Six years after he was let out of a Tennessee prison, a Wilson County man still hasn’t been officially declared innocent.

Now a state lawmaker is getting involved. He says the case illustrates how hard it is for people who’ve been wrongfully convicted to receive justice.

In the late 1970s, Lawrence McKinney was sentenced to 100 years in prison for a rape and burglary in Memphis. He spent three decades behind bars before DNA testing led authorities to conclude he didn’t commit the crime.

State Rep. Mark Pody, R-Lebanon, says that should have been the end of it.

“DNA can convict. DNA can show innocence. If we can convict on DNA, we should be able to exonerate on DNA, and let’s move forward. You can’t have double standards.”

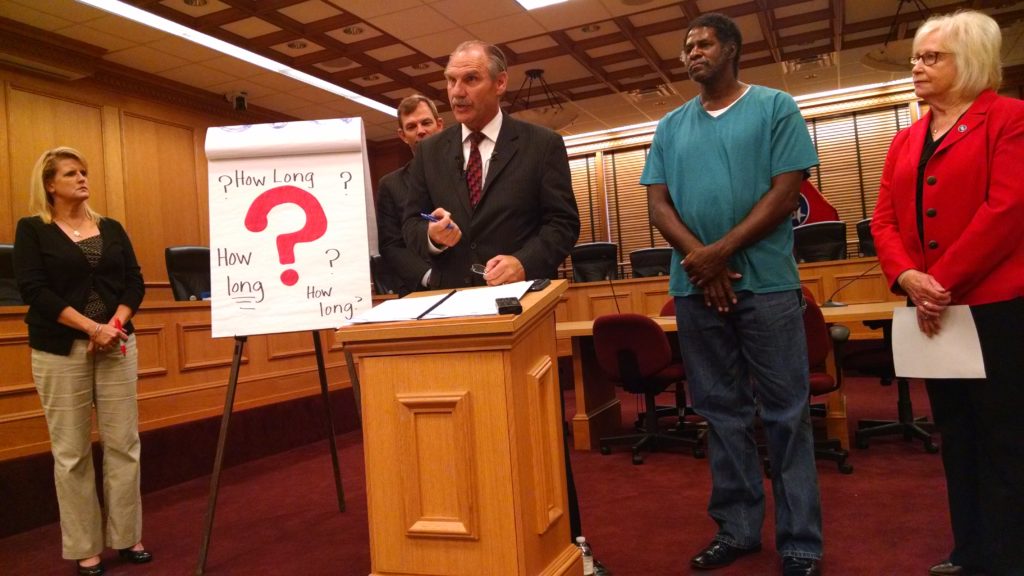

Pody called a press conference Thursday to draw attention to his case. He was joined by McKinney and state Sen. Mae Beavers, R-Mt. Juliet.

They say McKinney’s case shows that even when people are cleared based on DNA evidence, they can face a long road to redemption.

Though McKinney was released, he’s never been “exonerated” — that is, given an official decree that says he’s innocent. Without that statement, McKinney can’t receive compensation from the state’s fund for the wrongfully convicted.

Instead McKinney, who is now 60, scratches out a living through manual labor.

The case rests with the Board of Parole, which has considered his application for exoneration once before. In 2010, board members held a 90-minute hearing in which evidence from the 1977 case was reconsidered, including statements from McKinney’s supposed accomplice, the victim’s identification of him as a culprit and whether McKinney fully understood the evidence against him.

Members admitted there was no DNA evidence linking him to the crime scene. But they said that didn’t prove he didn’t take part, and they pointed to statements McKinney had made through the years suggesting he was at least present.

The Board of Parole could reconsider McKinney’s case in September, but it will just make a recommendation. Only the governor can issue a formal exoneration, and traditionally that doesn’t happen until the end of a governor’s term.

A spokeswoman for the governor would not say whether it intends to follow the same procedure for this case. She said only that “it is the administration’s policy to consider executive clemency requests after receiving a recommendation from the Board of Probation and Parole.”

Pody wants the board and the governor to expedite McKinney’s application.

He also plans to introduce legislation that would speed up exonerations for people released on DNA evidence.