Wei Zhu was afraid to cut her grass.

It was March of 2021 and her yard looked bloated, like a muffin top leaning across a neighboring driveway. A walnut tree bent toward her home, where a fissure zigzagged across its foundation. Then, at the edge of her backyard — a nearly vertical, 12-foot cliff caused by a landslide.

“The first time I saw it,” Wei said, gasping, “it was shock and heartbreak.”

Last spring, a storm dropped eight inches of rain in Wei’s neighborhood in South Nashville. Overnight, a chunk of her backyard collapsed and eroded enough to make her fear if she added a little weight, the ground would crumble beneath her feet.

Next door, a lattice of limbs sat splayed across the cracked driveway of Wei’s neighbor, Althea Penix.

“There are trees falling on the left, to the right. There are trees falling forward. There are trees falling backwards. And that is a sign of a terrible erosion in the land,” Althea said.

Both women experienced a landslide last year that extended nearly 300 feet across the backyards of six homes, clearing several dozen trees on its destructive path downwards.

For months afterward, the slide crept closer to their homes. Neither Wei nor Althea could sleep when it rained. They were afraid, angry and dejected.

“We almost lost hope,” Wei said.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsWei Zhu grew sundry vegetables in her backyard before a landslide swallowed her garden beds on March 28, 2021.

Why landslide risks are increasing in Nashville

In May 2010, Nashville became a destination for landslide research after a historic, two-day rainstorm.

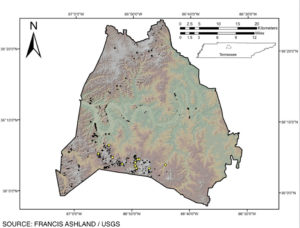

There were at least 560 landslides in the city, and probably thousands across Middle Tennessee, according to Francis Ashland, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who is studying the local erosion threat.

“It was probably Tennessee’s most costly landslide event,” Ashland said.

Courtesy Francis Ashland/USGS

Courtesy Francis Ashland/USGS The black dots represent May 2010 landslides, and the yellow dots represent some of the March 1975 landslides.

The city was unprepared. There was only one precedent for widespread landslides in March 1975, and it was poorly documented.

But now the risk is clear: climate change has increased extreme rainfall, unearthing a growing danger of landslides in Nashville.

“From a climate perspective, we have to expect that these types of things are going to be happening more often because of the change in rainfall intensity and when it’s actually occurring,” said Dr. Alisa Hass, a hazard climatologist at Middle Tennessee State University.

In the latest 30-year climate normals, Nashville has gotten wetter in every month but May and November — and many of these inches are concentrated to a few days each season.

Not every downpour results in landslides. Ashland is researching the local “critical rainfall threshold,” or the amount and duration of rain needed to trigger mass movements.

It also matters how wet the ground is when the storm strikes.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsWhen rock and soil become fractured and weathered, gravity can pull material down.

“The combination of the extreme rainfall on top of elevated moisture conditions is really the recipe for slope failures in the Nashville area,” Ashland said.

Soil moisture is largely controlled by something called evapotranspiration, the process of trees and vegetation soaking up water and releasing it into the air. During colder months, this process shuts down, allowing hillsides to easily saturate while groundwater levels climb. If there is a late freeze, like in 2021, greenery may bloom late.

Dump a massive amount of water on sloping soils that have lost their integrity, and gravity will do the dirty work.

But there is another important cause of landslides: development.

When flat ground gets crowded, developers move to the hills

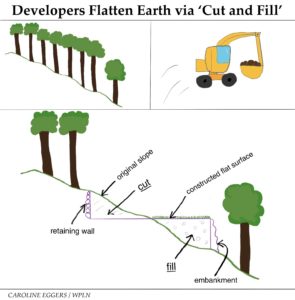

In the 1980s, developers constructed Althea and Wei’s subdivision on a hill via a “cut and fill.” They flattened the slope for roads and built up artificially smooth backyards with excavated material – and tossed in railroad planks, floorboards and tree stumps.

Decades later, the slope failed, sending a monolithic sludge toward the creek at its base.

“You can walk out here where the mud is and you’ll sink to your knee. That shows you how weak the soil is,” said Devinder Sandhu, a civil engineer in Nashville who was hired by Althea and Wei this spring to stabilize their slope.

The excavation revealed clues about the reckless development. In addition to construction scraps and organic materials, Sandhu found a street drainage pipe leaking into Wei’s yard — which opened a sinkhole in the fall.

“It wasn’t their fault that it happened,” Sandhu said, and “these guys can’t get any type of disaster relief or any kind of help at all.”

Tennessee does not map landslides

In Nashville, most landslides occur in the local patches of loose, slide-prone soil called colluvium. There have been shallow slides that scraped off small amounts of soil, and massive ones, hundreds of yards across, that displaced entire forested slopes with a few feet of movement.

Many landslides occur near recent development. But Ashland even discovered evidence of the bedrock moving among the landslides in Warner Parks, which became an outdoor laboratory since the park left the fractures untouched.

“If you hike any of those trail systems in the park, you will cross one of those 2010 landslides,” Ashland said.

Landslides can happen anywhere. Most of Earth’s surface is unstable land capable of moving downslope. In the U.S., they tend to concentrate in the wildfire-prone West and in mountainous terrain.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsDevinder Sandhu, a civil engineer, provides scale for a landslide in Nashville.

Landslide causes are also diverse. They usually involve water, from heavy rains and droughts to stream erosion and snowmelt, but they can also be triggered by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and, of course, people “mucking around with excavators.”

“There are just so many different types of landslides. It’s really a challenge to assess the hazard in a consistent and uniform way across the country,” said Ben Mirus, a geologist who helps manage the U.S. Landslides Inventory, which is a map of landslide data.

But research starts with good data — and Tennessee has not plotted many points.

The state lacks a mesonet, which would provide soil moisture data, and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation said mapping landslides is not a requirement.

“While landslides are relatively rare occurrences in Tennessee, TDEC staff are available to investigate landslide events to assist with determining the potential reasons for their occurrence when requested by the public or other government agencies. Maintaining records of individual incidents of landslides does not fall within TDEC’s regulatory authority,” TDEC said in an email.

That’s in contrast to Kentucky and North Carolina, which appear heavily dotted on the U.S. Landslides Inventory while Tennessee looks barren. But Tennessee is not special. The imaginary border between the states just highlights the difference in tracking.

“The lack of a mapped landslide doesn’t mean a landslide hasn’t happened,” Mirus said.

Nashville has not mapped its geologic hazards either. The Office of Emergency Management identified this as a priority in its Hazard Mitigation Plan, along with the recommendation to require geotechnical assessments of proposed development.

“It is recommended that the definition of a critical lot be expanded to include specific geological details and defined subjectively during plat review and that the critical lot concept be used in review of other developments,” the plan authors wrote.

In other words, Nashville developers may still be creating new risks — and the city remains largely unaware of the old ones.

This data dearth is also a problem because agencies do not know when to put out a warning or where to respond, as landslides tend to happen where they’ve already happened in a process called reactivation.

If agencies track them, the experts say, they can start to define them and be proactive, potentially saving lives and property.

“We need more people to know this stuff can happen, and there are ways to prevent it,” Sandhu said.

But action costs money — and blame could be thrown at cities and developers.

‘Now, it can rain all it wants to’

For months after the landslide, Althea and Wei sought aid. The initial cost estimate to repair the slope was $100,000, per yard, out of pocket.

City officials refused to help. Engineers feared liability. And, unlike other weather and climate events, landslides are not covered by insurance — even though the March 2021 storm earned a federal disaster declaration.

The women were frightened to stay in their homes.

“Every time rain started falling … 3 o’clock in the morning I’m standing at my window staring at the back. Did part of my driveway sink in?” Althea said. “It was hard.”

Wei left to live with family in Miami for six months after her daughter went away to college. One neighbor moved. Others struggled with the idea of leaving what they thought was their permanent home and community.

It was not until this March, a full year after the landslide, that the burden started lifting.

Sandhu accepted the job. He actually insisted on it, giving them a considerable discount.

“Because the slide was moving so close to the houses, we had to do something,” Sandhu said.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsWei Zhu and Althea Penix are standing in their backyards-in-progress on April 28, 2022.

After Sandhu’s engineering crew removed the debris, which included upwards of 40 fallen trees, they began rebuilding the slope with different gradations of rock, clay soil and top soil, with layers of a plastic geofabric in between.

The geofabric, also called a geogrid, appears like a thin black net. Sandhu likened it to snowshoes holding up humans on snow.

“It doesn’t look like much, but it’s very strong,” he said.

For two months, Althea and Wei watched their yards climb each day, becoming increasingly eager to dip their hands into soil and grow greenery. Althea wants rows of roses and neatly structured landscaping. Wei intends to sprout dates, vegetables and new trees.

They still have hardships ahead. Repairs will cost tens of thousands of dollars.

But the two women, bonded by disaster, are finally imagining the next decade in their homes.

“Now, it can rain all it wants to,” Althea said.

“At least I’m safe now,” added Wei.