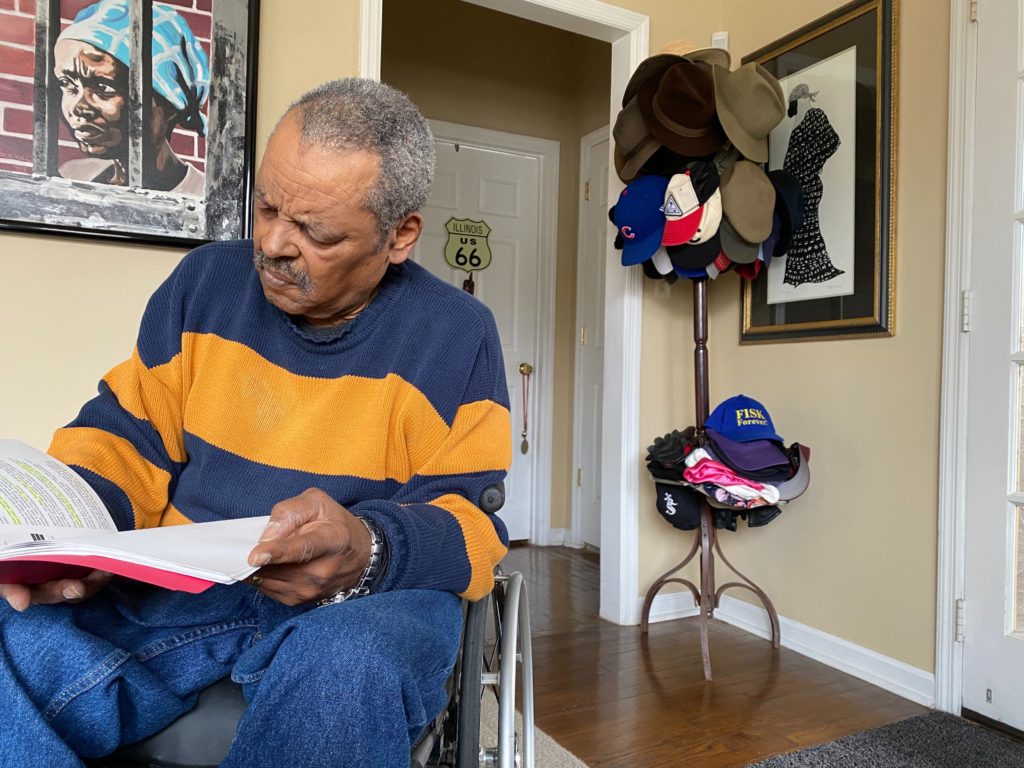

Walter Searcy has been pushing for changes at the Nashville police department for half a century. And he’s been closely following the case of Andrew Delke.

Delke resigned as a police officer and accepted a plea deal last week, just days before he was supposed to stand trial. I spoke with Searcy shortly after the hearing about how little has changed in his decades of activism.

Back in 1973, Walter Searcy protested the shooting of another young Black man by a white rookie police officer. In that case, the officer was charged with manslaughter — the same crime Andrew Delke pleaded guilty to.

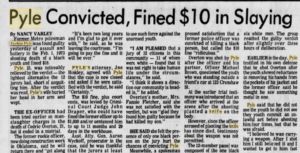

Courtesy Tennessean via Newspapers.com

Courtesy Tennessean via Newspapers.com A clipping of a Tennessean article from the 1970s about the case of Jackie Pyle, the only other Nashville police officer charged with homicide for killing someone. He was ultimately convicted on lesser charges and fined $10.

That case ended in a mistrial, and the officer was ultimately convicted of less serious charges. He was fined only $10. Like Delke, he faced the minimum penalty for his crimes.

Nearly 50 years have passed, and yet the outcome is so similar. I ask Searcy how he feels about that. He chuckles on the other end of the phone line.

“So similar. So similar. So similar,” he says, pausing each time he repeats it. “It just again demonstrates, as much progress as we like to think that we’ve made, there are things that make the progress seem anomalous and that the old norms just continue to persist.”

Searcy says officers are essentially allowed to carry out the death penalty, without a charge or a trial. And that those killed by police don’t get the presumption of innocence that’s supposed to be guaranteed in our justice system. Officers can decide in a split second whether someone should live or die.

“And that’s a frightening proposition,” he says. “And that’s why so many of our parents, if not the overwhelming majority, have to give their children the instructions.”

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsA child holds a sign that reads “When do I go from cute to dangerous” at a protest in downtown Nashville in the summer of 2020.

Searcy is talking about the instructions many Black children receive about how to avoid dangerous interactions with police. He says parents might even warn their kids not to drive at all in certain situations or times of day, just to be safe.

“If you keep me talking about it, you know, I just get even more depressed,” Searcy says. Not in the clinical sense, he says. “But it does piss me off. Let me say that.”

Searcy has spent more than 50 years protesting racial discrimination and police violence in Nashville. And it’s been hard for him to see officers shoot one person after the next and then be cleared of wrongdoing.

In the months leading up to the first murder trial of a Nashville officer, police shot five people. Those incidents are still under investigation. But the department has defended officers’ actions each time.

I ask Searcy what changes he would like to see in how the police department trains its officers, to avoid the cycle of shootings he’s witnessed time and again over the years.

“There’s no reasonable basis for the continued misconceptions on the street by police of what they’re facing,” he says. “The 14-year-old who looks to the policeman like a 24-year-old.”

Searcy says training needs to teach recruits to see everyone as a person first.

“If that’s not what we lead with but instead we lead with demonizing the perp and the other names we ascribe to criminal actors, we’re going to continue to have these problems,” he says. “And for those responsible for the training not to recognize that just simply perpetuates it.”

I bring up the term “implicit bias.” Many departments, including Nashville’s, have adopted training to help officers identify the unconscious thoughts we all have about people of different races and backgrounds. These classes have been touted as a tool to prevent police violence against Black people.

But I ask Searcy if he thinks it’s possible for white officers to unlearn the racial biases that even the most well-intentioned can’t avoid. And he says it’ll take more than implicit bias courses to solve the problem.

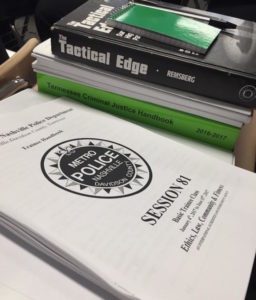

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNUntil recently, on day one of training, every new recruit in the Nashville Police Academy was issued a stack of reading materials. Right on the top is Tactical Edge, a textbook dedicated to high risk patrol.

“These things are occurring, and they are not random. They are just simply not random,” Searcy says. “They are a function of the training. And I can recall the manual that was being used until late in Steve Anderson’s tenure.”

Under former chief Anderson, the book, called “Tactical Edge,” remained part of the curriculum when Delke went through the academy. It taught officers to do whatever it takes to survive. And it also included dehumanizing language about people of color and public school students.

The department stopped using the book after WPLN News reported on it in 2017. A training instructor said at the time he didn’t believe the book was “controversial” but said the academy wasn’t teaching the sections identified by WPLN News.

“We’ve gotten rid of the manual, supposedly,” Searcy says. “But we haven’t moved far beyond those practices.”

So, I ask Searcy why he thinks both sides agreed to this deal, if he sees it as such a small step toward better policing. He says it would have been tough for the prosecution to get a conviction.

But what about Delke? I ask: Do you feel like this is a win for the defense?

“In the pantheon of things, I think it’s probably a win for no one,” Searcy says. “I mean Delke, he’s a young guy. And you know, he’s going to be a convicted felon, and he’s going to serve some time. So he’s not what he started out to be.”

Plus, Searcy says the victim’s loved ones and many in the community won’t be satisfied, either. With this plea deal, he says, no one is going home without some loss.

Samantha Max is WPLN’s criminal justice reporter and host of the Deadly Force podcast. You can find that series and all of her reporting on this case at wpln.org.

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.