The first thing to understand is, Islam is not the only religion middle schoolers learn about.

That’s immediately clear in Nick Rossi’s seventh grade social studies class.

“So, what religions total, have we discussed this year?” he asks.

It turns out, students at Antioch’s Apollo Middle School have covered seven different faith groups — just since August.

“Gary, give me another one,” Rossi implores.

“African!”

“African religions. Yes,” says Rossi.

Also, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Judaism. Plus, Confucianism and Daoism.

Now that state lawmakers are back at the capitol, they’ll soon deal with the dizzying debate over Islam. It has been rocking school districts around the state.

Activists and concerned parents worry middle school students are being “indoctrinated” with a sanitized version of Islam. In reaction, one legislative proposal would even restrict discussion of religion until the end of high school.

But in this Nashville classroom, religion — all religions — has been woven into the fabric of instruction. And the state’s controversial social studies standards are only part of the reason.

“Every single unit that we do has a religion standard,” says Rossi. “So, the state wants you to know it. Not only that, I want you to know it. Because in our community, we have people that belong to basically every religion that we’re studying.”

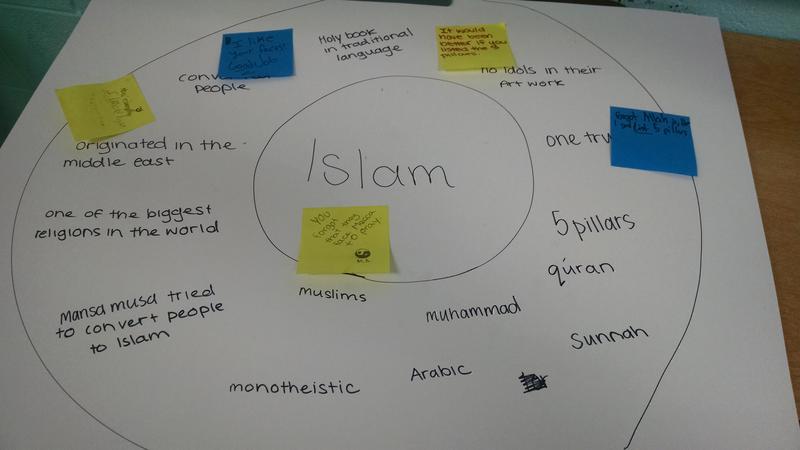

Rossi breaks the students into small groups and gives each a different religion. They have 20 minutes to write everything they’ve learned on a blank poster board: founding figures, places of origin, common practices and basic beliefs.

Two groups fight for the two they’re least familiar with. Rossi likes their enthusiasm.

“Yeah, [a] little competition for Confucianism and Daoism, wanting to do the more difficult ones. I think maybe they’re trying to prove themselves — to you or to me, I’m not sure — but I’m into it.”

Focus on Islam

Since the start of the school year, these very lessons have been at the center of controversy, and opposition focuses squarely on Islam. Foes say lessons are designed to downplay Islam’s negatives and present it in a favorable light.

They want textbooks returned to their publishers and Tennessee’s social studies standards rewritten.

Julie Mauck has children in the Williamson County school system, including twins in seventh grade. Last month, she attended a forum in Cool Springs organized by opponents of the state’s social studies standards.

“It just whitewashes the history,” she says. “There’s barely a mention of jihad. There’s barely a mention — or I don’t think there is — a mention of caliphate and what their objective is.”

Mauck believes schools aren’t the place for 12- and 13-year-olds to learn about faith.

“I mean, being a Christian, I don’t necessarily want the public school system teaching my children their version of Christianity.”

Some lawmakers are saying the same thing. Columbia Republican Sheila Butt is proposing a bill that would delay instruction on religion until at least the 10th grade — an age when she believes children are ready to start exploring other faiths.

“Students start thinking a whole lot more about what their peers think, about ‘Hey, there is more than just what my parents are teaching me’,” she says. “But in the meantime, let’s give parents the opportunity to teach their children in their home what they believe and teach them at their age what they believe.”

Meanwhile, state education officials have agreed to a yearlong review of the social studies standards.

But Vicki Kirk, the deputy education commissioner, says it’d be a mistake to write religion out of middle school curriculum. Students, she says, can’t understand history or the world today without knowing about people’s beliefs.

“We have so many students in Tennessee that rarely go outside the borders of their hometown,” she says. “Let’s say I wanted to be a missionary. It would be pretty important for me to know a little bit about other cultures if I was going to go live in one.”

Nick Rossi’s students show they’ve learned more than “a little bit.” On the poster of Islam, they note followers believe in a single God and their holy book, the Quran, should be written in Arabic. They say it’s one of the world’s biggest religions, and that one of its most powerful early figures, the African king Mansa Musa, tried to convert his entire nation.

Rossi urges them to keep going.

“It would have been better if you listed the Five Pillars,” he says. “But I think we know the Five Pillars. Let’s see if we can get them. Five Pillars of Islam. Go.”

“Prayer, faith, pilgrimage,” his students call out.

“Prayer, faith, pilgrimage. What are the other two?” Rossi presses.

After some discussion his students come up with the correct answers — fasting and charity.

These lessons won’t be Mr. Rossi’s last on religion. Pretty soon, the class will move on to the Protestant Reformation, the beliefs of Native Americans and Japan’s Shinto faith.

It’s all part of passing seventh grade history in Tennessee.

At least for the time being.