The old Tennessee State Prison, also known as “The Castle,” has drawn a lot of attention this year. There’s been talk of redeveloping the largely dormant site along the Cumberland River. And with the blessing of the Tennessee Department of Corrections, a flying drone video documented the property extensively.

But it was in a different medium, back in 1933, that the prison produced some little-known musical recordings.

The genre of field recordings pivoted that year as folklore father-son duo John and Alan Lomax sought out prisons across the south.

“Folk songs are primarily an expression for people who don’t get other ways to put their thoughts out,” says Mark Jackson, an MTSU English professor who studies American folk and political music and curated a

jail songs compilation in 2012.

Jackson says prison recordings gave poor, oppressed people — and African-Americans — the chance to express harsh realities. And the listeners, then and now, can gain understanding and empathy for overlooked groups.

About the arrival at the Tennessee State Penitentiary, Jackson writes:

When Lomax arrived in 1933, the prison was still awash in human flotsam; men and women (both black and white) were packed into deteriorating cells and suffering under the administration of cash-strapped state authorities. But in this imposing structure, overfilled with those society had convicted and then shunned, Lomax found many wonderful singers who gave voice to the experiences of the black community…

Inside, the folklorists captured work songs like “Jumping Judy,” which they’d first documented only a couple days earlier at the Shelby County Workhouse.

“[Lomax] thought [Allen Prothero] had a really beautiful kind of tenor. He called it ‘bugle-like.’ So it has this kind of force to it, but also a clarity,” Jackson says.

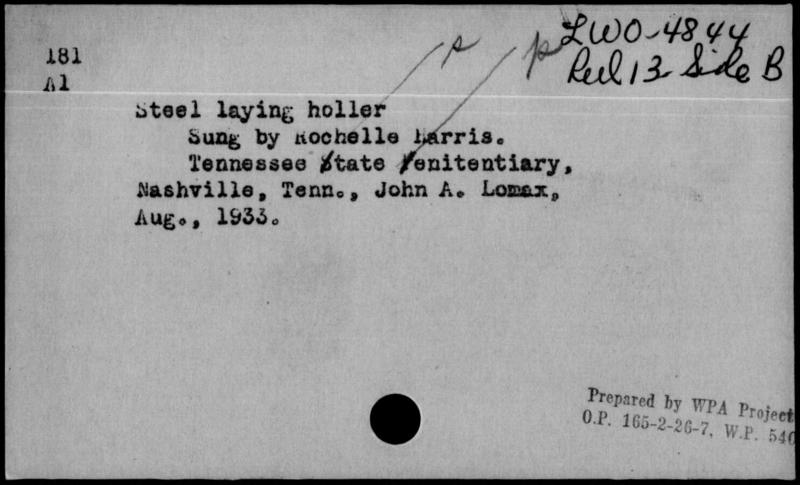

Yet even among field recordings, the Nashville material is little known compared to sessions in Louisiana and Texas. It does, however, include the signature sounds of hard labor, and showcases some female singers, like Rochelle Harris, on the “Steel Laying Holler.”

Decades before

The Prisonaires would top the charts with songs written in the state prison, it was a 500-pound recording machine that set the music to wax.

While the pops and crackles give away the age, Jackson says the

material is relevant — from an earlier era of prison overcrowding.

“We can see some people speaking to that from songs of the era,” Jackson says. “It might not be in the way that our president does, or our senators do, but it’s one voice.

Whatever happens to the medieval-looking prison, Jackson says it still deserves study.

“I’m not saying it necessarily it should be kept. Do we need a prison museum of that size? I don’t know,” he said. “But for me, it’s of interest because of its historical significance.”