Oceans are really stressed right now.

In July, 44% of Earth’s oceans were experiencing marine heat waves. That figure could increase to half in September and October, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and that comes with risks even for inland states like Tennessee.

The Gulf of Mexico recently reached water temperatures of over 90 degrees. In Florida, where the ocean possibly topped 101 degrees, the warm water is a major threat to coral reefs, which have been expelling their algae and “bleaching” white with the prolonged heat. It may result in a mass coral die-off.

“The era of global boiling has arrived,” UN Secretary António Guterres said last month.

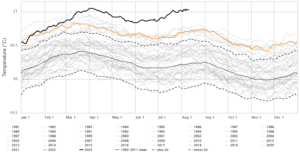

Courtesy Climate Reanalyzer, University of Maine

Courtesy Climate Reanalyzer, University of Maine The black line represents the daily average sea surface temperature in 2023.

Oceans absorb heat — but release it

The oceans have absorbed about 90% of the heat from greenhouse gas emissions, primarily caused by fossil fuel burning, deforestation and mass production of food and materials.

But this heat does not disappear, and it does not just affect marine life.

Warmer water in the oceans raises sea levels, melts ice sheets and directly reheats the atmosphere, sometimes contributing to terrestrial heat waves. Ocean heat also provides fuel for storms.

El Niño versus climate change

This year, Earth faces another El Niño, a climate pattern that happens when surface water in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean becomes warmer. It can cause climate impacts worldwide and significantly raise global temperatures.

El Niño affects weather differently across the globe. Some places get extra rain while other locations are more likely to face drought. In the Atlantic, there is usually less hurricane activity — but the record-warm sea surface temperatures may counterbalance any possible storm suppression.

Caroline Eggers WPLN News

Caroline Eggers WPLN NewsThe National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has doubled its forecast for an above-normal hurricane season since May due to record-warm sea surface temperatures.

On Thursday, NOAA increased the likelihood of an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season to 60%, forecasting between 14 and 21 named storms.

Hurricanes and tropical cyclones are driven by ocean heat. Storms usually form near the equator and then travel toward the closest pole.

‘All the way into Tennessee”

Tennessee faces risks from tropical storms. When formed in the Gulf of Mexico, or even the Atlantic, rain and sometimes wind can move across non-coastal states as tropical storms travel north along the coast.

“When we have really strong storms, there’s a higher likelihood that those impacts could reach further inland,” said assistant state climatologist Wil Tollefson. “So if we get a fast-moving hurricane … it can keep that tropical storm strength all the way into Tennessee.”

But slower storms, which are becoming more common in the Atlantic, are also a significant risk. A storm crawling up the coast has more time to drop rain as it passes Tennessee, especially in the eastern portion of the state.

Either way, when a tropical storm forms this year, it could be worsened by the excess ocean heat.

“When we have overall warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures, that just means those storms have more energy to work with,” Tollefson said.

Seabirds are threatened by warming oceans. The laughing gull, in the bottom right, is a common seabird along the Atlantic coast.

Mass die-offs of aquatic creatures

Warmer oceans can also threaten marine life, disrupting fisheries while also sending cascades of effects throughout the aquatic food chain.

Oceanic ecosystems depend on the natural circulation of water. Basically, winds blowing across the ocean push water, and water rises from beneath the surface to replace that water. Colder, nutrient-rich water “upwells” from deeper waters and fertilizes phytoplankton, which then feed zooplankton. When the surface is hot, however, the top layer of water can act as a warm barrier against cold waters below. That disrupts the cycle, causing some organisms to migrate to other waters.

There is another problem. As the oceans absorb greenhouse gas emissions, oxygen levels plummet and water acidifies.

Over time, ocean heating could cause a mass extinction of marine species.