Plans for the upcoming semester have been changing by the week for Middle Tennessee school districts. And now that in-person classes are imminent for many districts, teachers are facing their concerns about the coronavirus. And some of them are giving up their jobs.

“Right up until two and a half weeks ago, I was all set to start the new year,” says Jake Wilson, who spent this week cleaning out his classroom at Ellis Middle School in Hendersonville.

He says he spent the summer reading the books and writings he was going to assign his eighth grade English class, including Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

But then a couple of weeks ago, when Sumner County Schools decided they would not require teachers or students to wear masks, Wilson and his wife started thinking the district wasn’t taking the pandemic seriously enough. And they have a two-and-a-half-year-old with asthma.

So this week, Wilson left his 15-year teaching career to be a stay-at-home dad for a while.

“I can’t imagine not looking out at a class of 13 and 14-year-olds in two weeks. But I also can’t imagine getting my kid sick and seeing him in the hospital, and that being my fault,” he says. “So while it was a hard decision, it also wasn’t a hard decision at all.”

Wilson says two of his colleagues retired early because of health concerns. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that one-in-four teachers, roughly 1.5 million nationwide, are considered at-risk of complications from COVID-19.

Navigating Protocols

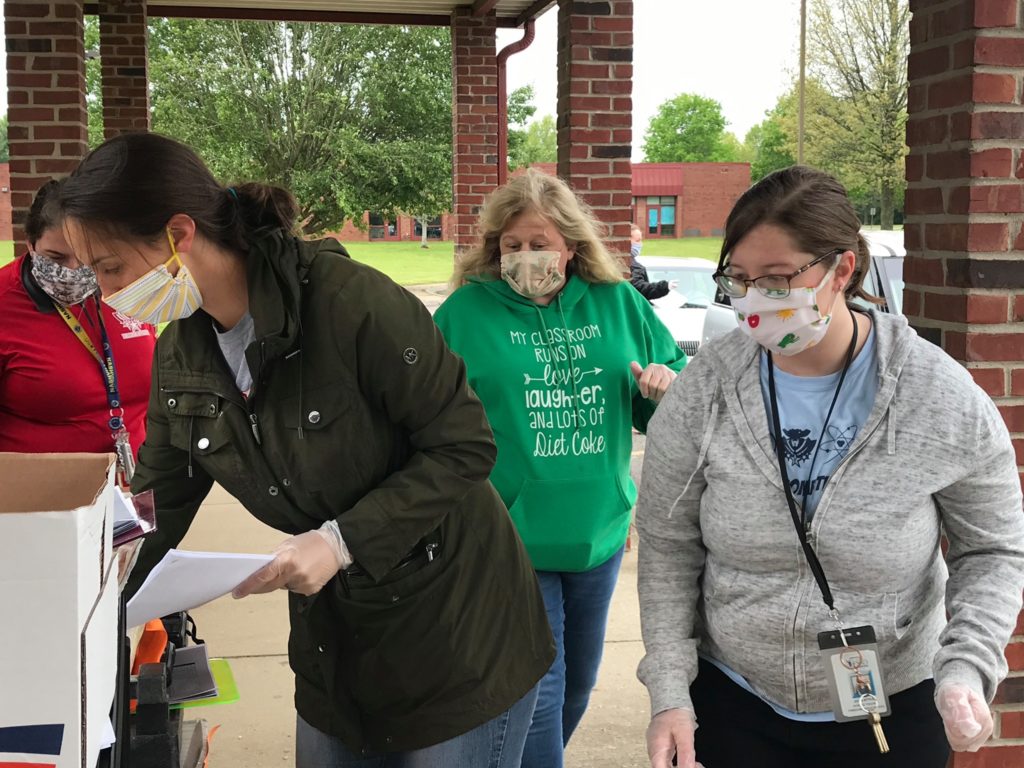

Middle Tennessee school districts — including Rutherford and Metro Nashville — say they’re not having to fill more positions than usual. But that could change once teachers get back in front of students. It did for Amanda Strawn.

She’s a pre-k teaching assistant in Franklin who returned to work in May. Then her classroom got its first confirmed case of coronavirus at the end of June.

The student showed up with a fever and was sent home. But it took a few days to get tested and two weeks for test results to show it was indeed COVID-19 — all while the student’s siblings kept coming.

“We needed to let all the parents know right away. We needed to let all the employees know right away,” she says “the whole hallway should have been shut down for two weeks.”

Franklin Special School District’s nursing coordinator, Amy Fisher, says she would have done more contact tracing if she’d been notified sooner. But the 14-day contagious period had already passed.

The school did send a letter home to classmates, but not in the siblings’ classes. And in Strawn’s view, the message to parents downplayed the risks.

“We as a society are not going to get through this pandemic if we’re not honest with each other. We’re just not,” she says.

Strawn took a day off, then decided to give up her job last Wednesday. She says having a policy to protect students and teachers is one thing. But following that policy will be the hard part.

Principals in Franklin Special have been given leeway to modify duties for teachers who are concerned about their health, Fisher says. “They’re doing all we’re able to for those folks,” she says.

“But we are committed to educating everybody on protocols so we can provide the safest environment possible. I can tell you we will be doing everything we can.”