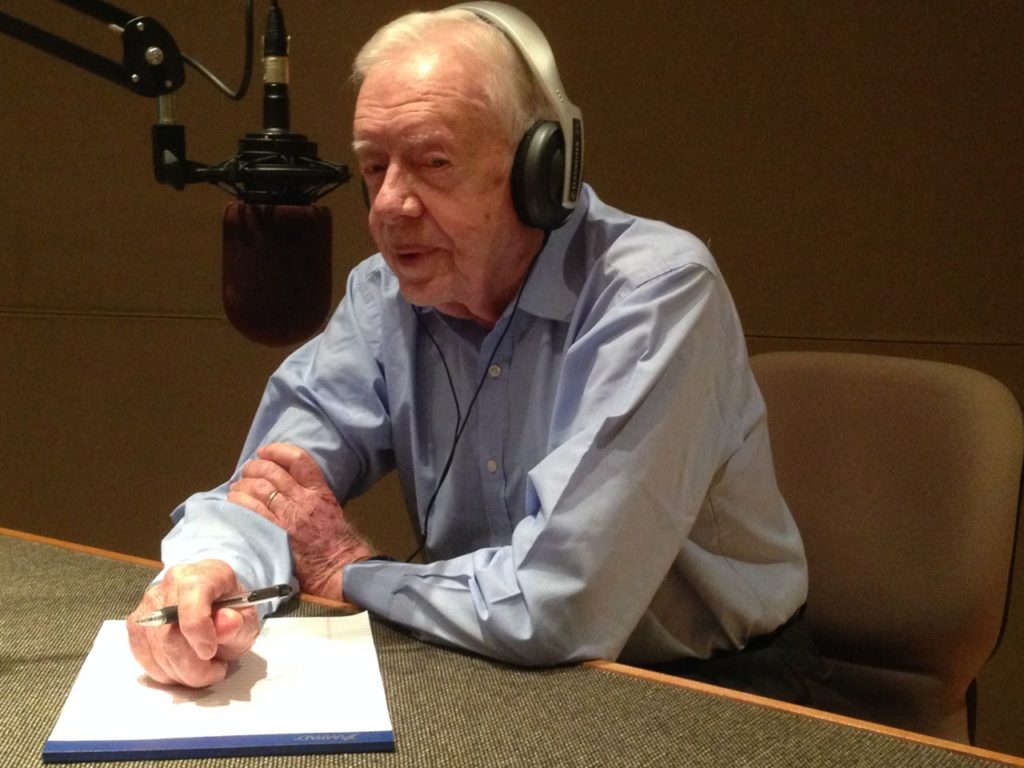

The former president was in Nashville Thursday to sign copies of his new memoir. It includes stories of how agreements that affect entire nations often come down to the individuals at a negotiating table. He says that was particularly true when he helped the leaders of Israel and Egypt hammer out a peace treaty at Camp David.

“I think the personal interrelationships were key to the whole thing. Menachem Begin was the first devout Jew that ever was prime minister of Israel. The rest of them were very secular in their attitude. [Egyptian President Anwar] Sadat was very religious, too, and I was a devout Christian. So we had three different people who were very devout religious leaders who were from different faiths. I think that was a major thing because we knew ultimately that peace was a prime characteristic of all three religions: Judaism, Islam and Christianity.”

But even so, after nearly two weeks in the forest retreat, Begin was ready to give up. “We had failed,” Carter says.

Begin asked for a parting souvenir to take home to his grandchildren: a photograph of the three leaders, signed by the American president. Carter’s secretary took the initiative to find out the children’s names, so that each could have a personal inscription.

Carter remembers walking to Begin’s cabin and being greeted with a terse, angry, “Thank you, Mr. President.”

“And he took the photographs and he turned around. He looked down at the photographs and began to read out the names of his grandchildren one at a time. When he got to about the third name, he choked up. Tears began to run down his cheek and mine, too. And he said, ‘Mr. President, why don’t we try one more time.'”

Both Begin and Sadat returned home to nations unsure about concessions they’d made, but the peace has lasted more than 35 years now. As President, Carter signed away U.S. control of the Panama Canal Zone. That treaty was profoundly unpopular with Americans and played a role in his 1980 loss to Ronald Reagan, but he did convince the Senate to ratify the agreement.

So what does he make of the current reaction to the Iranian Nuclear deal President Obama announced last week? Tennessee Republican Bob Corker, who is chair of the U.S. Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee, has said the administration should not have agreed to obligations unless Congress would agree. But Carter says that’s not a realistic approach to international talks. As he puts it, “Congress can’t negotiate a treaty.”

“It’s a very good agreement. I think if the Congress should reject the treaty it will make our country look like we’re the main obstacle to peace and we’re the ones that will bring an almost inevitable war — if Iran wants to go and build atomic weapons, which I don’t think they will by the way. So I think this is a major step forward, and I think that Sen. Corker, who’s a very fine man, is mistaken on this particular issue.”

When his committee questioned Secretary of State John Kerry on Thursday, Corker expressed his belief that lifting sanctions and allowing Iran to pursue nuclear energy would actually give the Iranians more of an ability to create weapons using the technology. Corker told Kerry he’d been “bamboozled” by Iranian negotiators.

Carter says that kind of language wouldn’t have been used in Congress 15 years ago, much less when he was President. He chalks it up to the increasing polarization of politics.

“I don’t think there’s any other senators who would agree that Kerry is the kind of man who could be bamboozled. Most of them that were there when he was a leader in the Senate know that he’s one of the wisest and most courageous people that ever have served in the Senate.” Carter says he has “complete confidence” in Kerry’s statement that sanctions will be reinstated in the event Iran violates the treaty.