Appraisals of popular output from Nashville, where convention holds sway in the shadow of the country music industry, tend to interpret a performer’s stance either as conformist or rebellious. Joy Oladokun is one Nashville contender who’s no more confined to those polarized possibilities than any other type of binary. She’s a Black, queer woman, and a child of Nigerian immigrants. An ex-evangelical worship leader, she long since moved on to the realm of pro songwriting and major label affiliation. On social media, she lists “she/they” pronouns and jokes about dressing like a dad and being called “sir” in the grocery store. In years’ worth of selfie-style diaristic dispatches, she’s espoused therapeutically knowledgeable and enthusiastically stoned insight into mental health crises.

It’s not like Oladokun is trying to be transgressive, not in the least. She learned well the principles by which congregational praise choruses and arena-friendly pop compositions alike can summon a sense of shared common ground. Sincerity is her strong inclination. She simply operates with awareness that the artists seen as speaking for the masses have historically been cishet, white men, who’ve enjoyed cultural centrality without having to acknowledge or interrogate the particulars of their own identities. Or, to put it another way, only those with the luxury of presuming the dominance of their viewpoint have gotten to be the “everyman.” And she just so happens to possess the ambition and ability to connect that broadly with her music.

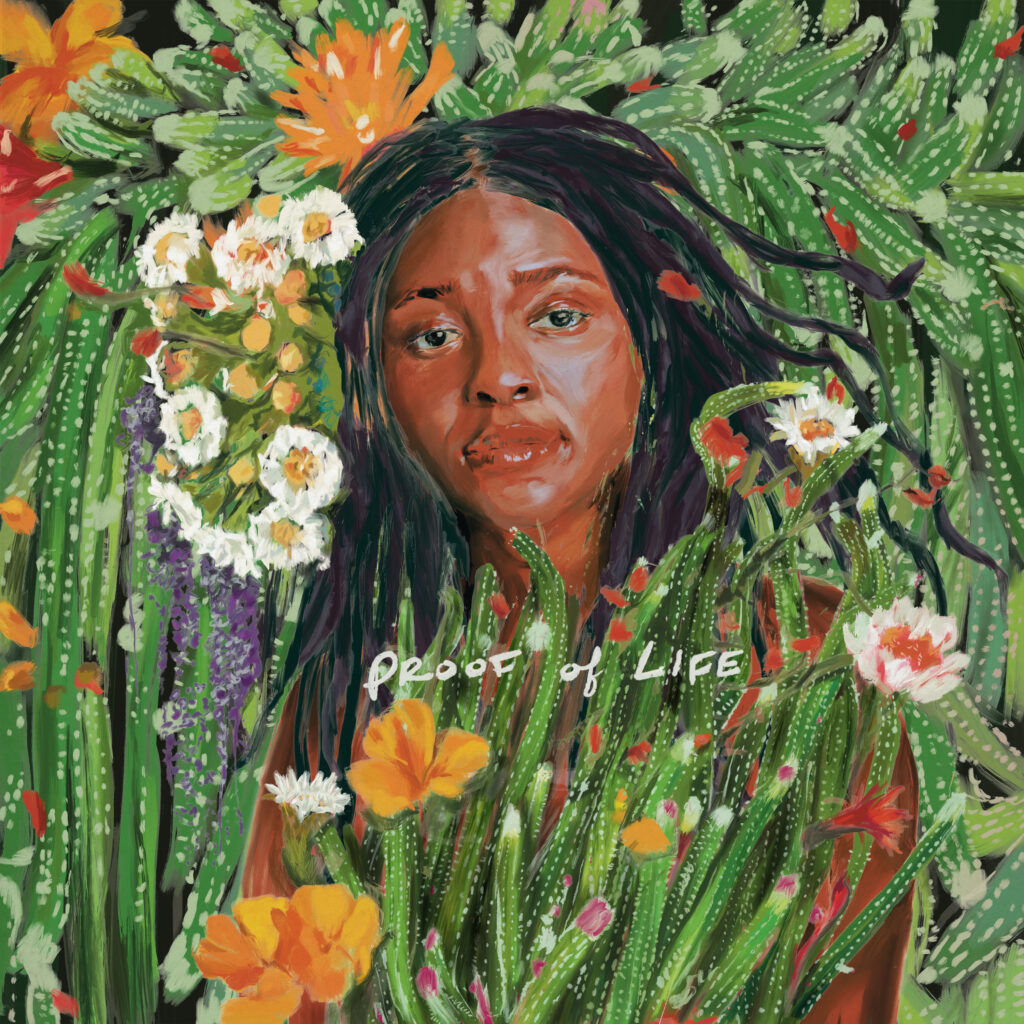

In Oladokun’s new songs, facets of who she is and what she’s lived, seen and imagined, matters politicized by other people’s prejudices, are what provide the evocative details that serve as normalizing entry points to her anthemic expression. The great theme of her newly released second album Proof of Life is what all-consuming work it is to lead an alert and searching existence, to break with oppressive orthodoxies and, in the face of the systemic devaluing of her life and the lives of other LGBTQIA+ people and Black Americans, to strain toward self-healing and put real trust in closeness and mutuality. “I pray it’s worth the heartache when I’m done,” she sings of the daily emotional labor of withstanding despair in “Keeping the Light On.”

Initially self-released, 2020’s In Defense of My Own Happiness was created in pandemic isolation; she doodled her way to emotional, relational and social verities, mainly using the instruments, microphones and software she had on hand. For Proof of Life, she entered into a partnership with Verve Forecast and Republic that didn’t break her of DIY recording habits so much as vastly expand her cast of collaborators and enable her to pursue a wider array of sonic ideas. Written and co-produced with some of the more flexible minds that operate out of or occasionally visit Nashville (Ian Fitchuk, Mike Elizondo, Alysa Vanderheym, Dan Wilson) and featuring country, alt-rock, folk-pop and hip-hop guests (Chris Stapleton, Manchester Orchestra, Mt. Joy, Noah Kahan, Maxo Kream), Oladokun ultimately arrived at a very homey version of pop maximalism.

Oladokun began “Somebody Like Me” by strumming a chord pattern into her iPhone in her backyard. That became the woolen, almost lo-fi acoustic guitar loop beneath a plea of gospelly proportions. Halfway through, the McCrary Sisters join her in mass choir-style call-and-response, underscoring the way Oladokun, while conveying anguish, also invites prayer.

A number of tracks open with personalized vignettes from as far back as elementary school. During “Taking Things For Granted,” a solo Oladokun production that gradually gathers emo intensity before taking on a Pet Sounds-esque harmonic grandeur, she summons the memory of the eighth birthday she spent alone in the swimming pool when all of her schoolmates bailed on her party. The pain of going unseen and unconsidered, she acknowledges in a refrain that seems destined for live singalongs, still lingers.

“Keeping the Light On,” whose burbling combo of lite-funk drums, Afrobeats syncopation and folkie guitars she cooked up with Elizondo and Fitchuk, begins by zooming in on the weight of her life decisions. “Found a girl and found a job, just like they say good people do,” she testifies, her phrasing subtly sinking toward melancholy. “But every now and then I turn to salt inside her wounds.” She broadens and brightens the view considerably during the chorus, the push she gives each line conveying the capaciousness of determined hope.

At the beginning of “The Hard Way,” the album’s most country-leaning track, Oladokun recounts freeing herself from the Christian culture and creeds that defined her early life with a tight couplet: “Jesus raised me / Good weed saved me.”

“I feel like nothing’s hotter right now than religious trauma and cannabis,” she jokes when we speak in the upstairs bedroom she converted into a home studio. “So I think that’s probably the most relatable lyric on there.” When she left the religious settings where she’d too often seen racism and homophobia receive a righteous varnish, she resolved to continue working out for herself what it means to live a good and spiritual life. Whether or not listeners identify with how she traded one salve for another, her insistence during the chorus that revelations don’t come easily, that she “learned the hard way,” has wistful resonance.

Oladokun doesn’t mind imperfect takes and much prefers in-the-moment feeling to flawless precision, but she’s not at all opposed to refining her abilities; she’s been taking voice lessons, in fact. Now she’ll seize on occasions that call for singing more freely and demonstratively, but that’s still tempered by her ruminative inclinations. Even when she paints a picture of a world in chaotic flux during “Changes,” the kind of stock inventory of bad news that might prompt another artist to perform as if from a soapbox, she slips down descending vocal lines with engrossed, and engrossing, worry. So present is she in her singer-songwriter pop, through those variations in inflection and tone, that her grandest gestures have powerfully modest magnetism.

Oladokun has her own standards for measuring the success of her efforts, as she lays out in our conversation: “As I continue to be a musician, the question I keep at the forefront is, ‘Is this helping build bridges or is it hurting?’ Like, ‘Am I becoming a weird corporate shill, or something like that?’ ”

A greater and more heartening possibility is that this album and the tours and exposure to come will establish her with mainstream crowds as a trustworthy voice, and one that speaks for Nashville as much as any Music Row export. “I try to contribute to the community for good,” she allows thoughtfully, “so I think it’s fair to say that I can represent the city on some front.”

by Joy Oladokun]